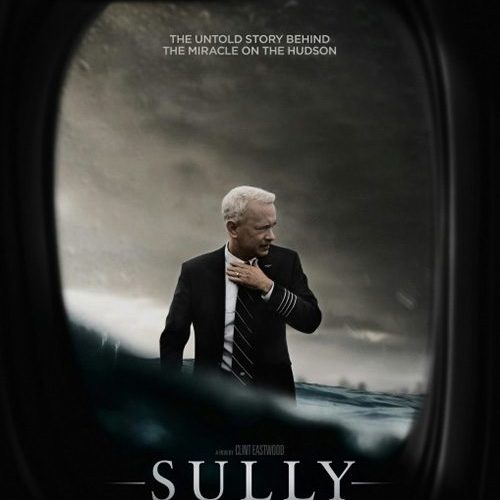

You know the inciting incident because it is not quite like any in recorded human history, and you could stare at the foreboding, nigh-apocalyptic poster to no end before being fooled into anticipating a conclusion that’s anything but triumphant — the sort of victory we can find comfort in almost expressly because it’s so expected. So there’s the question of why and how Chesley “Sully” Sullenberger’s “Miracle on the Hudson,” a three-minute-long event, necessitates the big-budget cinematic treatment, other than, of course, “it’s cinematic!” (A plane sitting between two cities is a great image, no matter the danger endured by ordinary people so we could get it.) Clint Eastwood never directs pictures with so simple a follow-trough, and, sure, Tom Hanks is always a welcome presence. Thus there is Sully, just such a big-budget film centered on the scariest few minutes anybody ever came away from almost entirely unharmed.

Even though he’s proven ample at staging set pieces, a plane crash doesn’t feel just the fit for Eastwood’s more relaxed, careful rhythms, and his adjustment announces itself with the film’s in-media-res start. But right away the movie isn’t what you expect: Sullenberger’s landing has already happened by the time WB’s logo appears; now come the fireball nightmares and doubt-filled deliberations, in which a set of investigators respectfully inquire if the Hudson River was even a necessary target when two airports were within his near or immediate vicinity. Eastwood makes awfully clear that his hero’s in a tough place: a sad shower here, a bit of treacly score there, a slow push-in in case those don’t settle the matter, and great narrative emphasis on his frayed marital life with a woman (Laura Linney) who, even in flashback, is limited to the role of concerned person at the other end of a phone line. If the movie doesn’t know what to do with those many moments — and they are bad in their to-the-point dialogue exchanges and plodding musical cues, redeemed only by a director and DP (regular collaborator Tom Stern) who can at least visually illustrate the huge gulf between domestic and traveling life — it seems to entirely be the result of being deeply fascinated with its key figure.

Whether or not Sullenberger was a great man, one who’s “simply” extremely good at his job, or, more ambiguously, one who was blessed by something divine on January 15, 2009 is a question Sully retracts from just as quickly as it’ll make an approach. It’s here the casting of Hanks — one of the few noble-seeming movie heroes we have because he, against most reason, resonates as a regular guy — matter most. He’s too recognizable to ever not be Tom Hanks, but his Sullenberger is one of humble presence and basic decency, and his character’s PTSD — one of a few things tying this particular based-on-true-events film to Eastwood’s previous picture, American Sniper — creates a unique fit: a familiar onscreen presence has ways of turning into something altogether different, something off, with an actor’s slight change in gait, glance, and tone of voice.

The strengths of performance and its peculiar emphases aside, it goes without saying that everything comes back to the crash, which Sully gives us, more or less from beginning to end, three times over. Such a plurality initially strikes one as a convenient narrative and formal device: extend the movie’s runtime while ratcheting up excitement time and again if meetings begin feeling a little stale. It is wiser than this. The angles taken — Sullenberger and his First Officer, Jeffrey Skiles (a hard-headed, impressively mustachioed Aaron Eckhart); members in LaGuardia’s control booth; and the passengers themselves (including a rather lame stab at pathos in the form of two men and their elderly father who just made their flight) — bear distinct ways of emphasizing this accomplishment in its strengths and oddities without ever really treading familiar ground. These clarifications do not elide mystery. No matter how much we walk through the process, and especially how many times we experience it, the landing remains inexplicable — hard work or intervention? If intervention, for what, exactly?

Notwithstanding flirtations, including a pointed fortune cookie message, Sully ultimately leaves itself to practicalities. The conflict of whether or not Sullenberger should have landed as he did will be solved, and while that answer is, again, an inevitability, there’s too much straightforward pleasure in his cunning perception and the deserved feel-good ending it leads us towards to consider that a fault. The film isn’t afraid of allowing darkness to seep in — a PTSD-fueled waking nightmare of his crashing into midtown plays close to the psychological process of projecting thoughts onto the real world — but, structural trickery aside, which is itself really an accomplishment of scribe Todd Komarnicki, we’re witness to one of Eastwood’s more relaxed formal turns in some time. It basks in the rightness of those who work hard to get a proper result, simultaneously disinterested in reinventing the wheel and still finding some new ways to spin it.

Sully opens on Friday, September 9.