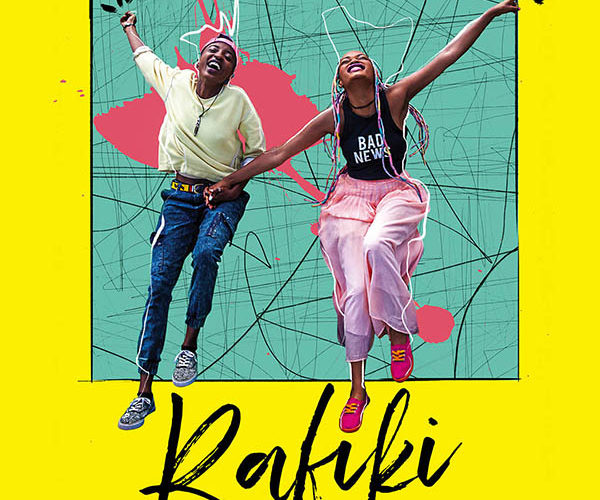

Some will dismiss Wanuri Kahiu’s Rafiki as derivative simply because they refuse to see what makes it so special. They’ll mention its Romeo and Juliet parallel as far as having the children of opposing political candidates fall in love. They’ll compare it to generic love stories—and generic gay love stories—because that’s what it is at its core. And when the subject of prejudice and violence towards these young lovers arises, they won’t shy from deeming it already treaded territory. What such reductive takes ignore, however, is that this isn’t just a gay love story between two women who should be diametrically opposed to one another due to their fathers’ ambitions. The fact it takes place and was shot in Nairobi, Kenya makes it so much more.

This truth isn’t reliant on the political ramifications spawned upon its Cannes release either—although it surely helps shine a light on its importance. After getting showered with international praise in France, the Kenyan government publicly denounced the film because of its LGBT theme possessing a positive agenda despite homosexuality being illegal there with a potential sentence of fourteen years if caught. So officials would of course what to censor its message of free love and understanding to keep their population under foot. The courts eventually allowed Rafiki to be screened to sold-out audiences in multiple Kenyan cities (for seven days only), but it unsurprisingly wasn’t chosen to represent the country at the Oscars. The impact, however, has probably been as great as if it had won.

What makes Kahiu’s film essential beyond that moral and artistic victory is its ability to instill hope within a hopeless situation. From the colorful opening credits to the stellar soundtrack to the beautiful cinematography putting Kenya’s vibrancy on display, she’s given the world a depiction of romance (same sex or not) that’s just as cute, relatable, and potent as those Americans see every month at their local theaters. This is a contemporary slice of life drama that provides its central characters the agency with which to choose the existence they desire regardless of what cultural, societal, or familial traditions demand. These women aren’t merely bucking against the religious norms of gendered relationships, but the patriarchy at-large. They are here to be more than wives and mothers.

Kena (Samantha Mugatsia) wants to make her parents (Nini Wacera’s Mercy and Jimmy Gathu’s John Mwaura) proud by becoming a nurse if her grades are high enough. She wants this self-sufficient trajectory because she’s seen what happens when marriages built upon the promise of stability rather than love ultimately fail. By contrast, Ziki (Sheila Munyiva) strives to escape her parents’ (Patricia Amira’s Rose and Dennis Musyoka’s Peter) long shadow. She has money and thus the imagination to believe she can leave Kenya behind and travel to places that would accept her progressive sensibilities more than this conservative hometown. Ziki hopes leaving can bring her happiness away from their oppressive surroundings while Kena seeks to find joy despite them. Meeting each other couldn’t have happened at a better moment.

Why? Because Kena gives Ziki a reason to stay while the latter gives the former the support to make her dreams even bigger than they already were. Unfortunately, however, lies the realization that this might also be the worst time to meet considering the scrutiny placed upon them as daughters of two prominent men battling for public approval. It’s this sort of duality that permeates the entirety of Kahiu and Jenna Cato Bass’ script (adapted from Monica Arac de Nyeko’s short story “Jambula Tree”). The most obvious example is of course Kena’s uncertainty forcing her to keep a foot in two worlds: the one where she will do anything for Ziki and the one under the wing of Blacksta (Neville Misati) and their homophobic friend Waireri (Charlie Karumi).

There’s also Mercy approving of her child’s friendship with her ex-husband’s rival because she believes Ziki will be a positive influence coming from a well-to-do household (and some petty vengeance is also surely a factor) and John’s disapproval because that camaraderie makes it seem like his daughter isn’t on his side. What you might not notice at first is that this division is due to their expectations for Kena. Her mother wants her to be suitable for a wealthy doctor (despite being able to become a doctor herself) and thus excise herself from the likes of Blacksta and other boys going nowhere. Her father wants to assist his community and knows he can’t without her support. If not for that the election, he’d be ecstatic Kena was happy.

It’s these underlying motivations that rise to the surface once Kena and Ziki’s tryst is inevitably discovered. Mama Atim (Muthoni Gathecha) and her own daughter Nduta (Nice Githinji) steal many scenes as the town gossips injecting themselves in everyone’s lives by sowing the seeds of drama and chaos to ensure it. Which parent if either will still see his/her child as a person and which a vessel controlled by demons? Who in the town if anyone will come to Kena and Ziki’s rescue when the mob forms to make an example of them as unholy abominations to laugh at and beat? Nothing is more powerful than love when presented under terms you preconceive as objective truth. Only when that façade disappears do you witness whose love was real.

That revelation is where Rafiki shines because it’s not just the idyllic romance we see at the start. We need Kena and Ziki’s love to blossom in this sweetly innocent way to know it’s real enough to survive the struggle to come. So we smile when they smile, dance, and hold hands. And we go silent when Ziki’s overzealousness risks outing them just as Kena’s pragmatic rejection of such boldness risks breaking them apart. The complexity of this point becomes crucial to the whole because these women can’t just pack up and leave when doing so would entail poverty, abuse, and worse. There are consequences to their actions and they must weigh whether their happiness is worth watching the person they love get destroyed. It’s a bittersweet tragedy.

The hopefulness that forms from this turmoil can’t be discounted, though. No matter how dark things get, there remain glimmers of hope even if via knowingly silent support rather than outspoken action. And if Kena and Ziki’s union does break, who they’ve become as a result of that love can’t disappear. Both Mugatsia and Munyiva deliver unforgettable performances—opposites attracting in the most relatable and promising ways. Their socio-economic status dictates much of their attitude and cognizance towards the dangers they face and yet it all washes away when they’re together, lost in each other’s arms. That the world could ever reject what it is they share is the real offense and why having Kenyans tell this story onscreen is crucial to dismantling indoctrination with pure, resonant humanity.

Rafiki opens in limited release on April 19.