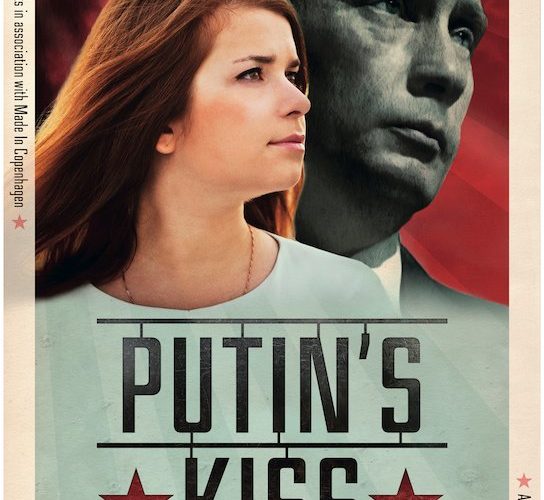

Putin’s Kiss, the Sundance Festival-approved documentary on the modern state of Russia, shares similarities with its subject. Director Lise Birk Pedersen‘s debut feature-length film is informative and interesting but, like the regime it focuses on, isn’t exactly what it says it is. Much like the criticisms that various talking heads level at Vladamir Putin’s top-down authoritarian stronghold over the country’s “democracy,” this film purports to be about a young girl’s journey towards enlightenment, which is the weakest of its many narrative threads.

Masha Drokova never knew communism. Now in college, she grew up with relative prosperity in a small town just outside of Moscow, now big and bright and littered with billboards touting expensive foreign cars, cell phones, and other hallmarks of consumer-based capitalism. If only the Soviet kids who weren’t allowed to buy denim jeans could see what their country has turned in to. Drokova is a modern girl with modern issues who is also not like the rest of population at all. She’s a high-ranking member of Nashi, a government-backed youth group that aims to mobilize young people to build a stronger Russia. Something possible only through unwavering support of Putin and the suppression of the country’s “villains.”

Nashi holds an annual camp to gather the children from across the country together and lead in a wonderful jamboree that is really a thinly-veiled indoctrination course. The introduction to from the governmental liaison Anton Smirnov promises that in “…eight days, you’ll be different a different person,” music to the ears of most teenagers. While the group maintains a docile public front — through delightful, TV-friendly folk like our Masha — there is a hard-lined edge to the group that is beginning to throw its weight around. It’s an allegation leveled by Oleg Kashin, our voice over guide through the film, and a member of a small cabal of independent journalists and bloggers who attempt to expose the group for what it is, often to personally damaging results.

In Masha and Kashin we have our two leads, both on opposite sides of the same Nashi-minted coin. Masha is happily a cog in the machine, grateful for all it’s given her: an apartment in Moscow, a Mazda, a college education, and a job as a journalist on her own television show, all thanks to Nashi. She doesn’t have the wool pulled over her eyes; she has the finest silk draped over her while she gets a Swedish massage. With this kind of comfort and opportunity, who would want to resist?

But soon the journalism bug grabs hold of Masha. After sharing the stage on a televised roundtable debate show, Kashin begins to get in Masha’s ear about the true motivations of Nashi. Soon enough, Masha warms up to these opposition leaders as fellow journalists and friends. How could people this nice be so bad? But, piece by piece, brick by brick, Kashin and company start to chip away at her devout allegiance to Nashi and starts to question its policies and motivations. One singular event brings Masha to a crossroads: does she continue to support the group that has essentially raised her, or does she break out on her own?

For dramatic reasons, the ideal would be to merge our two leads into one compelling character who leads a clean, interesting narrative. We’d have the indoctrinated girl — the one who kissed Putin as a teen, who has influence through television, a staunch supporter of the regime — who gains clarity and turns against her former masters, setting out on her own to find the real truth behind the machine she was once a part of. But that’s not reality, and that’s not how this film pays off, though it feels as if it wants to steer us in that direction when the rebel journalist is our guide and essentially only our trusted ally.

This is a movie whose look on the culture surrounding our characters is seemingly more interesting than the story it is trying to tell. Pederson gets pretty remarkable access, most specifically in two Nashi operations. They claim to be “anti-fascist” but large murals of Putin and Smirnov line the walls of the introductory camp, symbolically watching over the proceedings with great diligence.

The other revealing event is National Unity Day, where 30,000 Nashi members are bussed into Moscow to demonstrate not their allegiance to Russia, but the symbolic destruction of hundreds of Her “enemies,” whose names and crimes are listed on placards as the youths march through the streets, before getting thrown on the ground and trampled on in disgust. All the while, the apparently removed Smirnov stands aside, busily fixing every minor detail amongst the minions he has cultivated.

These are the kinds of moments that tell the entire story of Russia through metaphor; they say one thing but are another entirely, to the chagrin of those who care to look for it. Unfortunately for the film, neither of those sections feature our protagonists. Putin’s Kiss is more interesting than compelling; and luckily it’s a rather interesting subject overall. We didn’t need a narrative through line to find a story here; Russia is the story. Instead, we’re left with a movie that tries to make me care about the girl who kissed Putin while I care much more about the guy who was kissed.

Putin’s Kiss opens in limited release on February 17th.