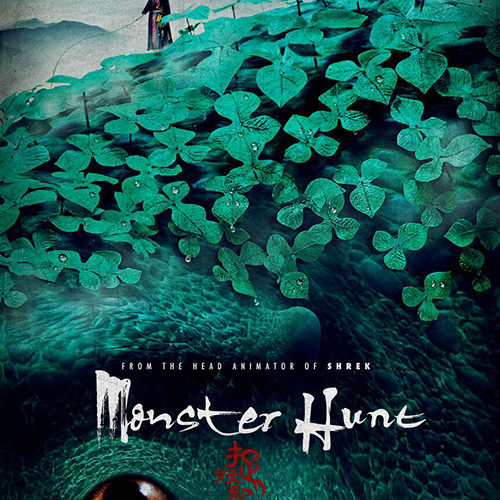

Even if Monster Hunt were billed in America with “from Raman Hui, the supervising animator of everyone’s favorite DreamWorks player, the Gingerbread Man, and co-director of Shrek the Third, comes a magical adventure of man and beast” on the posters, it wouldn’t be enough. But that’s okay, because Hui didn’t make it for American audiences. Instead, it stemmed from a desire back in 2005 to make an animated film in China after spending so much time with Steven Spielberg‘s company learning the ropes. A decade later and the finished live-action-animated hybrid became the nation’s highest-grossing film ever (since beaten by Stephen Chow‘s The Mermaid). Not even the boast of this acclaim could make it a winner stateside, though. It’s simply too weird for western audiences.

That doesn’t mean it’s bad or indecipherable. Hui utilizes many of the same themes from the Shrek series with the assistance of screenwriter Alan Yuen and further inspiration courtesy of the 4th-century-B.C. book Classic of Mountains and Seas. Rather than ogres discovering their place alongside a fearfully skeptical human population, this Chinese tale delivers a baseline of monster races and species similar to the vast imaginative lineages crafted by J.R.R. Tolkien for his Lord of the Rings saga. Mix the parable notion of inclusiveness and respect to those different from you with wuxia, slapstick, reversed gender roles, and cute (yet potentially menacing) rubbery blobs of character creation resembling many mobile video-game aesthetics currently on-sale, and you can begin to see what I mean by “weird.”

Just as international audiences struggle with pop-culture references and western tropes littered within our family fare, we in turn find it difficult to look below surface perplexities in theirs. I don’t know if a universal expository history for monsters exists in Chinese tradition, wherein everyone automatically understands that mirrors freak them out and magical stickers freeze them, but I wasn’t going to let the learning curve deter my enjoyment. If those really are the rules, great; if not, projecting simplistic meaning worked well enough for me to get through the odd dynamic built between humans, monsters, and hunters. So I’m going to pretend I was correct. After all, how one side defeats, immobilizes, or befriends the other is inconsequential. The capacity to do so is what matters.

And that capacity stems from our hero, Tianyin Song. (While originally played by Kai Ko, Hui had to reshoot the whole movie with Boran Jing because China wouldn’t let a convicted felon — Ko was arrested on drug charges — headline a film). He’s a lame young man saddled with a leg brace and lack of confidence, despite constantly being told by his senile grandmother (Elaine Jin) that he was destined for greatness. “Was” because she no longer believes it and would rather search for her missing legendary Monster Hunter son than waste more time on the boy. In her absence, the responsibility of the village becomes Tianyan’s, and his first act is to invite in two monsters with a smile that literally tell him he’s their dinner.

In his defense, no one knows monsters are real anymore. A prologue of exposition and the pontificating of Monster Hunter Chief Ge Qianhu (Wallace Chung) explain how the worlds have been separated long enough for normal people to be oblivious — like our penchant for dragons. Luckily for Tianyan, a hunter-in-training also arrives at the village and she (Baihe Bai‘s Huo Xiaolan) can see through the intruders’ disguises. Suddenly, this unsuspecting restaurateur finds himself embroiled in a war of prejudice that’s been waging for millennia. The old queen of the monsters (whose royal family was murdered by the new king) appears, giving Tianyan her baby for protection as she perishes. And by “give,” I mean impregnate. Yes, the “good” monsters’ salvation is a pregnant crippled man.

Still with me? If so, I applaud you and warn that Monster Hunt gets crazier. More hunters, like Wu Jiang‘s Luo Gang (a Level Four in comparison to Xiaolan’s Level Two), join the fun opposite gigantic beasts as cute as the little radish named Wuba, who eventually pops out of Tianyan. A desperate couple (Ni Yan‘s Luo Ying and Jianfeng Bao‘s Zheng Tao) seeking help conceiving their own child enter for pratfall humor and to steer us towards the big city’s five-star exotic cuisine able to cure any ailment. And a secret truce of cohabitation is revealed with the promise that peace can be had if only both sides stopped their feud. But as long as “bad” monsters keep eating humans, the “good” vegetarians don’t stand a chance.

I liked the comedy enough to see that kids will have fun. Certain moments become scary, but that’s a welcome result to let stakes be authentic. Some stretches are made emotionally sad, too, for added investment — right up to an ending reminiscent of every “love them and set them free” film since before Harry and the Hendersons. Not everything is especially kid-friendly, considering the sex jokes and unforgettably vampiric example of breast-feeding, but the tone remains over-the-top and cartoonish enough to distract regardless. That tone can make it rough for some adults, but that’s where the intensive wirework succeeds in delivering some well-choreographed action. Include the chaotic nature of retractable, swinging cages to catch the monsters and the cinematography is nothing if not exciting.

As for the animation: it’s good. It’s great when we’re just viewing quiet scenes of Tianyin and Xiaolan dealing with Wuba, but as soon as CGI and humans need to battle, any verisimilitude to scenes falls apart. But this is expected when your computer characters are so obviously not of this world. The filmmakers aren’t trying to frighten before the story even begins, and so the cuter, more cherub-like something is, the more out-of-place it seems. There’s a charm to this that makes Monster Hunt worth seeing if only for curiosity’s sake. And, with a blatant opening for sequels, this saga may get even stranger.

Monster Hunt is now in limited release.