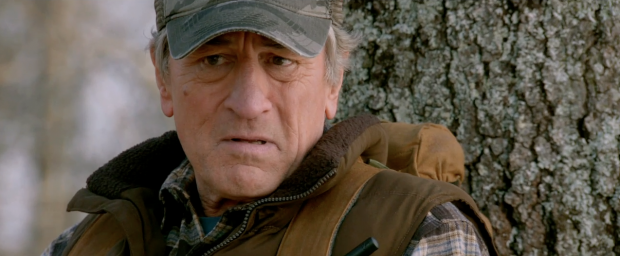

Killing Season is Redbox-level trash that gives two storied American actors—Robert De Niro, 69, and John Travolta, 59—their first-ever opportunity to share a movie screen. The movie’s screenplay, written by Evan Daugherty (Snow White and the Huntsman), places the two of them in the wilderness, where a game of brooding philosophizing and cat-and-mouse torture ensues. The movie’s director, Mark Steven Johnson, has a few expensive credits to his name (2003’s Daredevil, 2007’s Ghost Rider), so, at the very least, he knows how to film a scene without stumbling into focus problems or sound-clarity mishaps. For me (and, I suspect, for a lot of people that love movies), these ingredients add up to form something that has an inherent measure of entertainment: of all the one-sentence pitches I can imagine for films that have been released this year, few are as remarkable as, “Robert De Niro and John Travolta (sporting a thick, outrageous Serbian accent, no less) torture each other in the woods for a brisk 90 minutes.”

The production history of Killing Season is a hoot in its own right: Daugherty’s original script, which garnered Black List certification, was titled Shrapnel. Set in the 1970s, Shrapnel centered on the battle between an American World War II veteran and a former Nazi. At first, action-genre stalwart John McTiernan (Die Hard, Predator) emerged as the likeliest contender to direct—a development that would’ve marked his first behind-the-camera effort since 2003’s Basic (which starred Travolta). In due time, though, McTiernan stepped out, Johnson stepped in, and Daugherty’s screenplay shifted from a post-WWII mindset to a post-Bosnian War one. Among other things, this speaks to how removed Killing Season is from everyday society: assuming that much of the film’s dialogue and scene specifics are the same as they were in Shrapnel, it probably took Daugherty all of two or three afternoons to update the historical backdrop.

The grisly violence and battlefield flashbacks of Killing Season are its main issues: these moments are offensively moronic, as opposed to the rest of the film, which is mostly moronic in a this-is-awesome kind of a way. The opening prologue, in particular, is terrible: titles cards that could double as Wikipedia copy-and-pasting give us quick specifics of the battle in Bosnia, but it’s the careless violence (computer-generated corpses that look like they were added in four days ago, gunpoint executions shown with unsparing detail) that momentarily sours the mood. However, Travolta’s first dialogue scene, which brings the film to the present day, rekindles our faith: donning a facial-hair scheme and an accent that both defy classification, Travolta’s Emil Kovac, a brutal ex-Serb-soldier from the Scorpion group, finally gets his wish when he receives a file (complete with awful Photoshop tinkering) containing the identity of the American soldier who nearly took his life.

That soldier, of course, is De Niro’s Benjamin Ford, and Killing Season continues to shine in its opening-credits depiction of Ford’s hermit-like daily existence. Maintaining neither a cell phone nor an e-mail address (he’s an old-timer!), Ford has retreated to an isolated cabin in the Appalachian Mountains, where he gets the occasional call from his estranged son (Milo Ventimiglia, who played Sylvester Stallone‘s son in 2006’s Rocky Balboa) attempting to ask for familial connection. The greatest joys of this sequence, though, are found in the stock details of Ford’s activities: he wakes up at 6 a.m. and does a bunch of push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups; he chops wood to maintain a nice fire; he creates makeshift, camouflage tents in the woods so he can take photographs of animals without scaring them away; and, at the end of the day, after finishing a home-cooked meal, he reads Hemingway and listens to Johnny Cash.

Predictably, there are glitches in Ford’s routine the next time he tries it: he runs out of painkillers for the shrapnel (there’s the original title again) in his leg, forcing him to take a trip into town in his Land Rover. Quickly, however, the car breaks down, and a peculiar-seeming stranger—you guessed it, Travolta’s Kovac—arrives out of the bushes to fix the car. Next thing you know, Ford is asking Kovac over for dinner, Kovac is whipping out some liquor, the two are sharing stories and remembrances, and we’re right back in Johnny Cash territory. Sarcasm aside, though, this is actually a compulsive watchable scene that consists of nothing more than these two actors “shooting the shit” for what seems like at least ten minutes. Like the rest of the movie’s best stretches, this one glides solely on its two leading men: if Johnson’s directing deserves any credit, it’s in the fact that he clearly knows to defer to his actors as often as possible.

The late-night male bonding can’t last forever, though, as Kovac must act out his initial plan: the next morning, he invites a reluctant Ford along for a hunting trip; within minutes, De Niro has a bow-and-arrow lodged into his calf. This is when the movie reaches its preferred pitch of watching Ford and Kovac taking turns torturing each other, with each spout of violence separated by a handful of lines about each character’s beliefs on war, God, religion, existence, violence, etc. The carnage here is occasionally a bit much—I’m not sure I needed to see De Niro pull the arrow out of his calf, then be forced to insert a string into the open wound, then be hung by that very string—but it’s also responsible for some of Killing Season‘s signature moments, like the scene in which De Niro waterboards Travolta with an improper concoction of iodized salt and freshly squeezed lemonade. (Johnson gives us a water-clogged point-of-view shot here.)

I’m afraid you’re on your own if you take a chance on Killing Season expecting a work of objective quality. This is not that kind of movie: this is something you watch because the sight of De Niro and Travolta beating each other to pieces and speaking third-rate dialogue as if it were world-altering profundity is a swifter and more enjoyable thing to do than, say, spend $18 and three hours of your time seeing a mediocre tentpole in muddled 3-D. The movie is pleasant enough to look at, too, even if there’s not much artistry in the images of Australian cinematographer Peter Menzies Jr.: it’s hard to ruin locations like this. (See William Friedkin‘s 2003 The Hunted for an example of a better-photographed movie working with similar wilderness landscapes.) Killing Season also has the wherewithal to present its gambits in moderation: some of the earliest encounters between the two actors may seem hard to top, but the movie saves its wacko invocations of religious imagery and confessional rituals for its concluding portions.

Killing Season hits theaters and VOD on July 12th.