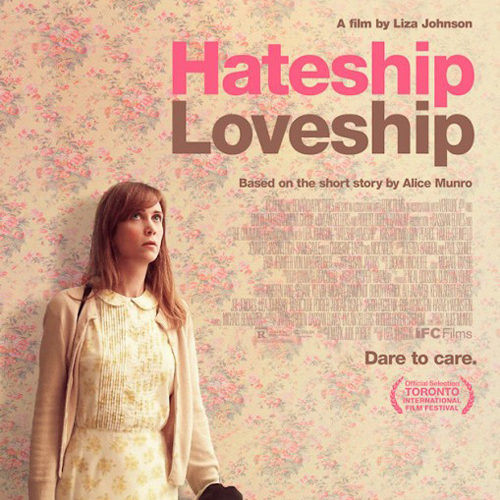

There is something appealingly ambiguous about the story at the heart of Hateship Loveship. It goes through the paces and hangs itself on the narrative framework of a romantic drama, and yet it leaves behind all of the various neat bows and long-winded speeches usually associated with the genre. It explores the kind of impossible situation you think you’d only find in a film, but allows the inherent flaws and brokenness of humanity to live and breath. This makes it a hard film to examine or convene a solid opinion on, but it also makes it one well worth seeing.

Of course for a film to survive narrative ambiguity — to not succumb to the usual doubts that plague a viewer after the lights have gone up — the characters have to be worth investing in and believing in. Luckily, the cast is game for the challenge, and even given the limited scope of time spent with some of the characters they are all imbued with a deep humanity.

The center of the film is Kristen Wiig playing Johanna Parry, a reserved and deeply anxious woman who has spent years as the caretaker of an aged woman who finally succumbs to her illness. From this job Johanna moves in with Mr. McCauley (Nick Nolte) and his granddaughter, Sabitha (Hailee Steinfeld) to help McCauley care for the Sabitha following the death of her mother.

Sabitha’s father Ken, played with the kind of grungy obliviousness out of which Guy Pearce could make a full-blown career, is an inveterate booze hound with a penchant for cocaine on top. Yet when a prank orchestrated by Sabitha and her “frenemy” leads Johanna to believe Ken has feelings for her, she defies logic and reason to pursue him.

The outline above may seem to be building towards a comedy of mistaken intentions and tearful revelations, but the film never ceases to subvert these expectations, allowing the characters to speak their minds and state openly all the things savvy audiences might shout at the screen during a lesser film. The conflict never devolves into a round of questions revolving around when or if people will be set straight. Instead, it comes from the realization that the healing that occurs after truth and feelings have been spoken aloud is more difficult than the speaking of the truths themselves.

Wiig makes Johanna, a character seemingly bred to be a kind of manic pixie dream girl or all-healing maid, into a woman fully composed of all the desire and intractability and drive of a flesh and blood human. She synthesizes the pain and introversion at the heart of comedy — her usual bread and butter — into a winning dramatic whole. Pearce never plays his addictions into melodrama, instead making them components of a man who is flawed perhaps beyond repair, but out of habit and need more than choice. Steinfeld likewise gives her character the shadings and undercurrents that sell the dramatic swings from wild confidence to morose uncertainty.

As directed by Liza Johnson (Return) the story unfolds in unpretentious directness, allowing silence to speak just as loud as the words spoken, and letting the changes in the characters and their surroundings mark the passage of time. She lets unmarked passages of time elapse, sacrificing slow evolution of plot for patient examination of shifted paradigms. The effect is jarring, like visiting family at the holidays after months of silence, but firmly places the viewer in the shoes of characters who drop out of one another’s lives both with and without reason and yet struggle to find understanding and forgiveness.

With its muted emotional beats and understated tone, I don’t doubt that Hateship Loveship may have trouble reaching some audiences. Catharsis and climax are supposed to exist in movies and leave the greatest mark on an audience, but real life is filled with broken silences and uncertain feints toward the future. Hateship Loveship understands that and, despite its seemingly canned plot, commits to delivering a glimpse into that truth spiced with the joy of optimism rather than the easy placebo of certainty.

Hateship Loveship is now in limited release and available on VOD.