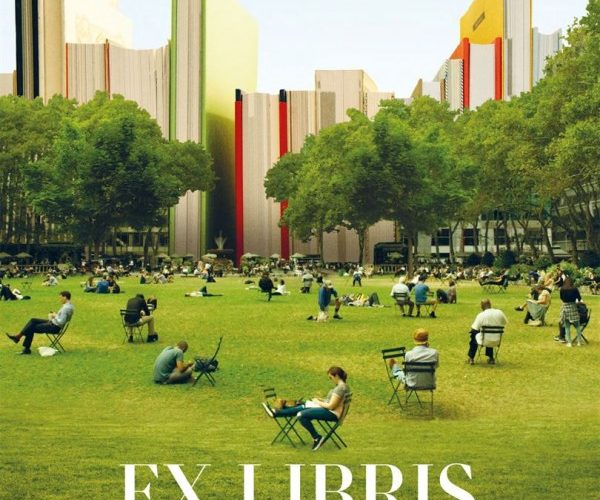

Frederick Wiseman’s films are often filled with moments that subtly and unexpectedly jolt viewers who think they know what they’re in for. In Ex Libris, in which he focuses on The New York Public Library, such a moment comes when Francine Houben, creative director of the firm selected to renovate the institution’s iconic Stephen A. Schwarzman building in midtown Manhattan, explains that libraries are not about books, or their storage, but about people. With this simple statement Houben encompasses the spirit of Wiseman’s generous, enlightening look at one of the most important organizations in the city, and as the film suggests, perhaps also an essential tool in preserving the American ideal of freedom and equality.

Even if it sounds like a platitude, the notion that knowledge frees the spirit has rarely been captured with the insightfulness Wiseman grants his film. He removes the romanticism fiction often forces onto stories about self-improvement and education, adds a filter of social class and struggle, plus his fascination with human behavior to craft a work that shows a filmmaker at the height of his powers. In typical Wiseman fashion, we are thrown into a world with which we think we are familiar, but his camera has access to places that we didn’t even know existed within the NYPL.

A large part of the film is dedicated to showing the multitude of talks and discussions by artists and intellectuals that take place at the library. People like Richard Dawkins explain the problem with modern religions, Elvis Costello shows audience members footage of his late father playing with his band, and Patti Smith talks about the essence of memoirs explaining she’s interested in capturing “the truth of her real time.” We also see archivists carefully photographing enormous maps and prints, and artists hard at work recording audiobooks. If these moments don’t make people want to renew their library cards immediately then probably nothing will.

Without becoming pamphletary, Wiseman creates the ultimate commercial for an institution that many of us might have been taking for granted. Part of the pleasure in Ex Libris is discovering truly how much the NYPL provides the city. We see library employees helping people with the most extraordinary requests, such as a moment in which a woman is trying to find the town her ancestors came from, or a lecture about Marxism and slavery. We also see executives discuss the ways in which they can cater to people with disabilities, and also the homeless who tend to use library branches as places to sleep.

But rather than just exalt the achievements of the NYPL, Wiseman also points out how it also tells a story of the extreme differences in social classes. At the Schwarzman building we mostly see a combination of white people and tourists who come in seeking knowledge as pleasure, while in branches in the Bronx and downtown, we meet people of color who come to the library to learn how to use laptops, or receive advice on how to find employment.

It’s when the film juxtaposes the haves and have nots, that it proves to be one of the most relevant works to have premiered since the 2016 election. Wiseman posits the NYPL as somewhat of a rogue agent in public service, whose mission truly is to help everyone who asks. With its mission to preserve knowledge, history and facts, helping immigrants, and opening its doors to the poor, it becomes clear that the NYPL represents everything the current administration stands against. This notion makes scenes in which we learn of budgetary problems and things the institution lacks, take on an urgency that should invite us to act, perhaps make a donation, volunteer, or simply be more thankful for its very existence. Who knew a documentary about the library could turn out to be the most thrilling political film of the year?

Ex Libris: The New York Public Library is now playing at Film Forum and expanding in the coming weeks.