Chinese artist/activist/dissident Ai Weiwei—a man deeply entrenched with the social media scene so his voice can be heard around the world—acts by responding to his opponents. A self-proclaimed chess player awaiting the government, police, critics, etc. to spin China’s oppressive nature as ‘being better than it was’, he chases his detractors around the board fully aware checkmate is impossible. But despite knowing full-scale victory is futile, Weiwei refuses to yield or take his freedom for granted. Willing to spend hours inside bureaucratic labyrinths to instill change, time is never deemed wasted since his inevitable defeat brings with it the power to critique through rational and passionate discourse. One must work the broken system to expose its tyranny, bravely defying injustice through one’s fear because the alternative’s silent acceptance is infinitely worse.

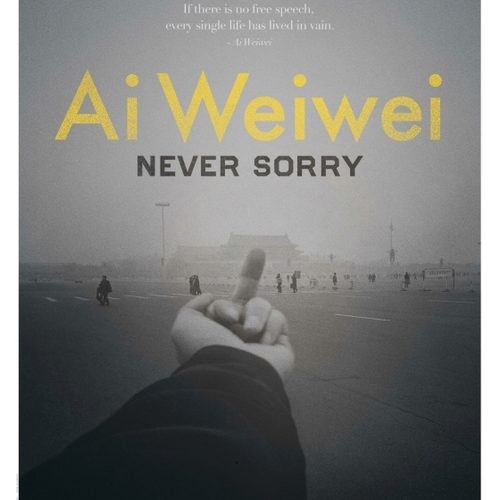

Alison Klayman‘s 2012 Sundance Film Festival Special Jury Prize winning documentary Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry is less a great film as much as great advertising for the world’s most powerful contemporary artist’s incessant struggle. Beaten, imprisoned, and under constant surveillance, Weiwei’s vocal war against Communist China has only escalated as they’ve tightened the noose. An international phenomenon through blogging, art exhibits, and an over 150,000 strong Twitter persona (@aiww), the more his reach is suppressed locally the further it expands. He is a commodity donated freely across the internet to show his fellow citizens they shouldn’t have to remain under the thumb of a malicious regime. Becoming the brand of Chinese reform out of necessity, he fights for the average man hidden behind the propaganda machine’s façade of modernity. Through him the people will be heard.

Among all the hardships and danger of Weiwei’s political viewpoints, however, what I enjoyed learning about most was his art. Studying at the University of Pennsylvania, UC Berkeley, and Parsons, he documented a twelve-year stint in the United States with his camera—an ever-evolving diary continuing today with camcorders and the World Wide Web. Possessed by heady ideas, it was a show entitled “Old Shoes Safe Sex” at the Ethan Cohen Gallery that first gave him a taste of expressing himself on a larger scale. From his raincoat with attached condom to an independently produced art book trilogy exposing China to the work of Warhol, Beuys, and Duchamp to the destruction of Han Dynasty urns as commentary on the government’s redaction of Chinese history, Weiwei’s scope couldn’t be contained.

Watching as America put itself on public trial during the Iran-Contra affair made seeing his own government hiding behind unchecked power to massacre protestors at Tiananmen Square unforgivable. A fervent desire to rally his people around the need for Freedom of Expression was cultivated and his return home in 1993 to help his ailing father didn’t end upon the poet’s death. Weiwei remained to commence a career as a controversial artist and successful architect. However, winning the bid to help design the 2008 Olympic Stadium—the gorgeous “Bird’s Nest”—brought more first-hand experience to the nation’s ‘fake smile’. Their removal of the poor and complete takeover of the region housing the Games led Ai to denounce it all as party propaganda; his open defiance birthing an international image as a man willing to do anything for his beliefs.

A lot of footage from the past three years is Weiwei’s. Through his own documentaries we see the tragedy of the 7.9 earthquake that ravaged the town of Wencuan, the Chengdu police brutality preventing him from testifying for friend/activist Tan Zuoren, and his brilliant political artwork spanning a Munich mural of backpacks for the 5,335 children who died in badly built schools during the quake and millions of hand-painted “Sunflower Seeds” scattered on the Tate Modern’s floor in 2010. Mix it with Klayman’s interviews of Ai’s friends and other’s of him, the exposure of his less than perfect existence through a son not born from his wife, and imagery his filmographers catch during public confrontations with the police and we’re given a rather all-encompassing look at one of the twenty-first century’s most influential and important men.

But while an amazing story about an inspiring figure in the arts and political spheres, I’m not sure the film is necessarily special beyond its subject. A run-of-the-mill talking heads piece seeking to understand Ai Weiwei’s motivations, Never Sorry‘s lack of unique artistic worth does still provide content for an educational forum. To see someone who never used a computer pre-2005 blow up into one of the internet’s more vocal orators is amazing; watching him use social media to inflict social change a perfect example of our new global society’s power. The sad truth is that those who could benefit most from hearing Ai’s beliefs as he stands tall against his oppressors—Chinese citizens—will never see it. The ‘Great Firewall’ of censorship is simply too steep a climb for the masses unaware of the pressure their numbers can inflict.

Klayman’s unfettered access to Ai during this tumultuous time is a Godsend as far as disseminating his message and introducing people like me to the art alongside it. Work like “Grapes” shows his eye for structure and the reappropriation of antique Chinese furniture while “Nian” keeps the memories of so many families’ one and only child alive. We see the love of a mother, wife, brother, and myriad friends hope Weiwei survives his controversial life, already successful in raising awareness of the social strife keeping China from truly moving forward. Many already know his name and actions—a slew of t-shirts seeming to make him the new Che Guevera—but few are probably aware of the man himself. Klayman sets the record straight here, expanding his reach and legitimizing a fight his enemies are still scrambling to keep under wraps back home.

Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry hits limited theaters on Friday, July 27th.