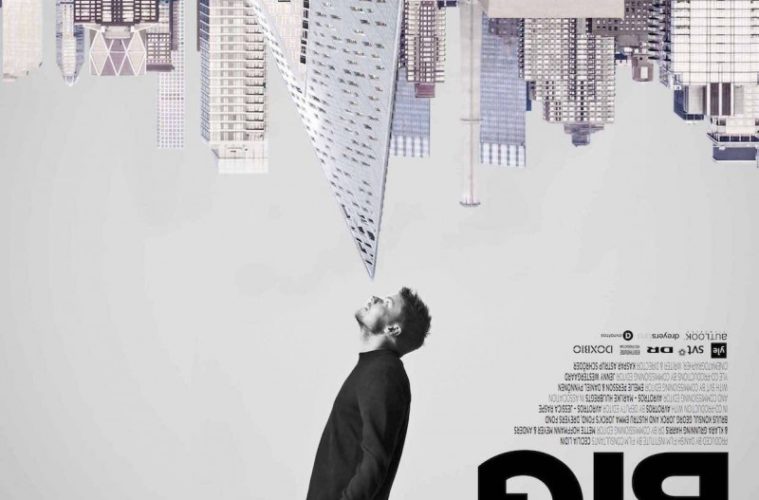

Grand ideas changing skylines and sidewalks take center stage in Big Time, an illuminating portrait of starchitect Bjarke Ingels. Directed by Kaspar Astrup Schröder, he rides shotgun for the young architect as he transitions his practice from Copenhagen to New York. The move, around his 40th birthday, is marked with some tension as his design from BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group) has trouble retaining its European clients as Ingels puts down roots in North America. While here, he works on projects like Two World Trade Center with the Silverstein Properties group and West 57 with Durst Organization, which houses the only movie theater in New York City currently showing the film.

On camera these developers praise the BIG’s team for their willingness to be flexible on these grand projects, while Ingels finds himself battling his patrons over oxidized vs. painted surfaces in a particularly fascinating scene as he expresses disappointment with how a prototype unit for West 57 appears on an overcast day in a field in Pennsylvania. Big Time, however, focuses largely on the creative process as Ingels intimately sketches out the concepts and thinking behind a few signature projects, including a ski slope on top of a clean power plant in his hometown of Copenhagen.

As filmmaker and cinematographer, Schröder’s approach is conversational, following Ingels from client and staff meetings to medical appointments and back home where he offers a brief personal glimpse into what fame and obsession have done to his personal life as he battles a health scare. What motivates Ingels is his own immortality and the scale of which he’s working–an architect only gets so many multi-million and billion dollar projects to make their mark with. His idols all died young with projects under construction and on the drawing board. One big missed opportunity that the film hints at but doesn’t provide examples of is BIG’s smaller-scale work. No doubt this interest will inspire some Googling on the way out of the theater.

Combining intimate small-screen moments at a very human level, including a CATscan, with compositions of Ingels as he is framed to feel alone in elegant posh loft parties with aerial photography of BIG’s signature properties, Big Time is a slight yet intimate portrait of a modern genius. Films like this though are often the first draft of history, and no doubt this will be the first of a few feature films about Ingels. Schroder and his subject do have a nice casual familiarity; hopefully he’ll check in on Ingels every ten years or so.

Big Time is now in limited release.