In an ironic way, Not Fade Away is perhaps most interesting when it’s explicitly referencing the small-screen roots of its writer-director, Sopranos honcho David Chase. Sprinkled throughout the film, which is Chase’s feature debut, are magical moments of characters sitting in front of a black-and-white television screen, allowing themselves to be transformed by what they see. A delicate close-up of Bella Heathcote basking in a Rolling Stones rendition of “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” a farther-back view of James Gandolfini tearing up to a tune from South Pacific — these are affecting touches that let the actors peel back the layers of the screenplay’s relatively regimented characterizations.

But the success of those beats only rarely translates to the film at large, which is so obsessively enamored with the events and the feeling of its era — the post-JFK assassination years of the 1960s — that it forgets to make its specific narrative as involving as all the bits of historical recognition. There’s obvious appeal in the story of a group of teenagers forming a no-name band during this time period, but the material Chase lands on never quite convinces us that this particular pre-adulthood band is more worthy of special treatment than the innumerable others that were surely popping up at the time.

And perhaps that’s the goal. Perhaps, in the scrawny, insecure, New Jersey-bred Douglas (John Magaro), Chase was primarily — maybe even exclusively — attempting to tap into a steady universality. But there’s an aspect to those admittedly noble intentions that keeps the film from ever fully waking up. We identify with Douglas’s trajectory — we like when he gets promoted to lead singer ahead of the pot-smoking Gene (Jack Huston), and we like that this helps him win over his high-school crush, Grace (Heathcote) — but when it comes time to really drill down a precise dynamic, the film settles for broad strokes, Twilight Zone clips, and quotations from Orson Welles.

The real movie here is the one between Douglas and his father (James Gandolfini, in a lively, versatile performance), and I found myself missing it dearly whenever Chase opted to go back to the well of showing Jack Huston’s increasing preference for drugs, or Bella Heathcote’s angelic stare, usually directed towards Douglas as he tenderly covers the famous songs of the day. (To her credit, Heathcote does have a captivating look — it’s when she and Douglas actually begin talking that their dynamic begins to lose some of its passion.) The Molly Price character, Douglas’s mother, is another example — her hyperactive, nightmare-induced stress is funny at first, and then less so when we see it for a seventh or eighth time.

The father-son stuff, too, is the one area in which the film legitimately appears to embody something about the philosophy of that time in America. Too often, Chase is content to give that responsibility to the unsurprisingly great Steven Van Zandt-produced soundtrack. With Gandolfini’s role, though, Chase unlocks a revelation that should’ve received more fleshed-out attention. Here’s a guy who’s much more than his classic-suburban-dad mannerisms suggest. When he lashes out at Douglas upon discovering his son’s Bob Dylan haircut and Cuban heels, it feels like an expected gesture. Less expected, however, is the rationale behind it, which involves a fascinating concept about how two very similar men can live two very dissimilar lives when they’re separated by a generation.

But that’s a tougher story to pull off, and Chase deals with it by sidelining it in favor of Douglas’s coming-of-age ups-and-downs. I have only promising things to say about the fresh-faced Magaro — who recently turned in some nice supporting work in Josh Radnor‘s Liberal Arts — but I’m far less enthused by the character he’s playing. Douglas, while undergoing no shortage of relatable ordeals during the course of the film, still never quite jumped off the screen for me. He’s a weirdly static character, which works at odds with the film’s standardly nostalgic overall tone. A personality like that could’ve worked, especially within this cultural context, but it calls for a much different approach to the storytelling. In this respect, Not Fade Away sometimes plays like a film that wants so badly to be episodic, but merely winds up being indecisive and uncertain.

There’s a recurring line in the film — something to the effect of music being “10 percent inspiration” and “90 percent perspiration” — that, when inverted, sort of reflects what doesn’t work about the film. There’s so much clear inspiration at play here — listening to the soundtrack, you get the sense that Chase probably found his story in the lyrics and melodies of those songs — but there’s precious little of the sweaty grunt work of intense character building, and the aforementioned universality angle becomes increasingly relied on like a crutch, keeping the film’s most exciting ideas at a distance.

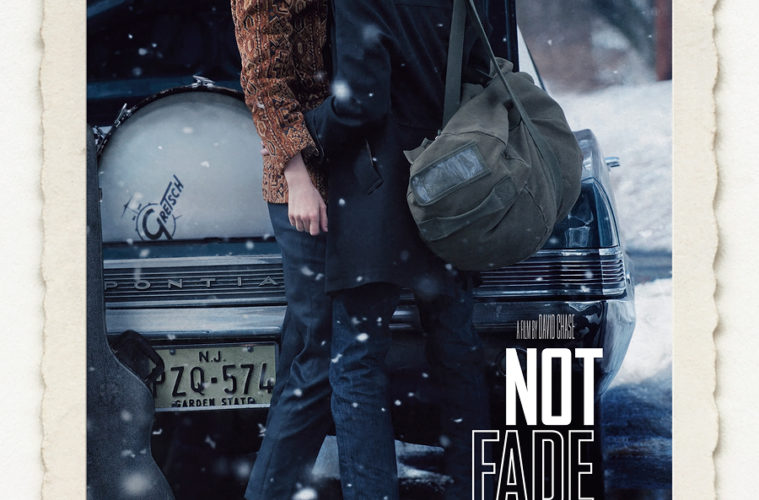

Not Fade Away screened at NYFF and opens on December 21st.