The head of Karl Marx glooms over Chemnitz, Germany — figuratively, as this city was once part of the Eastern Bloc, formerly known as Karl-Marx-Stadt, and literally, as a 40-ton stone bust of him is too massive to be taken away. In Karl Marx City, documentarians Petra Epperlein and Michael Tucker use this place as both title and backdrop to reflect on past and residual damage caused by the G.D.R. (German Democratic Republic) and its conspiratorial abuses of power under the banner of Marxist ideology. Its narrative follows Karl Marx City-born Epperlein in a search for answers about her childhood, identity, and father.

When Epperlein’s father committed suicide in 1999 (a decade after the fall of communism), he left behind a rushed letter signed “Best regards” and a convoluted string of conflicting questions and histories involving the Stasi (Ministry for State Security, also known as East Germany’s secret police). Marx’s Eleventh Thesis reads, “Philosophers have hitherto only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” Epperlein and Tucker take on the task of visual philosophy in their work, interpreting the superficially defunct world of Soviet Germany and this very personal story in a way that calls for the vigilance of contemporary audiences in an age of digital information and the N.S.A.

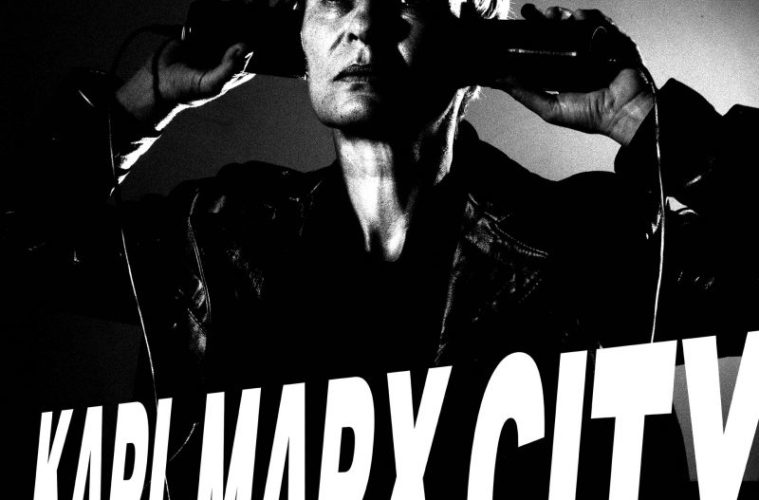

Epperlein acts as the film’s physical narrator — her sister, Christa, narrates in voice-over — and narrative link. Armed with sound equipment, she walks the stone streets of Chemnitz and the stairs of Stasi buildings. The slight noise of her solid-heeled steps and steady breaths abruptly transition into overwhelming, immersive archival audio. The tracking shots of her walking and wandering intrigue but turn tired and meandering in visual repetitiveness, lingering too long on an action that no longer sets the tone nor divulges new information. The black-and-white cinematography transforms its stark surroundings into a sumptuous sight, but this visual depth is spoiled by subtitles with light pink backgrounds reminiscent of snippets from a telegram or letters cut out of a magazine.

Karl Marx City also features quick montages of familiar Soviet and Soviet-era images and clips — Marx himself, Ronald Reagan, the Berlin Wall, etc. — that are meant to contextualize the stories for its audience but instead dumb the film down and bland it out. In one blink-and-you’ll-miss-it throwaway moment, a feather-haired Sylvester Stallone speaks on how the audience typically wants good to triumph over evil. We are told about Indianerfilme (“Eastern Westerns” in which the Native Americans were presented as the heroes) without enough time to process its significance before the next set of clips. Most of City‘s more solid information is presented through talking-head interviews with Epperlein’s family and friends, as well as Stasi experts and historians, but they don’t quite answer why this story is important to a wider audience than those interested in East German history and abuses of power. The filmmakers manage to imply its grander meaning through vague statements about personal privacy and security, but they don’t convey it convincingly or thoroughly enough for an audience unfamiliar with the G.D.R.

With a clearer focus, Karl Marx City could have been the Stasi version of What Our Fathers Did: A Nazi Legacy or Inheritance, or, with more intimacy, been akin to an East German No Home Movie. While we’re told that there is 111 km of Stasi archives informing on over 17 million people and shown the archive storage units, this film spends an inordinate amount of time on Epperlein in her Sony Stereo Dynamic headphones and sensible heels. Oscillating between personal documentary and a scattered historical record, Karl Marx City leaves dramatic tension and narrative threads by the wayside in favor of casting wide thematic webs.

Karl Marx City screened at the New York Film Festival and opens on March 31.