Christian Linaban’s Aberya feels like an attempt to define ‘modern’ Filipino cinema; casting off so many of the industry’s old tricks in favor of a shifting, aimless identity that chases after art-house but ends up on some deranged, filthy side-street. In this case, that dubious destination is Tripping Hipster Alley, circa the late 90’s. There’s not going to be a clear consensus between viewers on what exactly they see in the film, whether or not Linaban intends for such unbridled convolutions, and what, if anything, it all means.

At the end, I was more irritated than bewildered, but my consensus strangely still mirrors that of colleagues who were reasonably entranced; Aberya is undeniably unique and unencumbered by the cookie-cutter apathy of the mainstream. When you are attending four or five movies a week that have seemingly been churned out to pacify the McDonalds’ tribe, this incidental rebellion towards tradition looks enticing; as a hungry festival goer looking for a slice of tasty Filipino cinema, there’s far less to be satisfied about.

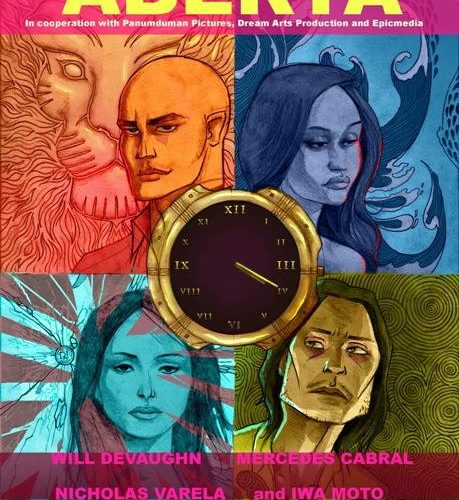

Aberya follows the cyclical journeys of four characters, including the Fillipino-American boxer Lourd Villegas who has come to his parent’s homeland looking to make a connection, his intended Eve, who’s a theoretical nurse with an arcane sex tape circulating the internet, the dealer Mike, who has attracted the scorn of the universe with his attempts to time-travel via drug trips, and Angel, once a nun who’s back-story delves darker than the other three and misappropriates enough Catholic imagery to make hard-core heathens blush. That cabal of ferociously idiosyncratic characters likely has some cinema adventurers running to get their tickets, and others ready to hit the back button. This is no doubt intentional, and Aberya is nothing if not studious when it comes to drawing out the unconventional promise of its inhabitants.

What proves problematic and less intriguing is the way Linaban approaches the construction of his film. All of his philosophical conceits have been sunk into senseless stylistic tics, like Villega narrating his life as if he’s the star of some reality program, or the time-traveler’s retro hallucination sequences, that betray the film as a tedious pretender instead of something visionary. Vision– one of a singular, confident purpose– is lacking here. There’s nothing more infuriating then hearing vocal critics slam an ambitious or difficult film by complaining that it doesn’t meet mundane standards of narrative or expectation. Nonetheless, when disgruntled patrons of Aberya complain that the film is gaudy, too talky, and generally high on its own pomposity, don’t immediately dismiss them as Philistines who would rather munch popcorn then survey art.

Criticism of Aberya’s purposefully difficult structure and mode of expression can’t be evaporated by slapping it with a moniker like ‘challenging’ or ‘polarizing.’ Here, descriptors like ‘sloppy,’ ‘unfocused,’ and ‘lacking discipline’ come to mind, and Lanaban proves to be a fearless filmmaker that hasn’t yet developed into a canny or thoughtful one. The navel-gazing that passes as dialogue doesn’t mesh with the performances, which are largely very good and hint at what the movie might have been, had it simply chosen one path and walked it with confidence. Will Devaughn’s Villegas could have been a great protagonist, but what he probably needed was one of those scorned, traditionalist narratives that this production smugly looks down on.

Aberya plays at NYAFF starting today.