On my last night at the Morelia International Film Festival, dinner took place at Lu, a restaurant specializing in Michoacán cuisine. Over rollos de jicama and tostada San Pancho, conversation ranged from TCM’s Eddie Muller on Dorothy B. Hughes, director Gregory Nava on the second Franco-Mexican War, and Stellan Skarsgård musing about the daily demonstrations that closed thoroughfares around town.

Skarsgård came to Morelia to screen Sentimental Value, his first collaboration with Joachim Trier. In it he plays Gustav Borg, a film director long estranged from his daughters Nora (Renate Reinsve) and Agnes (Inga lbsdotter Lilleaas). At a point in his career where mounting productions have become difficult, Gustav tries to involve a reluctant Nora in a deeply personal screenplay that’s also attracted Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning), a Hollywood star.

During the meal, he talked about the film in terms of his relations with his children, with directors, and with art in general. Later, we spoke over Zoom about his acting process as the film opens in U.S. theaters.

The Film Stage: Can you talk about building Gustav’s character? You’ve said that the role wasn’t very developed in the script. Do you write notes and prepare a backstory?

Stellan Skarsgård: I find if I sit at home and create a backstory, create a lot of things that happen to Gustav through his life, then I have to stick to it. Sometimes you hear actors say to the director, “Well, my character wouldn’t do that.” How do you know? Why do you think your character is more simple than you are? Your character could be more complex and have more sides than you can ever imagine. You have to not to minimize the character to your own imagination. You have to leave it open.

That doesn’t work all the time, does it? When you’re Baron Harkonnen in Dune, basically sitting in a tub of oil, how much freedom do you have?

Yeah, I didn’t think about his childhood. He might have been molested as a child, but I did not use that.

How uncomfortable was that role?

Rather uncomfortable. It was pretty warm, but it was disgusting. Oily. I was held down with weights so my costume wouldn’t float up like a balloon.

With Gustav, how much did you base on your own experiences?

I’m basing everything on my own experiences because I’ve got nothing else to base it on. But I don’t try to put my own experiences, on a superficial level, into a film, or my work. It’s more like I am the clay, the material from which I make these characters. They’re my feelings.

But Gustav is a very different man from me in many ways. Though we’re supposed to be the same age, he’s definitely from another generation; he’s a more traditional kind of man. My relationship with my children is also very different, much more relaxed.

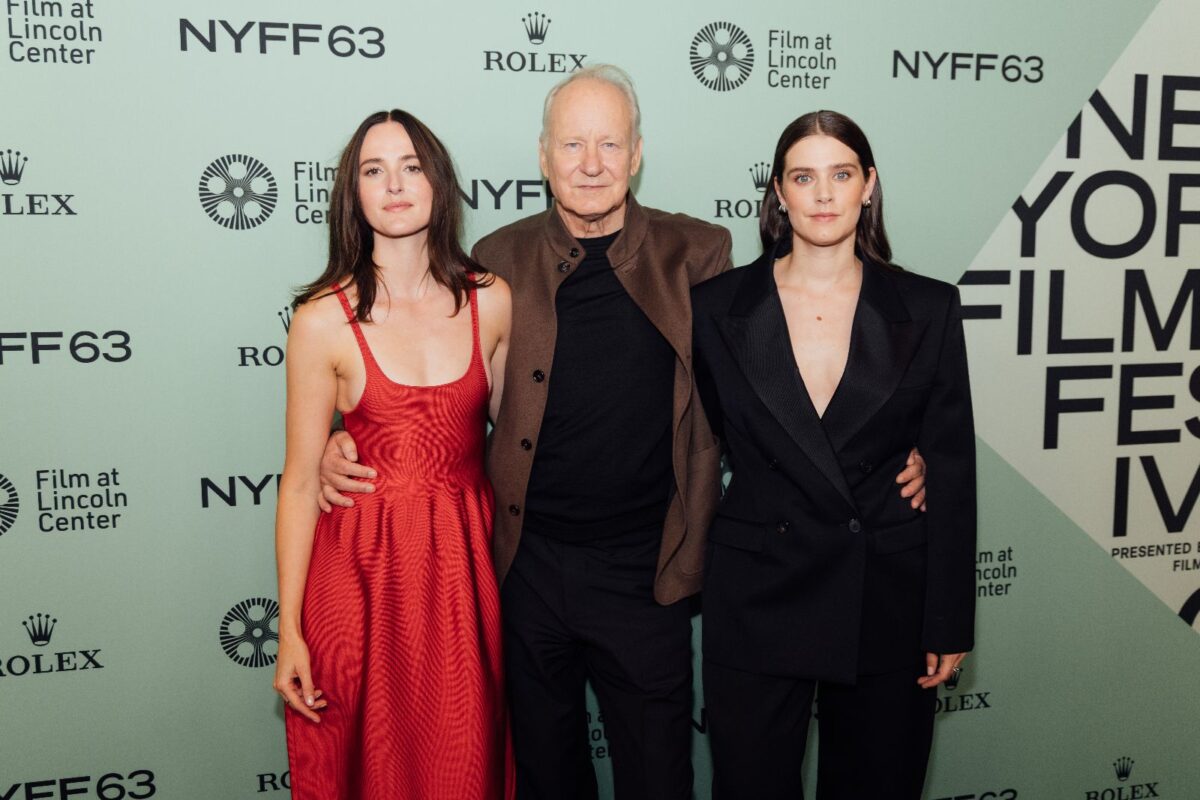

Sentimental Value premiere at New York Film Festival. Photo by Sean DiSerio.

What about your experiences with directors? Did they come into play?

Well, my first instinct was, of course, revenge––the chance to get back at all the directors I worked with. I gave that up very soon because, first of all, the character doesn’t have to be a director. He can be an artist––a painter, a musician, a writer. It was important for me to show that in his profession, in his art, he is very, very sensitive. Very capable of describing feelings and emotions and psychology, which he is incapable of in his personal life. In real life, his tools are too clumsy.

Do you feel that’s normal for artists? That which makes them creative can possibly make them not very nice people to know personally?

It can. It doesn’t have to be like that, but it can. I’ve been filming four months a year for the past 30 years, and then changing diapers for eight months a year. That’s sort of the proportion. But that’s not to say that I was always there. I might have been absent in my mind, in a way.

When I ask my eight children what kind of dad I was, I get different answers. Because some of them needed a lot of attention and some didn’t. It doesn’t matter, really. No matter how good you are, you’re still imperfect.

As an artist, your job is your life. It’s you, your being. It’s who you are. That means it is all-encompassing; it sort of swallows you more than any other job does. I think if you give up your artistic work, or if you compromise with it, you are no longer you because that’s your identity. It’s always difficult for artists to combine work with a personal life, I think.

Do you believe artists have to suffer for their art? Gustav certainly does.

No. You don’t have to suffer. I mean, there’s always normal suffering. Life brings it to you. So you get enough suffering from life as it is that you don’t have to search for it. Suffering doesn’t make you better.

Is Gustav a good director?

I decided he was. I thought of him as from a different generation, a sort of Eastern European director from the mid-sixties––someone like Miklós Jancsó, someone who uses those long takes. But I also wanted you to see Gustav’s sensitivity when he works with Elle. That’s the other side of him that you have to show in order to put his incompetence with his daughters into relief.

Isn’t he incompetent with Elle as well as his daughters? Like when he lies to her that a prop stool is the one his mother used to commit suicide.

That’s a joke. I mean, it’s partly brutal, but it’s funny. And he can say that without being unloyal to Elle. She asks about the suicide all the time. His answer is, “It’s not my mother. It’s not about my mother.” He says that over and over again. And it isn’t, really. It’s about his daughter, but he won’t tell Elle that.

What’s interesting about him is more what he doesn’t understand or what he doesn’t know. He is not capable of reaching out to his daughters, but he doesn’t know that. He doesn’t see his movie script as a vehicle for communication or anything like that.

So it’s frustrating for everyone involved. Neither he nor his daughters will find satisfaction.

The final gaze in the film is interesting. It’s such a delicate moment. They are sort of surprised at what they felt when they did this scene together. And that is wonderful. It’s not the kind of happy ending where problems get solved, but it gives you hope for an opening, a hope for forgiveness. For reconciliation. Which may be a happy ending.

I like your use of “opening,” because Nora goes into her father’s project not wanting to do it at all. When she does the oner at the close of the film, she sees a new world, a new way of looking at her life and her father.

Absolutely. In that sense, maybe you can say that art heals. Maybe doing that role in this particular film helped her understand a little more about herself and about her father. She’s just as surprised as he is.

Do you think your characters have anything in common? Are you looking for something specific in a character?

As an actor, you’re just a hired hand. You go into someone else’s universe and try to be useful, help the director create a world. So it’s very hard to have a sort of an artistic stamp that continues through your career. It’s not like being a painter where you can say, “That’s a typical Braque,” or whatever. But I hope that my vision of humanity is somehow palpable. It’s somehow recognizable in my characters, even if they’re bad guys or monsters––whoever it is reflects my vision of the world. That’s very vain and stupid to believe. But I hope, in a way, it does.

You create art in part to present your vision of the world. What I find remarkable is that you can find the same humanistic view in such a wide range of characters. Like Nils from In Order of Disappearance––he’s a brutal killer who, at the same time, is avenging his son.

He’s wrong, but that doesn’t make him less human.

You’ve said that Gustav makes stupid decisions, but you still needed to make him likable. How do you do that with a murderer like Nils?

By showing his humanity. I mean, not everybody has to be likable. But they do have to be understandable in a way. You have to understand that evil deeds, just like good deeds, are not coming out of a vacuum. You need fertile soil to grow goodness. And you need fertile soul for evil as well.

You can show the complexity of a character in a second: just a little glimpse in the eye, a little hesitation somewhere in a gesture, something in the way you say a line. It’s something that brings out the compassion in the audience. You can do it very easily, very fast, and you don’t have to compromise with the role in other senses.

Like Luthen Rael in Andor, who has to send his friends to their deaths to keep the revolution going. We can still see his compassion, his remorse.

Definitely. Tony Gilroy is an expert on revolutions, and on revolutionaries too. He knows the psychology behind revolutions perfectly. He understands the conflict inherent to it.

You don’t like working in TV that much?

No, because I can’t do what I can do in Joachim Trier’s films. I made an exception for Andor because that wasn’t traditional television. Normal television writing is: everything is in the text, everything is explained. So it doesn’t matter who plays it or who directs it; people will understand it even while they’re doing the wash or cleaning the kitchen. It’s poor man’s storytelling, easy and cheap. I get depressed when I watch it.

Sentimental Value is now in limited release.