In the procedural genre, where “bad cops” frequently reveal themselves to be law-enforcement geniuses, it remains shockingly refreshing to see a film where the bad cops are, in fact, bad cops.

Of course, this isn’t the only way in which Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder distances itself from the Hollywood standard—not even close. (Its most obvious point of comparison is David Fincher’s Zodiac, though to properly compare and contrast the two would require a lengthy essay of its own.) Imbued with the mercurial, melancholic tones and indignant social consciousness of the Korean New Wave superstar’s finest work, Bong’s 2003 masterpiece remains a haunting chronicle of impotence, frustration, systemic dysfunction, and unfathomable injustice wrapped up in a rain-slick neo-noir coat. Loosely based on the real-life serial murder case that shook South Korea during the late 1980s, the film follows a task force of baffled detectives, led by schlubby everyman Park Doo-man (longtime Bong collaborator and Korean New Wave mainstay Song Kang-ho), as the bound and violated corpses of young women begin turning up around the sleepy rural city of Hwaesong.

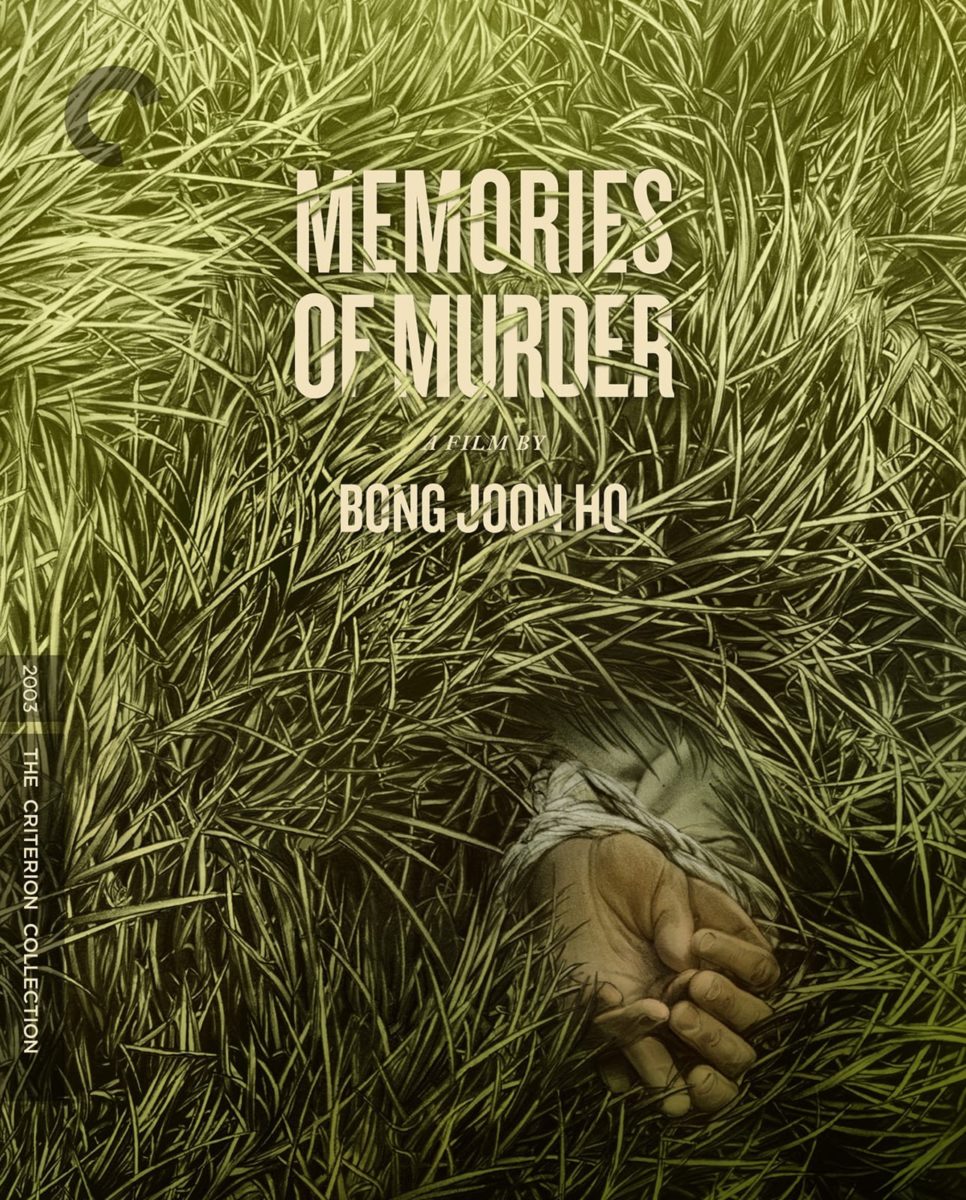

A stately, elegiac tone distinguishes the film from the average crime thriller right from the opening scene. A sprawling, green-and-golden grain field (soon to be one of the film’s main locations) is presented in stunning, color-rich compositions by DP Kim Hyung-koo, accompanied by Taro Iwashiro’s somber, bittersweet score on strings and piano. Curious children frolic and tease harried grownups amid rustling sunlit waves of stalks and mud––while unbeknownst to them, Detective Park locates a grey, rotting young corpse in a roadside gutter. She is glimpsed in pained, fragmentary close-ups, eyes open with skin like spoiled leather, as leaves and hungry insects shrink from Park’s uncovering. Sunlight, for the rest of the film, will give way to overcast skies and dark nights until its final scene. Rarely has a work of genre cinema so immediately and vividly established the emotional texture of its time and place, both hyper-specific and mythologically universal, while driving in the central metaphors of its narrative.

Living in a filthy, microscopic apartment with his girlfriend and largely indifferent to the social unrest of 1980s Korea, Park fancies himself a kind of Columbo-esque supercop in spite of his circumstances. He boasts to colleagues about his superior criminal-catching intuition and enthusiastically bends and breaks the law in pursuit of often harebrained theories: in one ludicrous sequence he convinces himself that the killer has no pubic hair, and contemplates how to put this theory into action. Together with his brutality-loving partner, Cho Yong-koo (Kim Roi-ha), Park loses and fabricates evidence, imprisons and tortures suspects, and dismisses promising leads suggested by colleagues to pursue his own increasingly dubious ones. Tensions rise when young, college-educated big-city detective Seo Tae-yoon (Kim Sang-kyung) is brought in from Seoul to assist in the case. Seo’s intelligence and professionalism initially appear to put a needed check on his more barbaric colleagues, but as the investigation is thwarted at every turn by the limitations of South Korea’s mismanaged, underdeveloped police system—and as Seo’s own emotional distance from the terrorized Hwaesong community narrows—even the “good cop’s” methods and motives become increasingly fraught.

Bong’s screenplay, co-written with Shim Sung-bo and based on a play by Kim Kwang-rim, moves for much of its first two hours along the course of a standard, nevertheless engrossing procedural: crimes are committed, leads are followed, suspects are interrogated, rinse and repeat. But a more expansive, novelistic quality emerges more gradually, through the seams. Bong is a master of controlled chaos, and while each and every scene directly pushes this plot along at a brisk pace, the film’s meticulously constructed nature is disguised beneath sequences that feel effortlessly organic and genuinely surprising. The film’s rhythms are curious, an odd stop-start that expands and contracts the flow of time invisibly to conscious observation, as it unravels a messy series of events which infiltrate the humdrum normality of characters’ daily lives. Detectives eat meals (a trademark Bongism), have off-color conversations, brainstorm aimlessly about the job and mingle with civilians in ways that all conveniently (and often unexpectedly) lead back to the central investigation. In one of the film’s few arguable missteps, Bong aims to tighten suspense by films some pre-murder scenes from the victims’ perspective; though they sidle in some indubitably creepy shots, these bits feel like lurid exports from an altogether different, much trashier movie.

Murder was Bong’s sophomore feature, yet here with the skill of a world-class director he conveys a tapestry of character relationships, themes and metaphors with utmost economy using every cinematic means at his disposal. Particular moments stand out for their breathtaking artistry: A momentary shot of Detective Seo in a garbage dump takes on the quality of cosmic horror, backgrounding Kim Sang-Kyung’s doll-sized silhouette in a horizontal strip of smoky dim light, as he gazes over a smoldering mountain of random, lifeless refuse that threatens to consume the entire screen. In one ingenious deep-frame composition, three different scenes involving four major characters play out simultaneously before coalescing into a warped, cheeky punchline, never seeming the slightest bit confusing or ostentatious in the process.

An episode late in the film marks the finest narrative achievement yet in Bong’s career. Peripheral to the straightforward advancement of a detective plot throughout its first two thirds, the script lays down numerous threads of character, theme, metaphor, and social commentary that appear secondary to the main narrative; then, in one pivotal sequence set in the neighborhood diner, each thread knots together into a sudden outburst of violence that transfigures the meaning of all scenes before and after. Whipping up a startling catharsis that ambushes the audience from the shadows of the film’s subtext, the restaurant melee scene is such a masterfully laid dramatic snare that it hits with lethal force even on repeat viewings. And it isn’t even the film’s conclusion, of which there are two: a white-knuckled staredown with the truth and a distant, chilling epilogue that each devastate in equal and opposite ways.

If this all sounds a bit reminiscent of a certain other Bong Joon-ho film that swept last year’s Academy Awards, well, that’s because it is. Like Parasite, Memories of Murder pulls off a volatile extended high-wire act, balancing comedy, horror and a seemingly chaotic rat’s nest of characters and plot threads before pulling out a carefully coordinated shock of a finale followed by a somber, haunting epilogue. And as in Parasite, Bong refuses not to sympathize with his ostensible villains, preferring to depict them as functionaries of a violent and dehumanizing system over “bad apples.” Despite the destructive consequences of Detective Park’s hapless arrogance, by viewing the story through his eyes (and thanks to Song’s affable performance) the audience sees less of an authoritarian bully than a crushingly ordinary man, neither malicious nor heroic, whose self-rationalizing mythology is gradually shattered by a cruel and chaotic truth. He wants to bust the bad guy and solve the crimes, but in his (internally enforced) myopia and (externally enforced) impotence, he just keeps running headlong into walls. Whatever his individual failings, he’s stuck working an unprecedented case in a police force better equipped to suppress the public than protect them––a point driven home when the Hwaesong police force is called upon to violently quell student protests. As the failures and the corpses pile up one after another, Park and Seo’s frustration, despair and guilt grow ever more palpable.

Murder, in contrast to Bong’s subsequent films, is remarkable for its restraint. While Bong is not above slapstick humor or genre thrills, Murder sticks to a largely grounded and realistic tone throughout, never reducing itself to the cartoon theatrics of his other work. There are no scenery-chewing satiric caricatures or winking dialogues wherein characters explain symbolism to one another. The film’s social commentary, likewise, is remarkably understated in comparison to the noisy and muddled parables of his later years. The political anxieties of militarized, authoritarian 1980s South Korea are a pointed presence in the film, but most of the time they play out as ambient undercurrents in the characters’ day-to-day lives––newscasts, shelter drills, mumbled gossip—until, suddenly, they aren’t.

True to its memorious title, Murder plays out like a bittersweet recollection of a community and its unsettled lives, brutal in the details but faintly nostalgic as it elegizes a lost sense of innocence that existed in Korea’s recent past and the skeletons in its national closet. The gradual sweep of the narrative earns its 2003-set epilogue contrasting the poverty, disarray and communal intimacy of that transitional period with the prosperity and alienation of South Korea’s present. Park, now an aging family man with a corporate job, a clean suburban home and a video game-addicted son, stops on a whim in Hwaesong to revisit the green-golden grain fields, unchanged since that time so long ago, where his greatest failure still haunts him. The final shot—of Song Kang-ho staring deep into the camera with the weight of a nation’s memory and a lone man’s regret—is one for the ages.

Criterion’s new edition restores the film in 4K and has controversially––with guidance from the director and cinematographer––introduced a new green color tint on much of the picture. Bong has always had something of a love affair with green, but its domination of all light in the new restoration is conspicuous to the point where many scenes appear to be taking place in the Matrix. Arguably this matches the dingy claustrophobia and historical detachment of the film’s setting, but it also doesn’t add anything drastically new to (and may take something away from) compositions that already looked gorgeous in HD.

Also included among a bevy of supplements is a new restoration of Bong’s 1994 student thesis film Incoherence, available for the first time with an official English translation. Inspired (according to Bong’s own spoiler-filled introduction) by the episodic structure of Pulp Fiction, the half-hour short follows three seemingly unrelated plotlines of middle-aged men engaged in petty vices before converging them into a sucker-punch twist ending. While stretched a bit thin and clearly more the work of a promising amateur than a fully bloomed auteur, the short is remarkable for presenting virtually every one of Bong’s thematic and stylistic trademarks in embryonic form, gathered together in one place: crass and myopic authority figures, multilayered situational ironies, elites exploiting the common people, mass media as instructive omnipresence, tactically deployed crude humor to disarm the audience, and seemingly chaotic situations that coalesce into a surprising climax. And, of course, the hazy color green.

The new restoration of Memories of Murder is now available on The Criterion Collection and Hulu.