All through Fairytale (aka Skazka), characters recite the opening of the Divine Comedy and Dante’s preamble to his plunge into hell. But the black-and-white world Alexander Sokurov’s souls are stranded in feels closer to a kind of purgatory. A liminal wasteland of derelict buildings, rubble, and skeletal trees, it’s a nightmare yanked out of a Gustav Doré print, and no surprise one of its denizens—none other than Winston Churchill himself—should wonder early on if it is all a (very bad) dream. Churchill shares the hallucination with a number of other iconic figures from the twentieth century, a sordid cast that includes the likes of Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, and Joseph Stalin (add to the mix Jesus Christ, the only bedridden one, briefly caught lying in the same room as the Soviet generalissimo). But Fairytale has no cast, strictly speaking: these four play themselves. The film’s sleight of hand—and the source of its disquieting allure—lies in its technical wizardry. Brought to life by Sokurov and his team of visual-effects mavens, who stitch them together combining archive footage and deepfake technology, the quartet careens in their real-life looks, engaging with one another in an otherworldly walking tour that sits somewhere between Dante and Monty Python.

There’s something subversive about the choice. For all its funereal settings, Fairytale tumbles along as a big farce, stripping its heroes of their mythical grandeur and mocking them as they struggle with their spiritual impasse. God has trapped them all in what’s essentially a big waiting room. And wait they must, taking turns to knock on heaven’s doors only for these to slam shut before them, the almighty teasing the pestilential gang with vague promises that the gates will soon open—just not now. (Curiously, Sokurov places Napoleon in heaven already, much to the dismay of the dictators queuing up for their own place under the sun.)

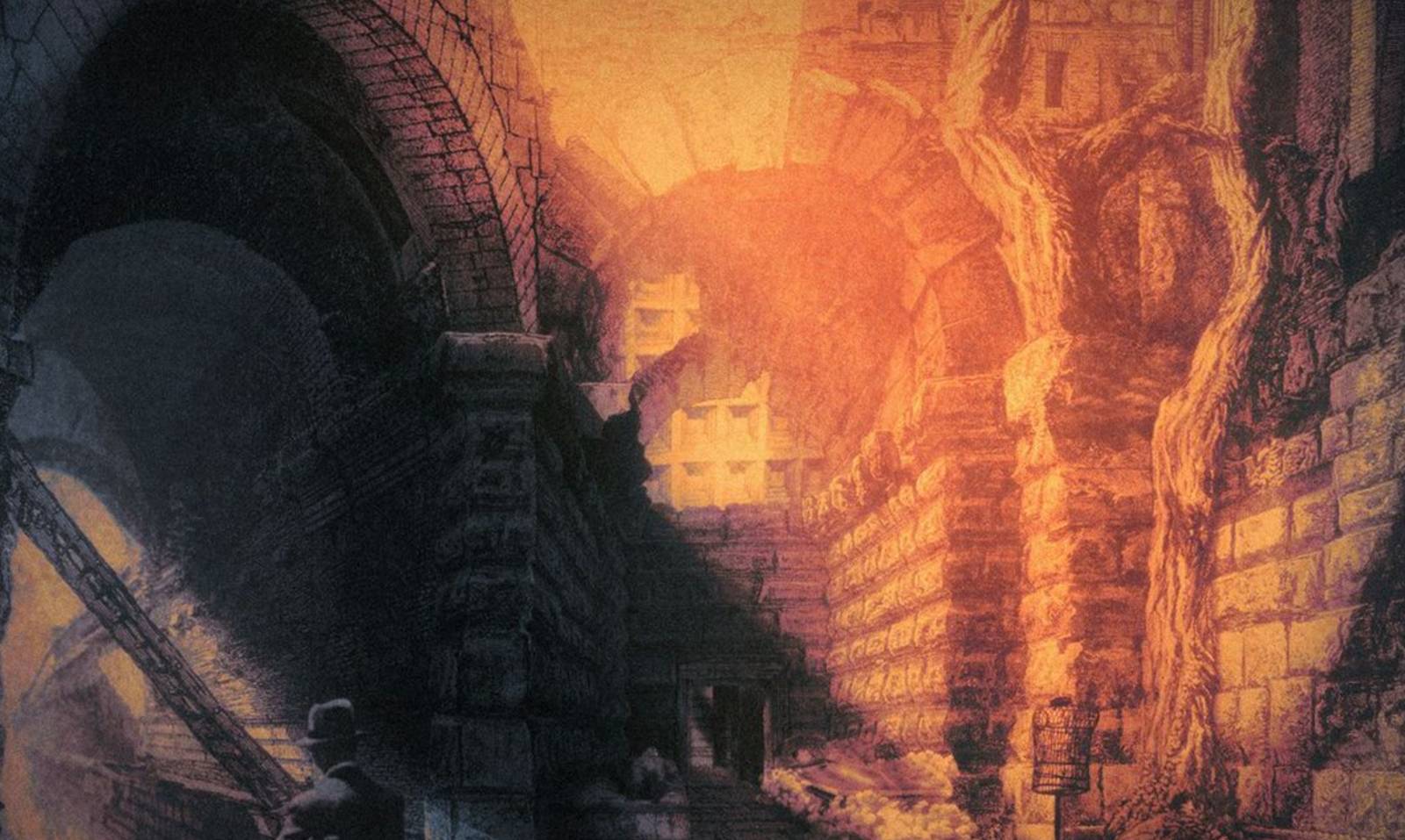

Surreal and deranged as the premise may seem, what follows in this journey through limbo is somewhat straightforward. Dubbed in their mother tongues, Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, and Churchill walk through Fairytale in an endless loop, ridiculing one another and wondering just how much longer they’ll be forced to be stuck with their sworn enemies. Purgatory, as Sokurov imagines it, is a barren VIP lounge. No one else is seen roaming these monochrome vistas; the rare times other souls show up, Fairytale pictures them as a tidal wave of phantoms (are these the millions of innocents the quartet led to death?) flowing through canyons and quarries, their faces and bodies blurred into an unrecognizable, lugubrious shock of shadows. These scenes have a sinister beauty to them, and indeed Fairytale brims with all kinds of details both mesmerizing and haunting. The whole film is bathed in a silvery mist, dust motes twirling and glittering everywhere like nuclear fallout. Stalin and company trudge into the apocalyptic landscape in a restless quest without destination or purpose, and it’s not long before they spawn their own doppelgängers: each of the four begets three identical twins that cram Sokurov’s sparse compositions.

But more characters do not mean more action, just as more chatting does not necessarily translate into more insightful exchanges. Like the strolls, conversations go around in circles, the four talking and poking fun at each other, only to succumb to all manner of more or less ridiculous regrets. Stalin spends much of Fairytale dabbing at his nose, prompting Mussolini to ask if he’s “got the snots;” Hitler whines over Wagner’s nice (“I should have married her!”) and regrets he didn’t blaze London properly; Mussolini mutters that religion “is a psychic disease;” while Churchill worries he may have lost his wife. That Fairytale lacks narrative momentum is part of its own design, and to lament its aimlessness would be to play into Sokurov’s hands. This is, after all, a journey with no real start nor end; the stasis characters succumb to is the film’s own. What’s more troubling is that, for all its intellectual and sensorial intrigue, Fairytale seems to quickly run out of things to say or show.

Gradually, these constant repetitions—of similar exchanges, similar actions—stopped giving me new things to think about, and for a while I let myself be hypnotized by Fairytale’s ruinous backgrounds, and the terrific and disturbing CGI work, which breathes life into the four drifters and the newsreel that immortalized and entombed them. (In a film so concerned with the fate of the soul, that’s perhaps the one resurrection Fairytale captures, and it is courtesy Sokurov and his team rescuing Hitler et al from their audiovisual sarcophagi and turning them into sentient holograms). But even that wears itself out; the film starts to grow a little tedious, as if unable to keep up with the force and scope of its nightmarish design. What remains is a curious oddity, a fable that doubles as a sort of marriage between Sokurov’s interest in digital technology and the figures that shaped, for better and worse, the course of modern history. Its lack of narrative and lopsided structure is part of the point. But lysergic and creatively fertile as its setup may sound, Fairytale is a rather staid dream.

Fairytale premiered at the Locarno Film Festival.