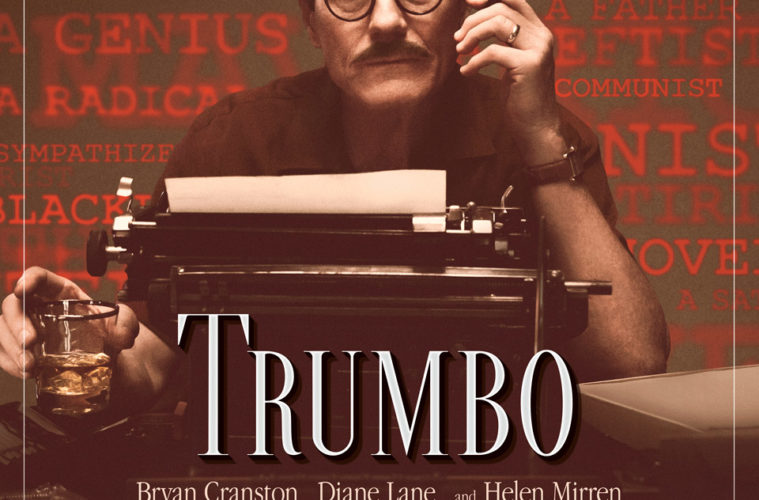

Bryan Cranston is irresistible as Dalton Trumbo, the blacklisted screenwriter of Oscar-winning classics Roman Holiday and Spartacus, in this sparkling period drama surrounding the Hollywood Ten. His larger-than-life performance promises surface sheen rather than cruel dissection of tinseltown’s failure to stand up for those disaffected by the Red Scare. But Jay Roach’s film has the daring to flatten the reputation of Hollywood’s previously lionised – including John Wayne and Louis B. Mayer – marking an intriguing look at post-Golden Age Hollywood, helped by a very funny script from John McNamara.

After the Second World War, Trumbo rose to become the highest paid writer in Hollywood – “a record breaking contract to make shit up,” as he himself refers to it. But in the late 1940s the Red Scare took hold, and Hollywood was among the first to suffer McCarthyist sanctions. Trumbo, who argues his political position is as a “liberal democrat” in the film, is hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee where, along with other members of the Hollywood Ten, he declines to give evidence. Trumbo assumes their political consciences were protected by the first amendment. Instead, they were sent to jail for contempt of congress.

Cranston brings a cunning irascibility to Trumbo, meaning the film isn’t the straight lionisation of the writer that might first be assumed. Trumbo’s way with words, his fluency of rhetoric, is used as much to persuade his fellow writers to suffer the fate of prison as it is to persuade congress of his political position. Trumbo was one of Hollywood’s richest talents – million dollar contracts seem rather contrary to a communist sympathiser. As he later acknowledges, the real victims of blacklisting were the writers unable to make a living. In the case of Louis C.K.’s (fictional) blacklisted scribe Arlen Hird, his wife, children and, eventually, health are lost in the battle for recognition.

Roach, the director of screwball comedies like Meet the Parents, has developed into a successful political drama director, such as 2000 election drama Recount, and Trumbo appears to be his first attempt at a true prestige pic. But his comedic predispositions keep the film’s worthier ambitions in check, settled around a witty script from John McNamara, based on Bruce Cook’s biography. Whenever Trumbo makes a comment on the loftiness of the cause, he’s castigated Louis C.K.’s Hird about how Trumbo “talks like a radical, but lives like a rich guy.” C.K. himself is one of the best elements in the film, wryly articulating the struggle that Trumbo’s wit and work-ethic masks.

Roach’s direction also means that Trumbo’s struggles after prison – he served 11 months in Kentucky – are played more for laughs than for serious contemplation of the struggle against censorship. Trumbo becomes a jobbing writer under assumed names – as many blacklisted writers adopted – at first contributing screenplays to madcap B-movies like Gun Crazy for Frank King (a bubbly John Goodman), and later for his two Oscar wins – Roman Holiday and The Brave One.

There are some witty, cine-literate cameos that arguably underline how much the film is willing to be critical of Hollywood greats the industry has previously lionised. David James Elliot is quite amusing as a pernicious John Wayne, who helped create the censor-supporting Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, and Helen Mirren has a starry cameo as slimy conservative gossip columnist Hedda Hopper.

The focus on Trumbo’s crusade does mean the Trumbo’s family life is underdeveloped, particularly his wife Cleo (Diane Lane), even with a spiky Elle Fanning as his daughter Nikola. Indeed, only in the film’s adoption of Trumbo as an all-American family man does the story feel falsely told, trumping an explanation of why Trumbo became a communist in the first place. But this is Cranston’s show, after all, and he effectively makes his leading man transition from television to the silver screen.

Trumbo screened at that 2015 London Film Festival and opens on November 6th.