Contrary to early, perhaps reactionary, accounts, Rosewater is not entirely devoid of comedy. Of course those who think of Jon Stewart as a comedian first, journalist second will be surprised, but anyone more familiar with his work on The Daily Show will recognize that he does care deeply about the issues he raises. The comedy is how he captures the attention of the politically apathetic, and ultimately how he copes with the absurdities of what is happening in the world. And so it is with the humor in his directorial debut Rosewater – a coping mechanism for a man in a desperate situation. It’s adapted from a book by the real Maziar Bahari (here played by Gael Garcia Bernal) telling an account of his detention in Iran after covering the 2009 presidential elections and the following protests for Newsweek.

There’s a small Daily Show connection in the plot but on a broader level it’s consistent with Stewart’s satire because both are trying to make serious issues accessible without compromising or simplifying them. Rosewater isn’t entirely successful in this regard but it’s a far more interesting and more nuanced portrait of Iran than something like Argo. It helps that Bahari is Iranian but London-based, has a British wife and works for Newsweek, so a westernized viewpoint is justified. Similarly his imprisoners-torturers, “Rosewater” (Kim Bodnia) and his superior, are not cardboard villains – there’s a serious effort to explore what pushes people into extreme rhetoric.

In its montage of TV news footage, Rosewater does come across as a little self-serving, but it also recognizes the media’s limits – Bahari is a fairly high profile case because he was a journalist, but others aren’t as fortunate. Long conversations with his imagined father, imprisoned for being a communist in the 1950s, bring a historical perspective but it’s a shame this very conventional device is favored over the effects of the blindfold (he could only identify his torturer by the smell of rosewater, a point that’s lost despite the title). Perhaps there’s no good way to represent this blindness on film – there’s certainly no way to represent a strong smell without translating its power into images and sound – but to not even try is a missed opportunity.

Still, Stewart puts us in his head in other ways. The psychological torture might not have the impact it needs but we rarely cut outside his cell and never outside the prison, and the claustrophobia does build up. The strongest moments of the film are the moments of levity, or release – Bahari dancing in his cell for example, to music only we and he can hear, while watching it on CCTV is bemused. Scenes like these work better than the film as a whole, where the sheer duration of Bahari’s ordeal fails to make the impression it needed to.

Competently made but a touch insubstantial, Rosewater is a promising debut for Jon Stewart.

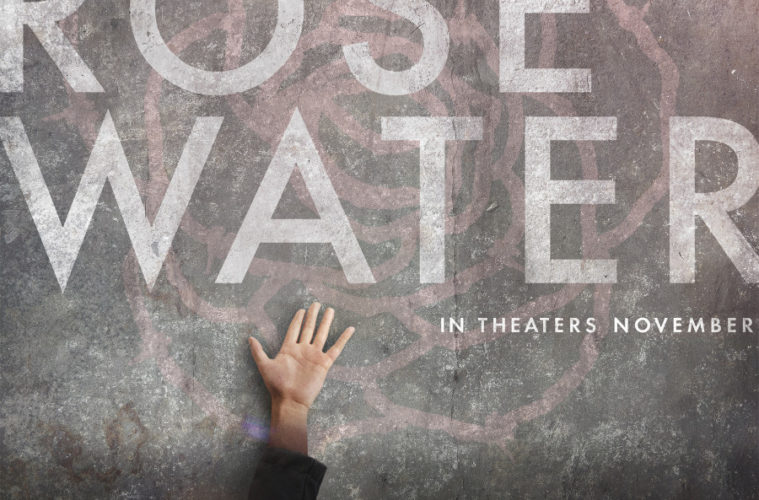

Rosewater screened at London Film Festival and opens on November 7th.