Few figures of contemporary cinema are more shrouded in mystery than Bi Gan, and no film this year posed a bigger question mark than Resurrection, his seven-years-hence Long Days Journey Into Night follow-up that had been subject to much speculation and conjecture. It proved somewhat divisive upon landing at the very end of this year’s Cannes Film Festival, which it exited with a Prix Spécial—a rather clear sign the jury, two weeks into globe-spanning cinema of highly variable strengths, knew they’d seen something, but nothing quite diagnosable.

Amidst such sturm und drang, Resurrection sneaks into the calendar year from Janus Films, which releases it on Friday. A guest at this fall’s New York Film Festival, Bi sat down with us for a conversation traversing his film’s strange path.

Thanks to Vincent Cheng for providing interpretation.

The Film Stage: I used to work for Grasshopper Film, which released Kaili Blues theatrically, then on Blu-ray. It’s nice to finally meet you after spending so much time with that film.

Bi Gan: And I can be where I am now because of what you did.

Well, it’s one of the films that I was proudest to represent. Literally could not keep the Blu-ray on the shelves.

Ten years, thanks to all your work. Very moved and very touched. Everything comes from that. I seem to remember, during the development process, that we had some inquiry from Film Stage, and little did I know that someone actually worked on Kaili Blues in the past.

Resurrection screened towards the very end of Cannes, and there were reports you were working on it until the last minute. I’m always very curious what the creative, physical, emotional process is of making these last-minute decisions, and how much they’re definitive or simply about needing to get the film done.

The cycle of producing this film and making it happen, actually, is quite long by Chinese standards—they tend to have a shorter production time. For me, I sort of don’t mind having a smaller crew but having a longer production time for filming. But for us, we went through three different cycles on and off of shootings, and then we were put on hold—not because of creative leaders and challenges. It’s nothing to do with the creative teams and also our vision for the film; it’s all about budgetary concerns and other concerns. It’s the market concerns and all that somehow creating roadblocks for us to finish the film the way that we want to. And that’s the reason why we stopped production and put it on hold, or on the holding pattern, a few times.

I can say that we actually sort of saved the film doing the breaks, to do everything we can to make sure that this will continue to move to the next stage. So for myself and the creative teams, the investors, the producers, we’re sort of going through the processes of how can we save the film and keep on going. And it’s not until April of this year that… whenever we have this holding pattern on breaks, I always do a rough edit just to keep the momentum, even though we’re still looking for money trying to resolve the issues to somehow to start production again. But I always keep on working and keep on editing, but I do feel that, towards April, the morale was pretty low. And then I thought that I need to bring something positive for the crew because we have been trying so hard to keep it alive for so long and we are so close to the finish line, and I want to somehow bring some kind of momentum to finish this particular film strong.

So I talked to my cinematographer, Dong Jingsong, and also my art director, Liu Qiang, to really think about, “How do you feel about this and what do you think will help us or propel us to move forward even more?” We decided to try out the Cannes Film Festival, and then we used about half a month to really do very preliminary post-production, including sound design with Li Danfeng, and then we submitted this particular “rough cut,” so to speak, to Cannes. They loved it, and they said “yes” to us and we really utilized the month of May to really fine-tune all the things that we need to do, post-production-wise, and to really give this film a birth of life towards the end.

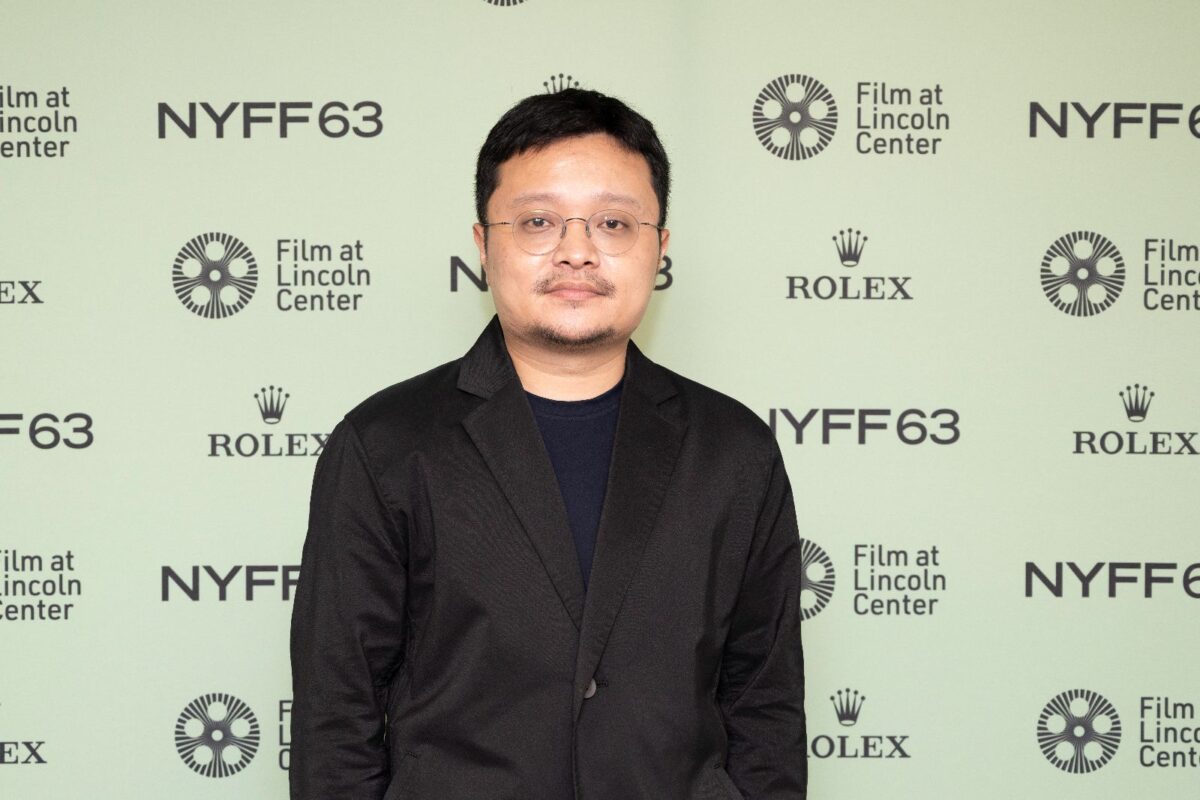

Bi Gan at the 63rd New York Film Festival. Photo by Julie Cunnah.

Has the film changed since Cannes?

There were adjustments done, but it’s sort of adjustments in terms of the intertitles, the subtitles, and making some adjustments in terms of technical aspects of it—to make it even to the point, the degree of perfection that I strive for—and I do think that even from now until the theatrical release in China in November, I will continue to do some minor tweaking to get to the point that I want it to be.

How do you know you’ve reached that level of perfection?

So I do think that the film is done, and it’s because of the very high standards of our visual-effects supervisor that there are certain things that they still want to work on and do some minor tweaking. But for me—for all practical purposes—the film is completed, and then I might do some minor adjustments with the intertitles and with subtitles.

It’s hard to think or talk about the film without the one-shot, 30-minute New Year’s Eve sequence. Watching it, I thought about not just how much effort it is, but the heavy volume of distinct effects moment to moment—gun fires, light explodes, guy gets shot in the hand. I wonder if in the planning stages of these shots, there are conversations with producers or craftspeople who look at it and tell you, “This is going to be very difficult. Maybe consider doing something simpler.”

Charles [Gillibert], one of our producers, when they visited the set and was sort of chatting with one of the crew members in the back, I overheard them talking about, “This Bi Gan style is to really challenge yourself to make what’s impossible possible and make something that’s uncontrollable completely—you can manage it in control of those elements.” Usually the producers, in terms of the content of the film—the creative expressions and choices—they would not interfere and really give me the freedom I need as a filmmaker to make my film. And for the last scene, we were not going to do a long take. In fact, we were thinking about making it into three different scenes for the last part of this elopement at the end.

So we tried to see whether or not it can be told not in one uninterrupted take, but then, later on, realized that maybe we were sort of, as a reflex, trying to not repeat ourselves in such a way that maybe this is something that can be done and needed to be done in one take. We started to rethink our decision not to quote-unquote “repeat ourselves” with this one long take and make it into three scenes. We revisited the idea and the concept of, “Can we tell the story even better with one long take?” In this case, 30 minutes, and that’s what we sort of settled with, and we came to this tacit agreement that that’s what we’re going to go for.

And this is something that is even more challenging than Long Day’s Journey Into Night, because for Long Day’s Journey Into Night, you have one take of one hour representing one hour—the actual filming time, one to one. Whereas for this particular sequence, even though it’s only 30 minutes on film, it took us four-plus hours—from 2 or 3 a.m. to 7 a.m., the entire night, to accomplish what you saw onscreen for 30 minutes. So that’s even more challenging. Not only in terms of this aspect of time—this one-to-one ratio. It’s like a one-to-twelve ratio in order to make this happen. Also the fact that we have to incorporate a lot of genre elements—including the gangster genre, the Hong Kong styles and feel to it with this sort of action coordinations. So a lot packed into this 30 minutes, even though in real time, that’s about four-plus hours to make. It is something, definitely… it’s a mission: impossible that, in the end, we pulled off.

If you don’t mind me asking—hopefully it’s not too personal a question—I have to wonder if the day or night before shooting these long takes, there’s a distinct… tension or nervousness, everybody a little bit shorter with their words. Maybe there’s a feeling in the air of, “Okay, we have to do this, we really have to get it right.” You’d always have that feeling before you shoot, but in this case particularly.

Since you helped me with Kaili, I will be sharing with you my secrets. For me, personally, I don’t really react to either a long take or a shorter take for that particular scene differently. I don’t have insomnia; I tend to sleep very well no matter what, including knowing that I’m going to film this long take the next day. I do think that also now, because of the technology, I get to monitor the scenes very well, and that sort of helps me release the kind of anxiety that I might have. For Dong Jingsong, our DP, I mean, he has sort of been in battle mode for two or three months just for this particular take. So for him, it’s not making any difference whether the night before he’s going to lose some sleep or become extra-anxious, because he’s ready to go; he has thought it through. So that wasn’t a problem.

But for Liu Qiang, who’s my art director, I do think that—and also along with the lighting designer—they have a lot of pressure for the fact that, not only because of the budgetary issues, we need to make sure that we are not going over-budget again, and then also because the cycle is so short, so compressed, that they have to set up everything. Everything is sort of in a very fluid, evolving mode every single day, so they will do all that they need to do in terms of art direction and lighting design in the morning and doing test shots, and then we will rehearse and try to see how we’re going to film a certain take at night. That is sort of the pressure, the pressure point, for them.

And for me, I do think that the only thing that’s different from having a long take and the regular-length takes is that I will always, right before filming the long take, approach the producers to guarantee and assure the safety of my crews, including those crane shots and how we can operate everything safely. Because that’s the most important priority for me—to keep my crew members safe, especially when we film long takes. So I think it’s actually something very intriguing for my crew and my creative teams, including my assistant directors, executive directors, and the reason why it’s intriguing is that for the long takes, actually knowing that they are making that long take relaxing.

The reason for it is because these are the same teams that I have been working with since the beginning, including Long Day’s Journey Into Night, so they are very used to this type of long take and how to pull it off. For them, they are sort of eager to participate in this—almost as if we are a basketball team specializing three-point shots, and that we’ve been holding off on that for such a long time, and finally you are allowed to really end your basket with the three-point shots. That’s the feeling and the energy that we have right before we’ve shown our long takes.

Pleasure finally meeting you. Hopefully it’s not another seven years until the next movie, but if so, that’s also okay.

Two years!

Resurrection enters a limited release on Friday, December 12.