Could a director be best-known for what’s hardly been seen in 30-plus years? Notwithstanding the superb, modernized Hamlet—itself in less-than-prime circulation until a forthcoming Janus Films rerelease—Michael Almereyda is often directly associated with his pitch-black 1994 vampire comedy Nadja. While help is no doubt provided by its association with David Lynch (who personally financed the project and made a fun cameo along the way), the film is a vision par excellence of Almereyda’s mingling formal solidity, veers into shocking experimentation, off-tilt humor, and mastery of performance style.

The film’s also been relegated to a crummy DVD, 480p rips of such, and the once-in-a-blue-moon repertory showing ever since. It’s a true occasion that this distended state—somewhere along the line of which I was lucky enough to write notes for its one-week-only streaming run—ends today with a 4K restoration from Grasshopper Film and Arbelos Films, which releases Nadja‘s three-minute-longer director’s cut at BAM ahead of a nationwide roll-out. I talked to Almereyda (via email) about those changes, this restoration, Peter Fonda’s dual role as Van Helsing and Dracula, Lynch enlisting him for a never-completed project, and his forthcoming Don DeLillo adaptation Zero K.

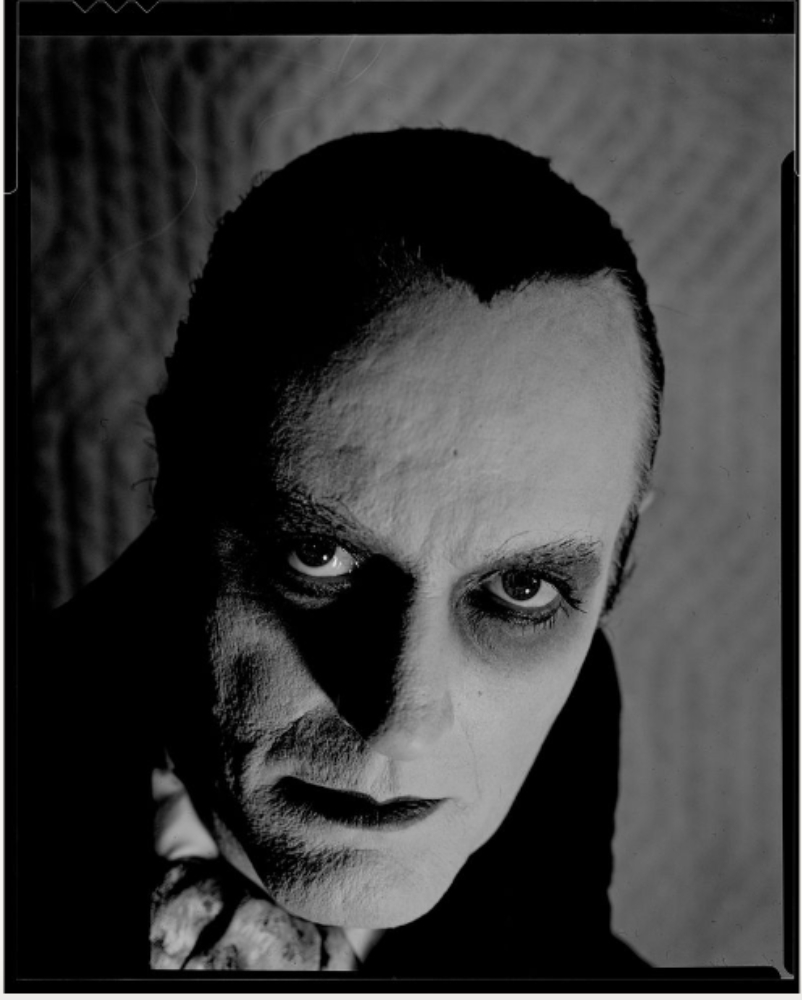

Included herein is a never-before-seen photo from the forthcoming Writings and Relics 1990 – 1995, which Almereyda describes as “a book I’ve thrown together, gathering writing and photos from the early 90s” and is expected to arrive shortly from Sticking Place Books.

The Film Stage: This cut of Nadja is three minutes longer than the initial release. Why was footage cut, and how do you think the movie benefits from their restoration?

Michael Almereyda: Nadja’s premiere screenings at the Toronto International Film festival got pretty strong audience reactions and sparked an offer from the Samuel Goldwyn company that would have doubled David Lynch’s investment. (He paid for the movie out of his own pocket, as I think you know.) But when Goldwyn did a test screening in Santa Monica a few weeks later, the response was considerably less energetic. (I wasn’t there.) In an attempt to rescue the deal, to somehow make the movie more commercial, we made some trims and Mary Sweeney, the lead producer and David’s partner, persuaded Portishead to contribute their music and persuaded me to thread some of that music into the film. This slightly quickened Portishead version, you could call it, screened at Sundance and was eventually released across the land by October Films, after the arrangement with Goldwyn dissolved.

How do you think the movie benefits from the restored scenes?

There was really just one scene that had been cut altogether: Peter Fonda’s Van Helsing stares into a wave machine and talks about love while Martin Donovan looks on. Not a terribly dynamic scene, I’ll admit. A speech from Jared Harris, about the futility of Romanian politics, was also shaved, and a few atmospheric shots of people running were jettisoned or trimmed, as they were perhaps too many other shots of atmospheric running. But thirty years later—actually, I didn’t have to wait thirty years to realize this—I felt that I’d rather see, and share, more footage of Peter Fonda and Jared Harris than less, and I figured that anyone who couldn’t get excited about the film at 93 minutes probably wasn’t going to be seduced by a 90-minute version.

I recall hearing of some longstanding difficulties with licensing the Portishead song used in the film, too. Maybe I’m misremembering.

As far as I know there was no difficulty with Portishead. Mary Sweeney was ahead of the curve, an early fan, and contacted the band before they were quite so famous. She negotiated a deal that bundled three songs, I believe, not just one, and we inserted two. And when David declined to do a music video for Portishead, he recommended me, and there was a sober conversation about a delirious idea I came up with: to shoot on a set with a live lion. The band seemed to entertain this for a while. And then they didn’t.

So this new—or, rather, restored—version gives us more Fonda and Harris, and no Portishead.

I suspect I listened to that album, Dummy, as much as anyone, but I was fond of Simon Fisher Turner’s full Nadja score, which got a bit trampled in the attempt to adrenalize the movie with Beth Gibbons and her colleagues. And, you know, after I failed to make an actual Portishead music video, I thought it might have been a poor trade to turn my movie into a Portishead music video after the fact. In other words: both versions of Nadja are or were the “director’s cut”—I wasn’t forced to insert those songs—but at this late date I prefer the original SFT soundtrack, which breathes more, feels less forced, while also removing Portishead’s specific, emphatic time stamp.

I know that, from this film, you ended up rewriting Lynch’s adaptation of Fantômas. What are your memories of this experience?

I was flattered that Mary and David asked me to take that on. It was an illustrious, potentially massive project originally brought to David by Gaumont, with Depardieu likely to play Inspector Juve. David’s initial swing at it was a fairly direct and unquestioning transcription of the paperback book, an English translation that I’d read when it came out in 1986, from the original serialized Fantômas. (It has an introduction by John Ashbery, wonderfully enough.) But to get to your question: David approved my idea to slide the time period forward just a little, into the late 1920s, to get an overlay of surrealist aesthetics, the look and feel of Man Ray photographs.

And I rushed at the assignment, enlisting a particularly agile and resourceful screenwriter friend named Lloyd Fonvielle, who is no longer with us. We came up with something we were both excited by, with impressive speed, only to have Mary Sweeney explain to us, simply, that David had changed course. He was interested in telling stories that were about now, set in the present and only the present. He never made another period piece. A few years down the road, Alex Proyas somehow got ahold of the Fantômas script and seemed primed to make a grab for it. But nothing came of that either.

What was your involvement with the restoration process? And generally, how did you know this was the true version of Nadja being resurrected, not some botch job? The PixelVision seems like it would be especially challenging. But perhaps MoMA’s print was in great shape.

The restoration was a team effort, with Amy Hobby, the dedicated line producer, and Jim Denault, the DP, weighing in at various points along the way. Yes: the MoMA print was in great shape. It hadn’t been shown much since the film’s debut in Toronto, thirty years back. So I’m not sure what to make of the question about whether or not we were supervising “a botch job.” Arbelos is a first-rate outfit; I felt confident that what was good enough for Sátántangó was good enough for Nadja.

John Cale was originally going to play Dracula before scheduling forced him to exit. Do you recall how the conception of the character might have been different with his involvement?

It was pretty much the same, as scripted: a man with a stake in his heart staggers through the snow, in pain, dying. But I now regret being too careful not to over-reveal Peter Fonda playing the double-role, Van Helsing and Dracula. As the scene was shot with the pixel camera, a good deal of Peter’s performance plays out in silhouette. One of the on-set photographers, Tim Davis, recently unearthed some unpublished pictures, and one of Fonda in Dracula makeup is particularly striking.

I can’t decide if Nadja has more in common with your earlier work, like the outright-comedic Twister or Pixelvision-shot Another Girl, Another Planet, or anticipates the somewhat drier sense of humor and more classical compositions found in later films—it’s probably both. Watching the movie today, do you feel connected to the person who made it more than 30 years ago?

I wish I could say I feel notably different. I still feel like an outcast and outsider and a kid impersonating an adult. Go figure.

You’re doing location-scouting in Brazil for Zero K, a Don DeLillo adaptation that’s been on your slate for several years. How is that process, and what are your general prospects on the film as it prepares to shoot?

I’d like to think it’s going to be the best movie I’ve ever made. Right? It’s too soon to blurt out the cast, but Sean Price Williams will be shooting it and the locations are looking terrific.

Nadja is now playing in a 4K restoration at New York’s BAM ahead of a national roll-out.