In Joachim Trier’s Sentimental Value, a father tries to reconnect with his estranged daughters through a film he wants to make. Gustav (Stellan Skarsgård), a noted director, returns to Oslo after the death of his wife. His daughters Nora (Renate Reinsve) and Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) are reluctant to involve themselves in his latest project.

Their stories play out with Trier’s typical precision and empathy, qualities mirrored by Kasper Tuxen’s cinematography. Tuxen had to find ways to depict Gustav’s earlier films, to recreate the extended takes the director describes in his new script, and to capture mercurial family dynamics among three radically different characters.

Tuxen has collaborated with directors like Gus Van Zant, Ali Abbasi, and Mike Mills. His work on Trier’s The Worst Person in the World received the Silver Camera award from the International Cinematographer’s Film Festival.

We spoke at the 2025 EnergaCAMERIMAGE festival, where Sentimental Value won the Audience Award.

The Film Stage: After The Worst Person in the World, do you feel you’ve established a language with Trier?

Kasper Tuxen: Sure, but that’s also based on Trier’s collaboration with Jakob Ihre, who shot his student films and his first four features. A scheduling conflict made Jakob unavailable when Worst Person was finally ready to go. I credit their body of work before me—that’s part of the DNA of what Joachim likes and what his films are. I think the café scene in Oslo, August 31st is one of the many super-filmic scenes I always bring up while prepping a movie. A reminder of what you can do without dialogue, just camera moves.

In a way, it feels like it’s more important to capture the narrative than establish a style. It’s this realism where, as a viewer, you’re not separated from the material.

I think so. It’s character-driven. Everything is about feeling connected, not removed from the characters. The language that I help in achieving is a mix of something very, very real, but also a love for the traditional craft of film. A fluctuation between formal dolly tracks with long lenses to handhelds where it sometimes feels like you just caught something. Both controlled and on the edge of chaotic.

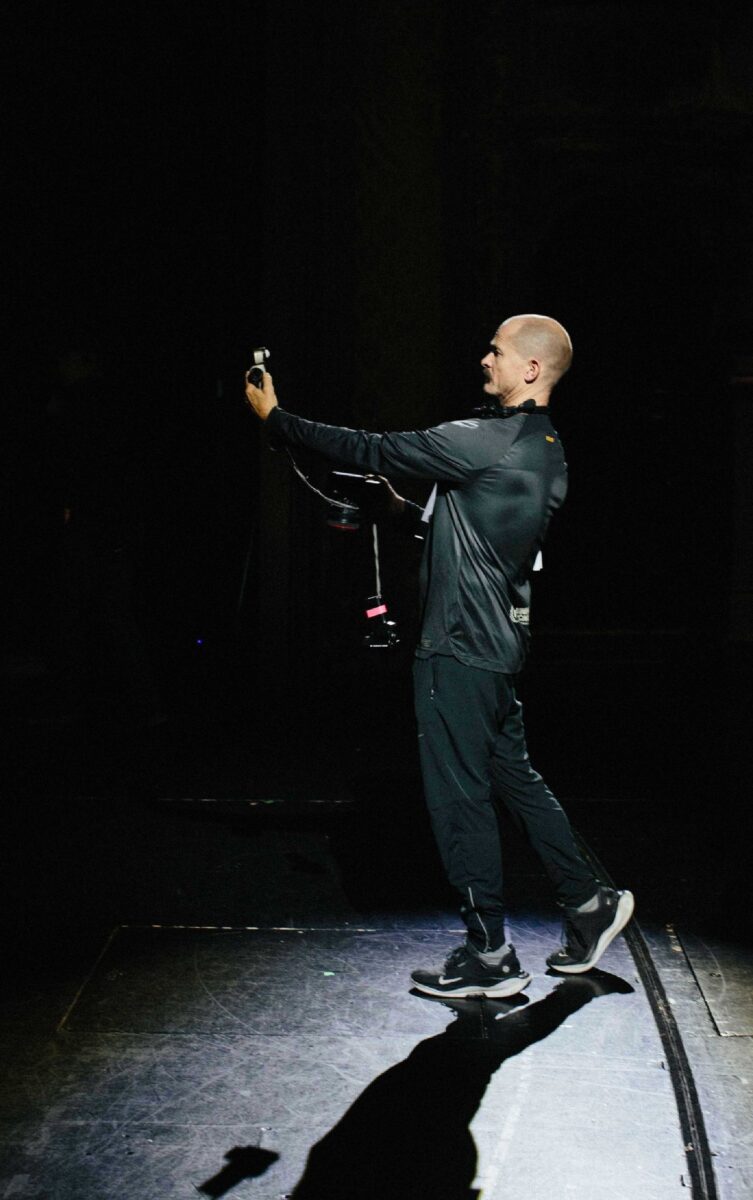

Photo by Mats Høiby / Christian Belgaux

Like the opening scene in Sentimental, Nora’s stage fright at her theater opening. That was some of the most thrilling cinema I’ve seen all year. You captured this unstaged, spur-of-the-moment feeling.

Everything is quite planned and rehearsed. Joachim does many, many rehearsals and adjusts the script after them. I try to be in many of the rehearsals as well, to familiarize myself with the parts of scenes that are between the lines in the script, to understand the challenges that the actors might face, to see all the notes and adjustments. One of the highlights in my field of work is hearing, in this instance, Joachim’s notes to the actors and seeing what the notes become. Between that and all the preparation going up to a take where everything comes alive, it’s up to me to make sure that we see all the work and that we really relate to it.

The theater scene was quite rehearsed. A little troublesome because we were invited into the national theater, where many shows were going on. It was challenging to take their design and set pieces away. We had to go in on weekends to put our sets up, plan some lighting, hang some film lights. We couldn’t just use the theatrical lighting because the blue light backstage wasn’t exposing. We also had our own show we were staging. We actually ended up adding a lot of movie lights, anyway, because the rendition of skin with theater lights isn’t as pretty as lighting for 35mm.

What was your camera package?

We ended up using the same camera and lens package as Worst Person: Arricam LT (Lite) and Cooke 5/i lenses. They’re beautiful. Clean, fast lenses with a little bit of charm. I don’t like adding filtration afterwards. If we want a bit of softness, I think it should come from inside the lens, not a filter in front.

We had a long prep, which gave us a lot of test days to help find looks. We had a contemporary story, but then historical parts that each demanded specific takes as well. Julien Alary, who’s colored all of Joachim’s films, was part of the prep as well.

Going back to that theater scene: did you operate the camera?

I did, but that scene was one of the few occasions where we needed two cameras. My friend Pål Ulvik Rokseth—a great DP who shoots for directors like Paul Greengrass—had some time between projects. He has a history with Joachim, going back to when he was a loader on Reprise. He helped out in the theater scene.

How did you work with Renate Reinsve? She’s got to play that scene on the edge of hysteria. You can’t expect her to repeat takes.

Having now done two films with Renate as the lead, she is so many beautiful things. I cried a lot on both films. I really like to engage, and I guess I’m emotionally available. That’s one of my qualities as a cameraman: I’m a sort of test of how the performance will be perceived by the audience. I think Joachim likes to see if the one audience member closest to the performance is moved by what happens.

With Renate, we know each other well. Some scenes you’re like, “Okay, this is gonna take a lot from her. So be ready.” But she’s also full of surprises in the best way possible. I love being ready to capture whatever might happen. Knowing her energy––I’m proud to be able to tap into that, feel almost like a magnetism where whatever you do, I’ll follow.

What I love about her acting is that she doesn’t care what viewers think. She isn’t worried about how she looks, whether people like or dislike her.

Totally.

Photo by Christian Belgaux

Then there’s Stellan Skarsgård, who gives an extraordinary performance.

I love him to death. The whole cast in the film is amazing, but Stellan is a legend. His body of work—Breaking the Waves, Good Will Hunting, Insomnia. Sometimes as a cinematographer you forget that, “Oh my God, we’re shooting Stellan Skarsgård.”

He is the best. He would never leave the set; he’d sit there on a box and watch. He just loves being on film sets. He even cut his salary so the whole crew could have better catering. He was like this force watching over us.

I loved the scene at his grandson’s birthday party. Did you use two cameras there?

No, one camera. It can be demanding to repeat the scene from different angles, but we wanted to capture the character dynamics. Even if we were able to fit two or three cameras in that room, it’s tough for a director to be concentrating on a close-up while all this other stuff is going on camera B or C. With one camera, you don’t sacrifice any angles. The camera is always exactly where it needs to be.

Single -amera helps focus the performers. It’s like, “Stellan, you play your solo part, and next you’re supporting the others.” You also find out that one actor might be better on take five while another is on fire and needs to go first. You try to arrange the shooting order knowing what each individual prefers, so you don’t burn them out before you get to them.

You said everything is rehearsed, but are there moments that you just catch? I’m thinking of those incredible shots on the beach in Deauville—you couldn’t have planned that weather or those moments.

We were very lucky. It was raining the week leading up to the shoot, which complicated our prep. A few shots in that sequence were improvised. I would say more that planning a lot creates the freedom on the day to decide, “No, we don’t need that shot.” Or, “She’s over there, just go shoot her.”

We’ll have a menu each day that we can put under a pillow or follow if we need to. It’s nice to know we have a shot list but can be free on top of it. We explore that a lot, which is part of what gives Joachim’s work its life and authenticity.

There’s a shot of Skarsgård on the beach where the lighting is incredible and the framing so beautiful. You can’t anticipate that happening.

No. But we’re hoping that what happened would happen. We shot in Normandy, so the sun is actually setting, not rising. We did the sequence over three afternoons and nights, but we had to work in reverse. Late afternoon would be our morning. The ebb and flood tides surprised us one night. We had a Lost in La Mancha moment where we had to move and tents and equipment some 500 meters up from the waterline.

It was a beautiful sequence to make. But it also had that life and super-realism. In Worst Person, we had that whole frozen sequence—obviously very technically demanding. What I love is that when we got to the top of the hill, Joachim was like, “Let’s do some handheld stuff.” We just broke the whole musical setup and went super-real. It was so brilliant, flipping from something so staged to something real. It’s a very powerful strategy.

Skarsgård’s character is preoccupied with creating a long take that goes through different rooms in the house. He acts it out with Elle Fanning, who plays a Hollywood performer who is considering appearing in his film. What I found fascinating is that Trier is showing viewers how directors work.

I think Joachim had envisioned that while writing the script. When we found the location, he was like, “Yeah, this is right. The rooms relate in a way that works with the script, and what doesn’t we can adjust.” He had that shot in his mind when he walked around the house the first time. With very little input from me.

Later, before the cast was involved, we were at the location with first ADs Atilla Salih Yücer, Sunniva Sollied Møller, and Lars Thomas Skare, and production designer Jørgen Stangebye Larsen. So five bodies for the characters. We found the scenes, we found the shots, made the floor plans, filmed everything on an iPhone. Blocking the scenes with Joachim is one thing. When you finally see it with actors is such a joy.

Sentimental Value seems like a deeply personal project for everyone involved.

I actually started a documentary about my parents and my childhood home. I started working on it after Worst Person. So when Joachim came to me with a family house script, it was like, “I’m already doing that.” The paradox of being a part of telling this story while actually abandoning your family for eight months was something that we all had to deal with. Being a filmmaker, you know the sacrifice that this profession does to your life. I think Joachim values that sacrifice. He’s a friend in the process. He’s at home. But I’m far away from my family.

Sentimental Value is now in theaters and available digitally.