There’s always the high-wire act, an exchange-and-trade, attending festivals in enviable parts of the world. Some locations only offer too much joy at the opportunity to kill time with a directorial debut that will never be seen outside these confines. Others are enough to chafe against entire concepts of cinephilia, to engender soul-searching questions such as, “Am I really neglecting this city and culture to watch an ethnographic ‘docufiction’ of 16mm shots of flora and fauna scored by creaky sounds?”

Such questions shaped my trip to Tokyo, likely a dream destination for nearly any cinephile. It’s not only through the Tokyo International Film Festival’s invite that I could see films, attend events, and have enlightening conversations but––after a lifetime of “visiting” the city through mediated images––actually walk its streets, try its cuisines, experience its infamous subways. If not all selections seen over the course of my five days were created equal, most titles made the standard give-and-take palatable. Even in the realm of champagne problems, one understands their fortune while shoring up energy––perhaps with a Japanese Dr. Pepper, which I discovered has 20 flavors contra our own type’s 23, creating a taste that, if not exclusively superior, is evidently smoother and milder––to visit Nakano’s indoor mall or an izakaya on Shibuya’s outskirts.

As detailed in my conversation with Artistic Director Ichiyama Shôzô, Tokyo fills a compelling role: coming at the end of a year-long calendar, its devotion to premieres and newer Asian voices will leaven toxic hype-enthusiasm-backlash cycles so endemic to these environments. The films, more than any festival I’ve attended, just are––what you see is dependent less on personal taste and experience than curated stills, synopses, and the occasional (which is to say infrequent) trailer. If there are certain itches a marquee title can scratch, Tokyo’s room for discovery is higher, its capacity for disappointment lower.

Ergo these selections, which only lack imprint on the English-speaking consciousness for beginning their lifespan in atypically quiet terms. If criticism might double as advocacy, it’s my hope this piece can necessitate what any film needs to endure: further programming, eventual distribution.

I also thought, writing this earlier in the week, I had some unique angle declaring Teki Cometh the best thing I saw at Tokyo, only for it to win a number of their top awards. Hopefully that, more than my own endorsement, propels it someplace else.

The Bear Wait (Hirohito Takino)

This is a solo debut (Takino previously co-directed two films with Quanah Takahata) that often suggests the release of pent-up influence and inspiration. Spot-the-auteur games can prove enervating, and The Bear Wait succeeds to certain ends––E.T.-esque visual treatise on childhood; conjuring an odd aunt-nephew dichotomy; nicely orchestrated shots collapsing the space between physical and spiritual––before it achieves an Apichatpong-like supernatural angle that doesn’t quite manage to undergird drama. Yet the film never loses grip when working through tensions and traumas via text––rather clear signal of post-Hamaguchi cinema, a thought that occurred before Takino very clearly homages a standout shot from 2012’s Intimacies. One can imagine Takino likewise fashioning enough notable work in the next however-many years to become an internationally recognized artist. Special notice to Rei Hirano, star of The Bear Wait and Intimacies alike, whose presence and affect I’d describe as “Japanese Léa Seydoux.”

Black Ox (Tsuta Tetsuichiro)

On the second day of a trip that required 14 hours’ air travel and bred 13 hours’ time difference I sat through this slow-cinema tableaux in which the Marlon Brando of slow-cinema tableaux (obviously Lee Kang-sheng) plays a 19th-century farmer struggles to contain an ox. Black Ox offers roughly as much narrative incident as this suggests; that it only made me nod off twice, likely no more than 20 seconds at a time, is reason enough to commend Tetsuichiro’s feature debut, though that would undercut an eye and ear for dramatic scenarios (such as they are) in this formal context––always easier than it looks, even if the greats never make it look easy. Earns place as a solid entry in the master-shot canon before it climaxes with the rare example of a non-aggravating aspect-ratio change and post-credits gag that splits the difference between thematically resonant and genuinely funny.

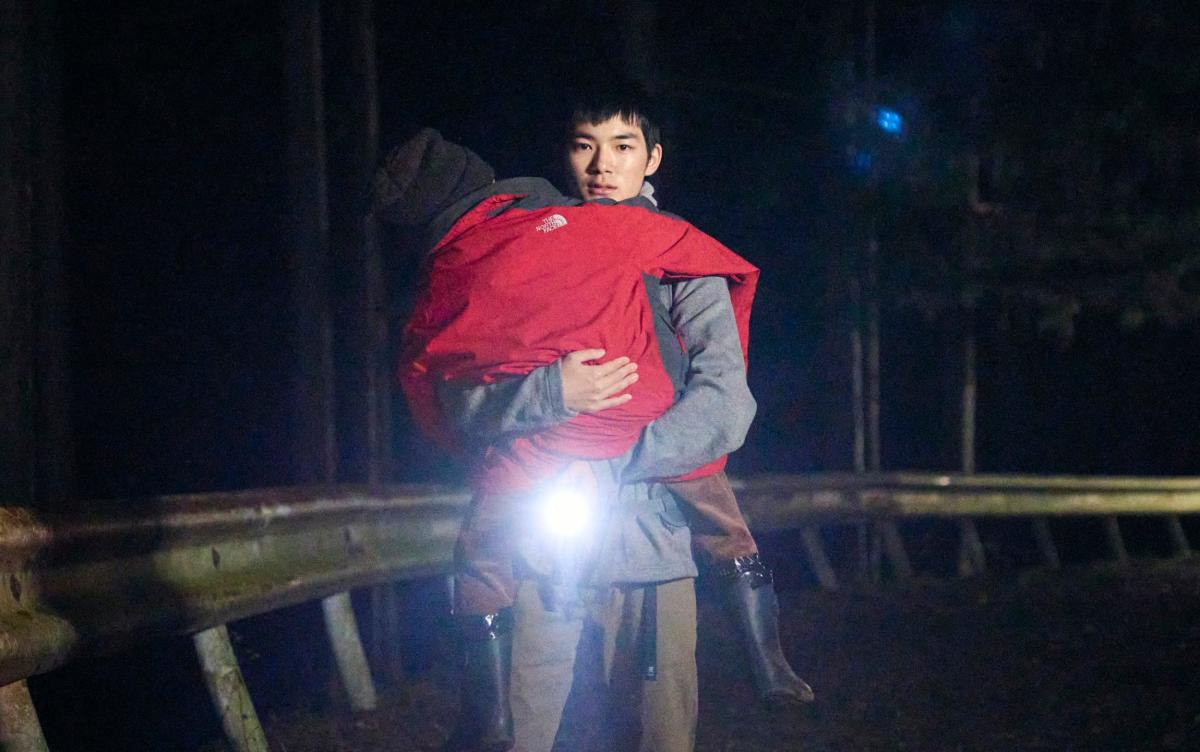

Missing Child Videotape (Ryota Kondo)

A good stretch of Missing Child Videotape might not suggest this placement. Its found-footage angle is clunky as found-footage angles are often clunky––a child experiencing unfathomable terror still manages to frame and zoom his handheld camera in cinematic ways? okay––and attempts at larger mythmaking are neither convincing in the moment or upon reflection. Yet I, who’d draft a small list of things that actually scare them in movies, found myself rather fucking scared during the last stretch of this, which conjures fright from all the items––blocking, cutting, camera movement––often left off a horror filmmaker’s set of priorities. (One bit, somehow unemphasized and never returned-to, yielded this cogent thought: “Ah man that’s scary.”) Does that constitute an endorsement of just the part, not the whole? That stretch stayed with me more than almost anything seen in Tokyo––credit where it’s due.

My Friend An Delie (Dong Zijian)

Before the screening I realized something was amiss. At the margins of my vision (otherwise occupied by the endless neuroses of Karl Ove Knausgård) I realized I was surrounded by festgoers pointing their cameras at me. Or, if not me, then in my exact direction: I’d found myself seated behind star Liu Haoran, who attracts a crowd of size and intensity comparable to American A-listers. If such palpable fandom bred just a touch of skepticism about his onscreen capabilities, My Friend An Delie swept them aside. The feature debut of Dong Zijian (best-known stateside for starring roles in Jia Zhangke’s Mountains May Depart and Ash Is Purest White) well supersedes the common American crop of actor-to-auteur projects, perhaps for being directed by someone who clearly studied A Brighter Summer Day: it evokes adolescence’s emotional maximalism with framing and staging more befitting an epic, and in its contemporaneous segments finds new formal inspiration on a nearly scene-by-scene basis. Continuing a thread of numerous titles seen in Tokyo, My Friend An Delie leaves one hoping for a long timeline on Dong’s directorial ambitions.

Teki Cometh (Daihachi Yoshida)

With respect to all else I saw from Tokyo’s well-rounded line-up, Teki Cometh marks an easy choice for top feature. About 45 minutes pass before its inciting incident-of-sorts––a widowed, financially strained professor receives an unsigned email warning that “the enemy” is coming––prior to which is the pristine, miserable bric-a-brac assembly of its protagonist’s dull life, and from which grows mass degeneration: of logic (this has so many dream sequences that reality or fantasy become indistinguishable from shot to shot), of heretofore rigid austerity, of emotional comportment. A film convincing at either end and, like all my favorites, larger on the inside than it appears from the out. No matter that Yoshida is the longest-active director on this list by leaps and bounds––Teki Cometh was the festival’s true discovery. Any U.S. distributor seeking a sleeper hit should take note.