Having seen and admired his work on several features, I could’ve only assumed that cinematographer Steve Yedlin is well-acquainted with his profession, yet I found myself surprised when digging into his presentation at this year’s Camerimage International Film Festival, “On Image Acquisition and Pipeline for High-Resolution Exhibition.” Fortunately, those who were not in Poland can (and should) dig in with “On Color Science,” an extensive piece in which he runs through the tiny, tiny nuances that create various balances in any given image — and it’s not as simple as film vs. digital.

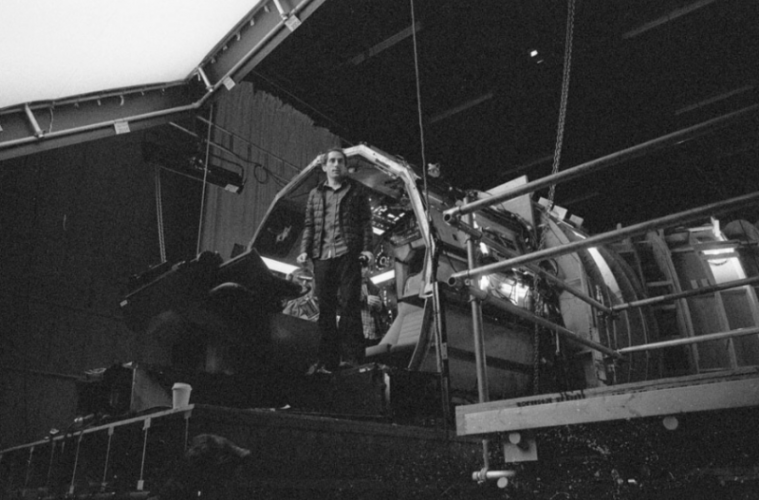

There is, of course, also the fact of his being Rian Johnson‘s regular cinematographer, including a new feature tentatively titled Star Wars: Episode VIII. That is covered in due time, though the broader discussion we were having up to that point proved so engaging, and often so assertive, in its authority that I didn’t want to distract. If nothing else, know this: the franchise has fine minds at its helm for the next (non-spin-off) go-round.

The Film Stage: I’m curious when and how this interest in camera science started. Was it parallel to your burgeoning involvement in filmmaking?

Steve Yedlin: No. It really came out of necessity. Around 2004, I started to feel that digital was coming and it might get crammed down our throats before it was as good as film. I didn’t necessarily think it was never going to be as good as film, but I didn’t think it was at the time. I was worried that market forces were going to force it on us before it was ready. Whether that happened or not, I don’t know, but we’ve gone through a transition and, now, it is ready. I just started digging into what we can do, and it started with the simplest… I remember, at that time, just the simplest, dumbest things being a big revelation. What’s happening inside the camera.

One example: at that time, all the digital cameras were still very much video cameras — even just in terms of having a million switches on them, menus — and there was this kind of prevailing wisdom that was, “Well, it’s a video camera. You have to white-balance. No two cameras are the same.” Part of me was really suspicious. Like, how does a thing even work if that’s the case? If the actual, physical sensor has such a spectacularly wide variance, how can it even work? I know there’s many factoring-tolerance issues, but if it’s that widely different, I don’t understand how the thing cane even function. Sure enough, on the first digital movie I did, Conversations with Other Women, I didn’t have any color science; I was just a DP. I didn’t even know the word “color science” at that point.

The one thing I figured out on that movie was: we had two cameras, and, a lot of the time, we were going to be shooting the same thing — not just for inter-cutting, but split-screen, so it really has to match — and, sure enough, I did some tests. If you turn off things in all the menus, you have to go to the engineering menu and everything, then the cameras do match. You don’t have to white-balance them separately; you can put them at the same setting and they will look the same. It sounds like that’s such a tiny nugget, but that was my very first thing. Everybody thinks that stuff is out-of-control, but it’s just because they haven’t learned it, and it can be brought into control and understood. That was kind of the beginning.

What resources did you have in educating yourself? Did it come down to particular texts and experts?

I talked to people when I could. It’s interesting, because people do ask what I can read, and I wish there was an answer. [Laughs] All of the overall conception things just come from figuring out how to poke and prod at the stuff unambiguously, where you are only changing one thing at at a time. You say, “Can you do this? Yes.” One example is: people superstitiously say, “Well, isn’t it going to look different if you DeBayer it differently?” Well, open up a raw file in NUKE, and do it two times — once with one DeBayer setting, and one with the other, and go back and forth and see what it looks like. Then you’ll know what that difference is.

One thing that happens all the time, that I’ve noticed, is that people jump to an assumption about what a cause of something is — a cause-and-effect assumption, which I mention in the “On Color Science” thing. They make a completely intuitive guess about something they haven’t even studied, and not only do they not know whether that’s the cause — they assume there is just one cause, as opposed to several causes, for something. The example in “On Color Science” is jumping to a conclusion about what makes film look different than digital. Many people have a thing that they’ve decided in their head, and it’s one answer. They’ll say, “Because of a random scatter of the silver crystals,” but can you see that scatter? If the rows and columns of pixels makes it look digital, then as soon as you scan film, it will look digital — because that’s it. You just said that the whole thing is that it’s not in rows and columns, so it would immediately not have whatever this look is that you’re talking about.

People tend to chalk things up to one thing, and it’s a guess. [Laughs] But that’s not just with film vs. digital. That’s with all kinds of things. People guess about what the difference is between compressed and uncompressed. The reality with something like that, again, is complicated. You have certain types of compression that are negligible and don’t matter, you have other types that do, but you get people who are so superstitious. One person will be like, “I can’t shoot compressed!” And it’s like, “Have you looked at what the difference is?” But then someone else will be so dismissive of it that they’ll shoot highly compressed stuff, because somebody told them that the codec is magical, and they don’t notice that it’s actually very degraded because they haven’t investigated. Anyway, I went way off the rails there. [Laughs] What was the original question?

References and sources.

My main source is just to keep going back and doing each element on its own, and checking unambiguously. It’s just kind of checking work and doing things in element. So I always tend to do it. I started out doing most work in Shake, but now I use NUKE. It’s not an ad for those companies; it’s just something where you absolutely, unambiguously can do things mathematically — like, actually type the math expression. It’s not like you’re using some plugin that doesn’t know what it’s doing and just has a knob on it. Anything you can describe with math, you can do, so that’s the main source.

Of course, I looked things up, but I looked up individual things. I end up doing a lot of math for this stuff, but I’m not actually good at math, so I might end up looking up how to do a point-line distance in 3D space. Looking at individual things or very technical things. Sometimes I might be looking at the ARRI scanner manual — not because I’m using a physical scanner, but because they have some information in there — so there isn’t really something that teaches, overall, that I know of. There are color science books, but I actually haven’t read them, and those are targeted at overall color science — which isn’t even specific to cinema. There’s a guy called Garret Johnson; he’s the color scientist for Apple. I think he still is. I kind of got to know him, but that was years ago, so I lost touch with him. I think he was and is the only color scientist for Apple, with a PhD in color science, and he has a book that’s one of the more-known textbooks. But I haven’t read it. [Laughs] This stuff, it doesn’t concentrate on this type of application of the concepts.

You gave what seems like a similarly focused lecture last year. I wonder what experiences, if any, might have changed the shape of it.

Last year, I showed the demo that you’ve seen online and basically just talked about it. This year, it’s a new demo that’s similar to the other one with the same, overarching philosophy, but it focuses on resolution instead of on color and texture. It’s in two parts. The first part is the demo as it stands right now; the second part is… there is going to be a second part, hopefully, [Laughs] where you watch one and then the other. But the second one doesn’t exist, so, right now, the second one is me giving a presentation. It is totally different, just in the sense that it’s not the same thing. In terms of how philosophy… I don’t know if the overarching philosophy has changed since last year, but I’m always learning. I have a lot more details. Always digging deeper, so I’ve got more details — more exact answers to questions. I think that’s the biggest way that it’s different.

Honestly, to me, the new demo is a much more boring topic of resolution, because we should just be past this. Who cares about counting pixels? The short version of this demo is, “Why are we counting pixels?” I think it should be the more boring one, because I don’t even know why this is an issue, but the fact that it is an issue is why I had to make it. Having gone through the steps of it, I have verification of things. It’s things that I’ve known, that I’ve seen viscerally. I was talking about people guessing about things. It’s things that I’m not guessing about, but I don’t have years to explain to people what I’ve seen that proves it. So this is like, “Here it is” instead of me trying to explain technical stuff that I’ve investigated over many years. “There it is. Have a look.” [Laughs] I think the new demo has stuff that’s not its topic that’ll be interesting.

The new one is very pointedly where I say, “Look, the point of this thing is to say, ‘Why are we counting pixels?’” I’m almost dismissive of having matched these different formats — two are film and four are digital — and they don’t look exactly the same, but I don’t think, like in the other demo, there’s anything that stands out as being something that makes one look a recognizable way. They’re just very, very slightly different. You don’t even know which one’s which, and you couldn’t probably pick out… well, there’s one you might be able to pick out more reliably than the other five. Although I like to be very clear and concise — “here’s the topic,” and all that — I think this one, more than the others, does have some stuff that’s implied rather than stated. It’s only about resolution, but I think it’s going to raise questions about optics and other things. Partially, just seeing this vastly different-sized sensors next to each other, and the differences that you don’t see. [Laughs]

With all these applications and variations in mind, how does shooting a Star Wars movie come into play? The series has such a powerful iconography, and I wonder if you’d actually relish the opportunity to shoot this film in a way people sort of expect — because there’s some fun in that particular opportunity.

You know, Rian and I just approach it the same way we approach everything. There are aspects that… we talked about it very cursorily at the beginning, but I think we’re on such the same wavelength that that’s all we needed, was that little talk just to make sure we were on the same page. I think we said, “Enough of what we do, anyway, fits the bill.” Anything that we want to do… we didn’t have to do anything, so there were aspects where, to some extent, we wanted to have a continuity; and, on some, we were just doing what we’re doing. I think because I know Rian so well, it was easy to agree on that and know what we both meant without checking. I can imagine doing it with another director, where you say, “But, wait… what do we mean?” Even a smart director. It’s just the communication: Rian and I have known each other for so long, and I know what he means, and he trusts me.

I assume you’ve developed such a shorthand at this point. I’m curious if it’s more and more, almost to the point of telepathy.

Yeah, maybe. In some ways, I do think that. It is fantastic with him, and I’ve never had that close of an understanding with a director — even from the beginning — and, of course, it’s only gotten way better. I still don’t feel like it’s telepathic, but I’ve had people say that it feels like that. I mean, even on Brothers Bloom, people would say, “How do you know what he’s talking about?” He’ll just say, like, “The Miller’s Crossing thing,” or something, and I know which shot he’s talking about and why he’s mentioning it, and he only means this one aspect of it.

I think some of the ways that the communication has changed has more to do with how Rian’s style has changed. We had already done so much together, even by the time we had done Brick, because we had done all these short films and student films together. We’ve always had a great communication, and it’s evolved as his style has evolved. I always thought he was just a master craftsman. It might sound hyperbolic, but I feel like he’s an Orson Welles or a Kurosawa — he’s just a master of the cinema language, and he’s just gotten better and even more amazing. But how he does it has shifted slightly — not his personality, but the methodologies. I just kind of shift along with him.

He’ll cite movies as the key inspirations for whatever he’s currently working on. Do you contribute to that list, or even talk about them?

No.

Is he more the voracious viewer? Do you watch a lot of movies?

I watch a lot of movies, yeah. I’m not nearly as literate on it as he is, but, yeah, I do watch a lot. He doesn’t usually talk to me about stuff that way. [Laughs] I think one thing that we always had in our communication that’s gotten even better is… I personally think that too much talking about references is a waste of prep time. It’s one thing to talk about something briefly, but it’s not going to literally be that thing. Which aspect are we talking about? If you can spend prep time making sure you’re on the same page on these really vague, coarse, overarching things and then spend the time actually prepping what you’re going to do, you’re using your time so much better.

Also, in prep, he gets so busy. Prep itself is a limited amount of time, and then there’s an even more limited amount of time when I can talk to him about stuff. If I can be bringing him questions that aren’t, like, from a place of emotional neediness, but, “We’re going to put a lamp on a chain motor right now”… very practical stuff makes a bigger difference in the actual storytelling. I think that’s one of the traps: we are doing storytelling. I think there’s a sense that talking about things in emotional, literary-theory kind of terms is helpful, because then we get down to the storytelling. he thing is, we’re telling a story with light and cameras and stuff, and the bottom line is, each one of us is going to do our job. You can have all these emotional discussions, but then, the bottom line is, the part that’s cinematography — how are you telling a story with light? — does come down to where are lights, and what does the light look like.

If you can make sure you’re on the same page with that big stuff and then focus into the actual storytelling, even scene-by-scene rather than talking about the look of the whole movie — even to say, “In this scene, there’s light radiating out of this thing”; whatever it is — if you can get down into that… Rian has amazing ideas for the story side of lighting. He’s very hands-on with camera; he knows exactly what he wants with shots. With lighting, he’s very hands-off — in terms of, he knows I know how to light it to make it look good. But, conceptually, he’s very hands-on with lighting. Even, sometimes, a scene will be built on a concept of what’s happening with the light. He doesn’t have anything about how he wants me to do it — he’s not making me do it a certain way or anything. [Laughs] Even in Brick, the Pin’s basement: he knew from the time he was writing the script that he wanted those lights behind the Pin, where it’s shining onto Brendan, so he wanted those lights on the wall and a murky, florescent light overhead. So that’s a story thing — how that’s executed and all that. We’re not even discussing it.

Are there certain things you really crave as an artist, in terms of freedom within a collaboration?

I don’t think you can; it’s such a collaborative thing. If you set out with a rule about it, I don’t think that’s ever going to work. The director is the boss, and if that’s something that they would want to put their hand in — if you somehow put up a wall and say they can’t do it — they’re the boss and ti’s a collaborative thing. I’ll admit that there are things, with certain directors, where I wish they would let me do it; not really with Rian so much. But that wouldn’t just be in one little area. You know what I mean? I wish, in this area, he would just let me do my thing, because this isn’t making it better. It’s taking time and it’s not making it better, and we really can do this correctly. [Laughs] I think, overall, the process works pretty well. So yeah, no, I definitely don’t have any rules about it. If I feel, in a meeting, that this might be somebody who does want to control an area in a way that I don’t think is good, then I might not do the job. But, yeah, once you’re doing the job, putting up walls is not a very collaborative way of doing it, and it’s making it harder for yourself. If you come off as an expert in a certain area, then people want your opinion on it.

I like to think this is the absolute opposite of the worst question I could ask you, i.e. “What is Episode VIII about?” I’ve always sincerely wondered this about someone in your position: is it funny to know every inch of this movie that is such a secret? You’re there every day, for every shot, and then you can go on so many websites to find endless speculation. Is that a funny part of the job?

You know, honestly, that aspect of it really doesn’t… I don’t really look on those message boards and stuff. The thing is, I’ve been a huge Star Wars fan, but there’s nothing that I’m a fan of where I’m interested in speculating. I don’t even know what the point is. You go to a movie and you want to enjoy it. What’s the point of… you know? Just watch it and see if you like it. The other thing is: if there’s a spoiler that ruins the movie, that’s not a very good movie. If just knowing that something happens in a movie ruins the whole thing, that’s not a good story. [Laughs] There’s a reason that the great stories aren’t just a big surprise. It’s not just a big twist at the end, like, “Take off the mask and reveal.” None of the best stories are that. You even look at Vertigo, which is the epitome of the “surprise movie,” or the twist, but the twist happens, what, half an hour in?

You can’t only think about that in plot terms, of all movies.

Exactly. If knowing something about the twist ruined that movie, that would not be a good movie. It’s pretty amazing the first time you watch it; it’s more amazing when you watch it again. And that’s a movie that’s about a twist. I don’t know why people want to speculate. I mean, I guess I understand it “psychologically,” but I don’t understand it as a cinephile. I understand it just, generally, separate from the idea of narrative in cinema. If you’re actually into cinema… [Laughs]

I would love if that answer shut down the whole industry, but…

No, that will definitely not happen. Honestly, I just really want to see the movie. Separate from having worked on, I’m just really excited to see it. Knowing what happens does not make me any less excited to see it. [Laughs] I’m very excited.

Have you seen sizable portions in post?

No. I haven’t seen anything yet. I saw dailies, but I haven’t seen anything cut together.

See our complete Camerimage International Film Festival 2016 coverage.