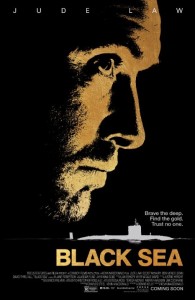

Kevin Macdonald‘s Black Sea, which hits U.S. theaters this week, features top-notch acting and, like the submarine, is air-tight, but music is also another highly effective component to the thrilling story. In addition to pulse-pounding sounds and pensive themes, British composer Ilan Eshkeri also adds a thick layer of humanity to the story about about greed, hard metals and icy depths.

Best known for his film scores to Stardust, The Young Victoria and Kick-Ass, as well as his collaborations with recording artists and his concert work Eshkeri’s career is notable for its diversity; recently Eshkeri scored Still Alice starring Julianne Moore, Alec Baldwin and Kristen Stewart, 47 Ronin starring Keanu Reeves, and Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa starring Steve Coogan.

Eshkeri has collaborated with recording artists, including Tim Wheeler from Ash, Smith & Burrows, Emmy the Great, Tom Odell, Coldplay, David Gilmour and Annie Lennox. He has worked with Amon Tobin on a live orchestral performance of his work, wrote The Young Victoria song, Only You, for Sinead O’Connor, worked with Take That on the film Stardust and has been commissioned to write for the world-renowned pianist Lang Lang.

We hit on many high points in his career, so enjoy our session with the amazingly diverse Ilan Eshkeri.

The Film Stage: Black Sea is thrilling to say the least. I honestly haven’t felt that tense and claustrophobic in a film in a long time, and your music went a long way in achieving that.

Ilan Eshkeri: That’s great! [laughs] Well then, that was job well done by Kevin, me, and the rest of the crew. [laughs]

One of the standout themes is right at the very beginning with “Leaving Sebastapol” and your string work is just sensational, even before the guys ever get in the boat. Kevin Macdonald, in our recent interview, talked about not wasting any time getting them on the submarine. Can you talk to us about the differentiation between the orchestral themes and the more makeshift and ethereal instruments when the characters are underwater?

Actually it was the makeshift instruments where things got started. Kevin didn’t want a very traditional score. When we come to the end of the film, we get a little more orchestral but I started trying to find sounds that were related to the world that they were in.

Actually it was the makeshift instruments where things got started. Kevin didn’t want a very traditional score. When we come to the end of the film, we get a little more orchestral but I started trying to find sounds that were related to the world that they were in.

So I looked at banging bits of metal and making creaking sounds, and things that made you feel like you were underwater. So I got an old beaten up steel drum, then I got some other pieces of metal that we banged and put in a sampler, then later I played a lot of sounds on a violin.

I was a violinist many, many years ago, and not a very good one, [laughs] but I made a lot of scratching sounds on the violin one night then put them in Pro Tools and changed the pitch and the timing to be these real low sounds. Sometimes, some of those sounds with the strings were things I made up using layers and multi-tracks. That was kind of fun because I was a doing a mad scientist kind of thing – using these random instruments and me scraping the bow across the violin.

So that was the initial sound world we came up with. Also, rhythmically, there’s a lot of stuff that’s in 5/4 which is, instead of four beats to a bar, it’s five beats to a bar which makes it kind of uncomfortable. For example, telephones ring in 5/4 and it’s an alarming sound with an uncomfortable feel to it. So I thought of all these ways that we could make it feel uncomfortable.

Then we added a brass section, a pretty large one actually, that plays up these more epic moments when the submarine is under the water. They had these big weighty chords, and then, inevitably, we had the strings. They are the most common element in the language of film music and the audience accepts strings in every scenario to help carry the film. But we recorded the strings and the brass separately because, obviously, the brass would have been too overpowering to record together with the strings.

It seems, to me anyway, that the earmarks of a great composers are how well they use strings. There’s great work here and you also got a lot out of your players on 47 Ronin which is another one that’s really well done.

Thank you. I guess I have a bit of a head start because, as I said, I was a violinist so I know a lot about how strings work. [laughs] But in just the last couple of years I’ve been working with string players and have been learning a lot of things I didn’t know, and that’s what’s fun about the orchestra and all of music really. There are infinite combinations of rhythm in music and harmony, and that’s really inspiring to me. So when you get to a film like Black Sea with a director who is encouraging you to find new things, that’s great because they’re giving you the opportunity to be creative.

One thing Kevin Macdonald and I talked about was the pace. In a film like this, things can only happen at a certain speed. When the characters are on the seabed – which is the most excruciating part of the film – you just know something bad is going to happen. How does the pacing of the film affect the music, especially when you have to score that kind of slow-motion terror?

I think that is one of the things that is difficult about a film like this. You don’t want the film to get slow, or boring, but at the same time you can’t put push too hard because it would seem incongruous. In modern filmmaking, people are very concerned about pushing the audience through the film as fast as possible. With Black Sea, we tried to find the right moments, where we could push and give it extra if needed.

boring, but at the same time you can’t put push too hard because it would seem incongruous. In modern filmmaking, people are very concerned about pushing the audience through the film as fast as possible. With Black Sea, we tried to find the right moments, where we could push and give it extra if needed.

In all art forms there’s a lot of trickery, or magic, where things feel a certain way. But actually they only feel that way because of what came before them, and what came after it.

With the seabed stuff, when the characters first step off the submarine, it’s incredibly still and I wanted to have the sense of sound design, like stepping onto an alien planet. I like this idea that the weight of sound is felt through all the speakers around you in the theater and that you feel the pressure of the water.

That, I feel, is very nerve-racking and then the music picks up quite soon after. Once they start walking it can pick up. It has the illusion of wading through something thick, but if you listen to the music in isolation I think you’ll see that we push quite hard through there. There are various tempo changes and we start moving faster.

One other thing about that area of the film, sorry if this is a little nerdy [laughs], but there’s this piece of music called La Mer, which means “the sea” in French, by Debussy and it has this kind of stormy feeling to it with the cellos and the bass which I quoted a couple of times in the score. It’s this slightly uncomfortable rhythm but it has this feeling of something lurking, it captured the weight and the power of the sea and I really wanted to use that.

But in that bit where they go underwater, I created these notes that were comprised of the nooks in that motif. I played them all on the violin, layered them up, put them at different pitches so that you had this seven note chord that just permeates that whole scene all the way through. I liked that it was rooted in another sort of classical piece about the sea.

[laughs] That’s not nerdy at all. That’s why I love talking to composers, hearing those behind-the-scenes stories and decisions that makes themes and cues so compelling and indelible.

You’re developing a story and a character with music that adds to the film, and I like to go into the movie knowing that in advance. In fact, what I do, and this is probably considered equally nerdy, I actually listen to a film score four or five times before I even get into the theater because it makes the movie feel a little more full once I know the auditory story you’re trying to tell.

Well you should listen to it. I’m about 90% certain it’s the fourth movement of “La Mer” and you’ll hear this little rest and you’ll see that I quoted it. For me, it’s very important at the start of the film, and it was with this film as well, that I create a rule, or set of rules that I can work with. You know, sometimes you can get blank canvas syndrome and you’re like, “well I could do  anything,” and it’s terrifying when you don’t know where to start. But if you make up guidelines and tell yourself “okay, I’m going to do this,” like if you were an artist who was only going to paint on miniature canvases, then suddenly you have a rule and a way to go and something to push against.

anything,” and it’s terrifying when you don’t know where to start. But if you make up guidelines and tell yourself “okay, I’m going to do this,” like if you were an artist who was only going to paint on miniature canvases, then suddenly you have a rule and a way to go and something to push against.

It’s like that expression, ‘there’s no art without resistance from the medium’ and I believe that. So with Black Sea, I made myself a set of rules about the metallic stuff and the uncomfortable rhythm and so I used this thing called the optotronic scale which is whole tone/semi-tone/whole tone/semi-tone. It’s symmetrical, and it almost sounds like it’s diatonic but it isn’t, it’s just a little bit uncomfortable. So it was about finding these tools I could use to make it feel unnerving.

Once you have all those rules in place, you can break them and then do whatever you want because ultimately you’re just trying to make good music and tell a story. But like I say, it’s nice to have something to push against. I like that it gave a very mathematical and machine-like feel to it which made sense in the submarine, but you couldn’t use that all the way through. I needed something a little more emotive because I had to play up Jude Law’s character. That’s what we call the family theme, and was something a little more emotive. It happens at the beginning and then at the end because, really, he is driven by love for his child and trying to make a better life for his family.

Exactly right, that’s actually what I was glad to talk to Kevin about – this is a heist film, but it’s not greed driven. The impetus for Jude Law’s character is to make up for him not being there for his family. You do need that heartbeat among all the clanging metal.

Yeah, it is nice to have those contrasts and I hope it comes through as well. Another big contrast was the theme for Fraser, the crazy guy played by Ben Mendelsohn. His music was something I wanted to make it feel like a ticking bomb, like he’s just going to explode at any moment. His music starts slow and gets faster and faster until it gets so fast it becomes this big bit of noise. That happens the first time he kills one of the characters and happens again later on.

Macdonald has a history of making films and documentaries, but let’s jump quickly to Coriolanus which is Ralph Finnes’ directorial debut. Working with someone whose career has been in front of the camera, what kind of conversations did you have with him now that he was being immersed in actual filmmaking? Was there anything that maybe you taught him about how the process works from your perspective?

I think we learned a lot from each other. Ralph was very nervous about music. He didn’t want much in the  film, and I think that because he’s such a powerful actor, and such a brilliant performer, that he felt like it’s all in the performance and that the film didn’t need music to tell people how to feel. We had some funny times listening to loads of music and he didn’t like anything. It was difficult. So I think he was nervous, he would say to me “what’s wrong, it’s all fine as it is.”

film, and I think that because he’s such a powerful actor, and such a brilliant performer, that he felt like it’s all in the performance and that the film didn’t need music to tell people how to feel. We had some funny times listening to loads of music and he didn’t like anything. It was difficult. So I think he was nervous, he would say to me “what’s wrong, it’s all fine as it is.”

I remember one time he suggested “okay, maybe we have a drum”. He had this idea that everything had to be real and part of what’s on the screen so he would say, “okay, in this scene I walk in, and I say this thing, and maybe there could be this drum that goes ‘bwoof’. Then I say this speech, and then I leave, and everyone is left standing there, and another drum can go ‘bwoof'” and I was like, “yeah, yeah, we could do that.”

But then I had this idea and I said “you know Ralph, because the character of Coriolanus is a soldier, what if we use the trumpet?,” and as I said the word trumpet I could see pain in his face, and I quickly said, very explicitly, “No, not a melody! No, not at all. Don’t worry, just the one single note, like quintessence of trumpet, just the concept of trumpet. One lone note, that’s it!”

And that was a crazy enough idea for him to say “okay, I could see that.” And we had trumpets in the score, but literally, only playing one note at a time here and there. I think I counted once, just for Ralph’s amusement. In the entire score there’s 20 notes of trumpet and that’s it. But it ended up being really quite effective because it was exactly that, just quintessence of trumpet and it never became more than just one piercing note. It was very minimalist, but also very powerful.

Not to say minimalist, but rather it’s similar to what Hans Zimmer did with the Joker’s theme in The Dark Knight. That one unending string note makes such a statement that the score doesn’t need a 12 minute suite for the character. It can be indelible with so much less.

Yeah, that was so great. I think it was made up of a few things, but that one kind of rising sound for the Joker was something that really set you on edge. It was a really brilliant idea that. Also it was one of those things where the performance was so powerful and so insanely brilliant that it didn’t need much music. I think Hans really found the exact right bit of music that supported the performance in the perfect way. It was so simple and brilliant as all the best ideas are. I love that as well.

Let’s briefly hit on Fleming: The Man Who Would Be Bond. I guess many composers grow up saying “One day I want to do a James Bond movie, or a Star Wars movie.” What was it like working on something that was tied to the lineage, but not exactly a true James Bond film? I really, really liked that by the way, both the narrative and the music.

Honestly, it was not as you described it, that opportunity to write a great James Bond or Star Wars film theme. It was more understated than that because it was about Ian Fleming and his experiences that led him to write James Bond and I wasn’t looking for the opportunity to do something completely huge and fantastic. It was, however, extremely fun to do something that I wrote with my good friend Tim Wheeler, who is a rock and roll artist, and we collaborated with another mutual friend of ours Mat Whitecross, the director.

On a personal level, it was super good fun for us to work on this together, and musically, of course, we took a lot of inspiration from John Barry and it was very nice to explore that style of music and bring in elements like that.

But with the other stuff, like string quartets for instance, it felt like we brought some really interesting music to the project and we got a lot of great guitar performances from Tim as well. [laughs] It’s funny, no one’s ever asked me about that, so I’m glad that you watched and enjoyed it. I almost forgot I did that. [laughs]

Picking up on what you said about collaboration, Kick-Ass is your third time working with Matthew Vaughn right? It’s confusing when you see that more than one composer worked on a film. So what was it like with four of you? I got to speak to Henry Jackman recently, but we didn’t have a chance to touch on the film.

Oh man, Kick-Ass was so complicated. Originally, the concept behind the music was to not have any score at all. At the beginning, when the guy jumps off the building, the whole point of it was to have the Superman theme there and later, when the character of Chris (played by Christopher Mintz-Plasse) shows up, it was supposed to be to the Batman theme. These two characters were trying to be like characters they read about in the comics.

Matthew and I spoke at length as far back as when he had the initial ideas for the film. Originally, he had planned for Marius De Vries, who was famous for doing Romeo + Juliet with Baz Luhrmann and who is very good at adapting songs, to come and adapt those songs to the point where there was no score at all in the film.

But as it developed, ideas changed for all the millions of reasons that things change during the creative process. So Matthew brought me on board and it was great because I started working with Marius who was a pal of mine, and it was great that we’d get to work together.

But there was other stuff that was up John Murphy’s street, and Matthew had worked with John before so we decided to bring him in to help. Now the schedule was really difficult so Henry Jackman came in towards the end of it and he did some really brilliant work. He’s a great composer, and I feel like he was just breaking into the scene then, and has done such amazing work since. The four of us just got on like a halcyon fire; we were at each other’s recording sessions, helping each other out, sharing themes, and it was fun times really. It was unconventional but it worked and we made a great movie. Really, it was a good experience.

You guys have gone on to do such great work individually since then. But tell me, that brass in the main theme, was that you?

[laughs] Oh you can’t ask me that, that’s giving the game away. [laughs] I think the only fair thing to say is that it was a collaboration between all of us.

So you guys were like a band?

Yes, I think so. I don’t know what the other guys would say if you asked them, and I would never want to take credit for anyone else’s work, but the way I feel about it is that we all did it together. So it’s best that we are perceived as a band, rather than any one person trying to take credit for stuff. [laughs]

Got it. Now there’s something else I’ve always been curious about. When composers start the spotting sessions, do you ever plan to put a little more emphasis on the theme when you know your name is going to come up in the credits?

[laughs]

Maybe it’s just coincidence and timing, but I’ve seen more than a few instances where it seems that the music rises just a bit when the composer’s name is on screen at the beginning of the film.

[laughs] You know, if I had the opportunity to do it, I probably would. [laughs ] So often, it doesn’t work that way. But to be honest, for me, the arc of the film is important whether it’s the titles at the beginning or the end of the film. It’s much more about making a piece of music that really works that takes the audience into the film.

Of course, we make jokes all the time like, “I thought there was going to be gold around the letters of my name! That’s it, I’m going to put a really bad tuba note when it comes to your name!”[laughs]

This is been really great chatting with you Ilan, thanks very much for your time. Before I head out, I have one more question.

Please!

Howard Blake. How do you even attempt to follow up The Snowman?

Oh my God. How do you even know about that? That’s a British thing!

I grew up with it actually, and first saw it when I was maybe 12. My dad worked for Sony and, I guess, during format testing, he brought home one of the early camcorders. With it, he brought home some titles like Beetlejuice and The Snowman on those little Video8 tapes and I just fell in love with the story. Now I know of the David Bowie intro, but I grew up with the version where the guy, the grown up kid actually, walks through a field and says, “I remember that Winter, it brought the heaviest snows I had ever seen”.

Anyway, when I was looking to buy The Snowman on vinyl, I kept seeing listings for The Snowman and The Snowdog and I’d never heard about it until about November of last year.

Have you seen the sequel?

No, not yet. That’s why I was hoping to get a little bit of info from you.

If you don’t mind, I don’t have a short answer to your question because it is something very close to my heart and really important to me. But I’d still love to tell you about it.

Sure, we can follow up later this year, turn it into a whole conversation maybe closer to Christmas. But please, if you’ve got a minute, go for it.

Well they started making the sequel, and they called me in because they knew I collaborated a lot with rock and roll artists and I had worked with Coldplay and people like that. We had this big conversation about updating The Snowman. The sequel takes place 30 years later. They thought that if it was a more modern world that they need a classic score but also that the song needs to be more contemporary.

Well they started making the sequel, and they called me in because they knew I collaborated a lot with rock and roll artists and I had worked with Coldplay and people like that. We had this big conversation about updating The Snowman. The sequel takes place 30 years later. They thought that if it was a more modern world that they need a classic score but also that the song needs to be more contemporary.

And so we talked about different artists and so I said “look, if we have a huge artist, it becomes more about them than it should be, and it needs to be about The Snowman.” So I played them a few up-and-coming British artists that I loved. One of them was a friend of mine named Andy Burrows who used to be with the band Razorlight. He’s a brilliant songwriter. We brought him on board and that was the team. Andy and I decided that we’d collaborate the whole way through. Obviously, I have my strengths and he has his, but we wanted it to be a collaboration and we worked on the song together and the score together.

But your question, how do you follow Howard Blake? I grew up watching The Snowman every single Christmas my whole life, and so did Andy. So it was terrifying thinking about touching that. We said, “we can’t be be better than The Snowman, we just need to approach this with honesty and the love that we have for the original, and put that into the sequel and then hope to God that people take to it.” When you watch something every Christmas of your whole life, you kind of take ownership over it at some point. My real fear was that people would feel like we ruined The Snowman. I remember that when talking about it. We had the idea that as long as people don’t think that what we’ve done is completely shit, then that was okay. That was our motto – Do your best, just not shit! But that element of it was terrifying. It was really scary.

I’m really proud of what we did. It’s been a success and it was even released on vinyl which is the first time that’s happened in my career. We’ve also played that live to picture at Christmas concerts where we have loads of friends perform all of our favorite Christmas songs at the interval – Muse’s Dom Howard, Ash’s Tim Wheeler, Tom Odell, Mel C from The Spice Girls and all of our friends. I hope we continue to do it. It’s definitely one of the things I’m most proud of.

Still Alice is now in theaters and Black Sea arrives on January 23rd. For more information, and to listen to samples of his work, head to Ilan’s official website and follow him on Twitter at @ilaneshkeri.