One of the most anticipated films in the newly established Competition section at this year’s Busan International Film Festival was Resurrection, an epic look at cinema history from Bi Gan.

For almost three hours, his Cannes Jury Special Prize winner Resurrection explores 100 years of film, from silent comedy through film noir, thrillers, sci-fi, and romance. Glimpses of everything from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari to The Lady from Shanghai emerge in the story, which is set in a world where dreaming is outlawed.

German expressionism, Sergio Leone’s monumental close-ups, David Lynch’s body horror––they’re all here, along with Bi Gan’s exhilarating extended takes and spectacular locations. Taiwanese diva Shu Qi shows up in an outfit straight out of a D.W. Griffith melodrama. Jackson Yee, China’s reigning heartthrob, plays several roles as a “Fantasmer,” a shape-shifting dreamer who can disrupt time.

Resurrection culminates in a breathtaking half-hour shot that takes place on New Year’s Eve before cinema seems to end in a theater of melting wax.

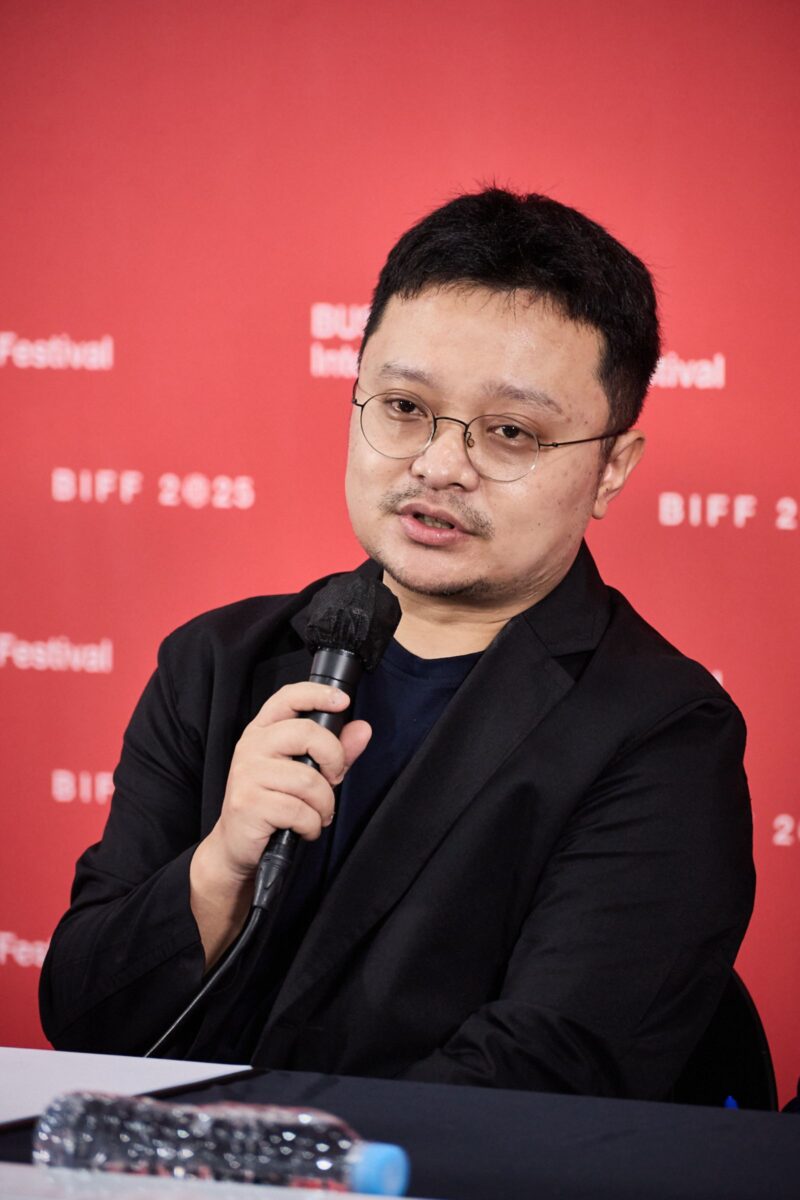

“Dreams are crucial for humans,” Bi Gan said at a press conference the morning after the screening. “In ancient times, before electricity, before fire, there was only dark at night. That gave the ancients more time to dream. Through dreams we get our visual imagination. They help our eyes develop. The elements of dreams are precious. Film can be as important and precious as our eyes.”

Bi Gan said his ideas are derived from dreams. The problem with Resurrection was how to show them on film. “Visualizing my emotions was so difficult,” he said. “Even angels can’t do it. So what perspective could I use? How about capturing 100 years of film? That became my focus.”

The director’s point was that cinema is an opportunity for viewers to share dreams. “I’m not against media platforms, but when people gather together in movie theaters, it’s something special. It’s not like being at home, watching on a smart phone. That’s like an individual dream. We can experience a dream together in a theater. It’s a communal feeling that can’t be duplicated in any other media.”

Bi’s script (written with Xiaohui Zhai) not only mixed genres, but found inspiration in world cinema. He said it was the first of his films that wasn’t based on personal experiences, but on his perspective of the world. “We started with the early 20th century, deciding which countries to cover, figuring out how to capture angles and sets and color and bring them to contemporary technology. In each subsequent chapter we looked at different genres, different technologies.”

Asked to talk about the New Year’s Eve shot, Bi took pains to point out that he’s not interested in cinematic stunts. “To me, it’s not about how long the shot is,” he said. “It’s not the time, but how it helps get us deeper into the story.”

The director said that the paintings of Mark Rothko were a tremendous influence. He also praised the collaborations with his cinematographer, production designer, and the rest of his crew, saying they helped the shot develop and evolve.

“We did a similar take in Long Day’s Journey Into Night, so shooting a long take is no longer that much of a challenge. The particular details of the New Year’s Eve shot weren’t that difficult to achieve. What was important for me was to provide a clear concept and focus for viewers. That’s where Rothko helped.”

The shot begins from a first-person perspective, following Jackson Yee’s character through increasingly dark and violent alleyways and nightclubs. About halfway through, it switches to a third-person perspective that involves a gangster and femme fatale. “The shot ends as a young couple, two lovers, are running to the port to catch a boat to freedom,” he said. “I wanted to use natural light, but also include the actual sky. That meant we couldn’t control the lighting. After prep and scouting, we had about a week to test the shot.

“I wanted the sun to rise at the end of the take,” he went on, “but for a week all we got was mist and rain. It was only on the very last day of shooting, while the actors were running to the pot, that the light worked out right.”

The director hoped that viewers would watch Resurrection “on the biggest screen imaginable.” He continued, “I put a lot of information into my films. I believe you can only see and comprehend that information on a big screen.”

Bi Gan admitted that he used an iPhone to watch preliminary edits. “But you can’t fully see what I’m trying to convey. You feel it fully on a big screen. With the iPhone I often felt like the film was too long, but watching it on a screen I feel it could be even longer.”

The director worked with Anthony Gonzalez of M83 for the soundtrack, sending him a synopsis before the script was completed. “He sent back lots of music,” Bi said. “We created together, collaborating and adjusting all the way through the production. In fact while we were in the final edit, not all the music had been completed. Anthony kept adjusting the closing. We really needed it done, but he told me the changes would make a big difference. When I finally heard the material, I started shedding tears.”

Bi sees Resurrection as an evolution in his earlier work, especially in its point of view. He also denied that the final scene refers to an end of a cinematic era.

“Cinema will not come to an end,” he argued. “This film isn’t about an ‘era of cinema’ as much as it’s about how audiences reminisce about their memories of film. After all, painting didn’t come to an end. Art does not end. There is still a reason for it.”

Resurrection screened at the 30th Busan International Film Festival and will open in the U.S. on December 12 from Janus Films.