Let’s think about the title to Vivian Qu’s sophomore effort Angels Wear White because the meaning goes far beyond the words themselves. On the surface it’s simply describing religious iconography and the idea that angels wear flowing white linens with halos on heads and harps in hands. But we’ve taken this concept and brought it into real life too. “White” has become synonymous with purity, trust, and expertise. We see a white lab coat on a doctor and automatically provide him/her a reverence built on nothing but an article of clothing. We don’t know them. We merely assume they have our best interests in mind. That white sheen doesn’t mean they’re incorruptible, though. Anyone can be bought or sold despite appearances. Everyone has a price.

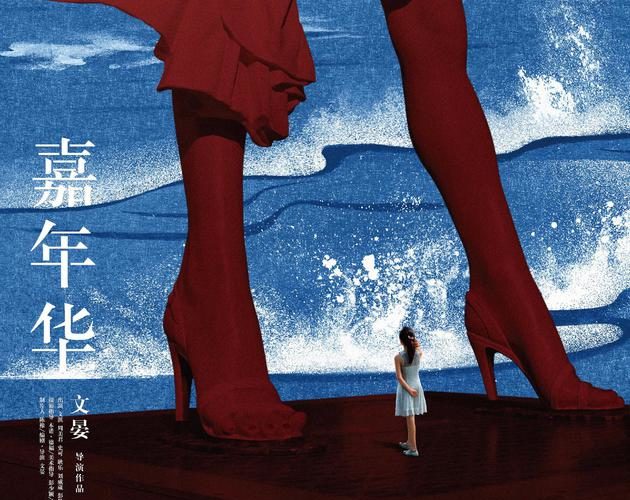

Perhaps the cost is paid with money or maybe silence. For the young women at the center of Qu’s tale of corruption and implicit oppression, every move made is one that can make or break their potential to have a future let alone make it a good one. Just because a bride wears virginal white on her wedding day doesn’t mean she’s a virgin—nor does she have to be despite archaic customs and social expectations. White therefore becomes a shield and in some cases a weapon. Look at the gigantic statue of Marilyn Monroe with skirt blown up that resides in the beachside square of this sleepy little town for an example of the latter. The color of her dress seeks to render her overt sexuality moot.

But we know the truth. We know what that coy giggle and haphazard attempt to cover-up means. Heck, the image is still used in advertisements today courtesy of Willem Dafoe and Snickers. Sex might get dressed up as though it’s being suppressed, but it’s potency only increases. The notion of it being taboo makes it more alluring and memorable. Tourists go to that statue to take photos, it’s juxtaposition against the sandy shores littered by newlyweds either intentionally ignored by or completely lost on everyone. Because underneath those smiles and the nuptials spoken lies a darkness no community can escape in this day and age. Soon that statue will be littered with handbills and trash, the pristine skin of summer strangers disappearing to leave the struggling locals behind.

Some of these mainstays are children like twelve-year old students Wen (Zhou Meijun) and Xin (Jiang Xinyue). Some are drifters escaping a dire past to begin anew with a desire to work despite lacking proper ID like Mia (Qi Wen). Some know the game and use their looks to acquire what they want regardless of the consequences false love gradually lets them forget (Jing Peng’s Lily). And then there are the violent punks (Yuexin Wang’s Jian), the corrupt officials (Cao Yunqing’s Commissioner Liu), and the few admirable citizens who care about justice like Attorney Hao (Ke Shi). Those in between strive to be good, but it’s hard when the promise of better lives is presented in return for ignoring unforgettable horrors. “White” it seems cannot exist without stains.

They’re all thrown together thanks to what seemed a quiet evening. Lily leaves her post as hotel receptionist to go on a date with Jian knowing Mia will cover for her. Mia is taking out the garbage when a car pulls up with a middle-aged man (Liu) and two underage girls in Wen and Xin. So she quickly puts on Lily’s red coat to man the desk and sign them in, skeptically surveying the situation despite having no recourse. If she calls the police, she has no ID. If she tries to help, she’ll be in just as much danger with Liu considering she’s barely a teenager herself. All Mia can do is film the man forcing his way into the girls’ room on her phone and wait.

From there Qu’s film spirals out of control as no one wants to talk. It’s a matter of self-preservation all around with Wen and Xin trying to avoid a beating from their mothers while Mia and Lily try to keep their jobs. No one wants trouble because the implication of what happened is just as damaging as an accusation. This is a culture where plastic surgeons focus on hymen reconstruction to fool prospective suitors. It’s a community that relies on greasing palms and having connections wherein turning the other cheek could be lucrative for witnesses and victims alike. Only Hao and Lieutenant Wang (Mengnan Li) seem to want the truth, their sole angle directing them to justice while the rest weigh their myriad options. It’s a devastating reality.

We watch each lose his/her innocence whether Wen’s mother (Weiwei Liu) avoiding her own complicity courtesy of an abusive relationship mired by stints of being absent from ensuring her daughter’s safety or Mia’s opportunity to leverage the evidence in her possession as a means towards illegally obtaining an ID. Xin’s parents wonder if prison is the justice they want when a payoff might be on the table and the “deadbeat” of the group—Wen’s father Meng Tao (Le Geng)—somehow becomes the voice of reason thanks to a turn of the leaf that has him rejecting the selfish life he once led. And all the while these two sweet little girls who just want to play and be kids don’t know if they’re the ones who did wrong.

What is anyone to do when the “right” choice seems to carry the burden of more harm? Qu writes her characters to confront their personal ambitions and needs over others in a way nobody ever likes to think about. Rather than see the nightmare for what it is and the victims for whom they are, everyone angles for an outcome that benefits them: their reputation, social standing, or financial straits. The survivors of sexual abuse become pawns; leverage in a game played far too often in nations with more transparency than even the Chinese environment onscreen. The system meant to protect them breaks down until silence seems more advantageous than truth. And like I said above, what would truth provide? Can Hao and Wang be trusted?

Angels Wear White becomes a bottomless pit of despair consuming complex characters with nowhere to go. There’s a glimmer of hope at the very end, but it can’t help from feeling bittersweet considering the long list of people who’ve been virtually run over by a freight train of hearsay, double-talk, and empty promises. Everyone who offers a helping hand must be questioned because the prospect of them asking for more when someone agrees always seems more likely than actual assistance. The futility is overwhelming, the ease towards protecting the predator over prey disgusting in its absolute authenticity. And when you begin to understand that you can barely trust your own actions, how can you bring yourself to trust anyone else? More and more our world shows we can’t.

Angels Wear White screened at the BFI London Film Festival and opens May 4.