What is it about avant-garde films? They feel rebellious. New. Dangerous. The form is literally being poked, prodded, criticized, and challenged. Above all else, they are exciting. And few filmmakers in the field were more exciting than Roger Jacoby. A still-underrated pioneer of experimental filmmaking, Jacoby came up in New York’s 1960s art scene alongside visionaries like Andy Warhol and Ondine before relocating to Pittsburgh in 1972 and making his indelible films. He sadly died in 1985 at the age of forty from complications with AIDS. The exhibition “Roger Jacoby: Pittsburgh Stories” at Wood Street Galleries, now underway through January 5, 2025, features the world premiere of 4K restorations of three of Jacoby’s short films: Dream Sphinx Opera (1974), L’Amico Fried’s Glamorous Friends (1976), and How to Be a Homosexual Part I (1980). Also showcased is his Bolex camera, as well as an instructional video in which he demonstrates how he went about processing his film from 1974. It is a simple, lovely showcase.

The Film Stage was fortunate enough to visit the exhibition and have an extended conversation over email with curator Anastasia James, Director of Galleries & Public Art for the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust. She offers essential context to Jacoby’s importance as both a queer artist and a Pittsburgh artist: “Jacoby’s relocation to Pittsburgh marked a profound shift in his creative journey. Here, amidst the city’s burgeoning experimental film community, he found a home at Pittsburgh Filmmakers and forged a significant bond with Sally Dixon, the visionary curator at the Carnegie Museum. It was in the intimacy of his own bathroom, embracing a DIY ethos, that Jacoby’s films took shape—each frame a tactile meditation on the materiality of film. In works like Dream Sphinx Opera and L’Amico Fried’s Glamorous Friends, his manipulation of emulsion imperfections became a language of abstraction, where texture and time bled into evocative, haunting imagery. In How to Be a Homosexual Part I, Jacoby turned the camera on himself and his community, capturing intimate portraits of queer lives—stories often silenced or erased by mainstream cinema.”

The films are newly restored, through the preservation efforts of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, and presented immaculately in a brutalist screening room, playing all three films on a loop. It’s a beautiful, spare presentation that draws all focus to the work itself.

These are wonderful oddities, each one entirely unique from the next. Dream Sphinx Opera, starring Sally Dixon and Ondine (Chelsea Girls) is perhaps his best-known film, an eight-minute piece complimented by the beautiful voice of Maria Callas (singing “Una voce poco fa” from Rossini’s opera The Barber of Seville). Jacoby’s signature hand-processing is a lovely compliment to Dixon and Ondine’s dancing and flirting in period clothing within Phipps Conservatory. Everything is playfully obstructed by emulsion.

L’Amico Fried’s Glamorous Friends––also featuring Sally Dixon and Ondine––takes it a step further. This film is a wonderful showcase of the extreme levels of processing Jacoby would inject into his work. And while there are some essential Pittsburgh locations on display (most especially the Carnegie Museum of Natural History), the celluloid itself is the star here. Various forms of dance offer a constantly engaging frame. Figures bouncing behind fascinating objects.

Finally, How to Be a Homosexual Part I is more ambitious. A documentary that features a quite-arresting opening interview with a teenage gay activist describing his coming to terms with his “gay feelings” and dealing with “gay self-hatred” within the queer community. “Fighting the enemies instead of fighting ourselves” is a line uttered early on that lingers through the picture. The camera never sits still, bouncing around the room, from the subjects’ faces to a framed photograph on the wall and back. What follows is a rather touching sequence in which Jacoby has a conversation with a young man who is deaf.

James expands on this scene, noting, “One aspect of Roger Jacoby that many people might not immediately know is his deep connection to the deaf community, which became a central part of his life later in his career. After meeting a number of deaf gay men in Pittsburgh’s bathhouses, Jacoby was moved to learn American Sign Language (ASL) and became a trained sign language interpreter for the deaf. This shift in his life reflected his broader commitment to inclusivity and his desire to connect more deeply with marginalized communities. His involvement with the deaf community added another layer to his identity as both a filmmaker and an advocate for those on the fringes of mainstream society, expanding his work beyond the camera and into the realm of personal connection and advocacy.”

Roger Jacoby, How to Be A Homosexual Part I, 1980. Courtesy Canyon Cinema Foundation and the Estate of Roger Jacoby.

As referenced, the city of Pittsburgh is crucial to the story of Roger Jacoby. Its experimental film community thrived in the 1970s, as Pittsburgh Filmmakers emerged as a center for artists in the region. “Roger Jacoby’s evolving relationship with other experimental filmmakers in the region was marked by his active participation in and contribution to the vibrant underground and avant-garde film scene, particularly in the 1970s surrounding Pittsburgh Filmmakers and the communities cultivated by Sally Dixon. His work was influenced by and, in turn, influenced a community of filmmakers who were pushing boundaries and exploring new cinematic forms, often centered around personal expression, political engagement, and the rejection of mainstream film norms,” explains James. “Jacoby’s relationships with other artists in the region was also shaped by shared creative struggles and the influence of the political climate and his relationship in the late 1970s with the activist and filmmaker Jim Hubbard, particularly around issues of LGBTQ+ rights and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. His films were not only creative statements but also acts of defiance and documentation, positioning him as both an artistic peer and a voice for the gay and activist communities in the avant-garde film world.”

So, once again, what is it about avant-garde films? James puts it perfectly: “There is something inherently alive in experimental film—something that escapes the logic of order and invites us into a liminal realm. When I watch these works, it’s as if the film itself is an act of liberation, pulling us away from the constraints of narrative, allowing us to witness not just a story but an experience, a feeling––a memory of a beautiful and complicated life lived. I agree with you that they can feel dangerous in that they hold the power to reveal something profound about the world—and about ourselves often in unexpected or unanticipated ways – a feeling that can linger with you for days or even years, quietly reverberating long after the screen goes dark.”

A winter trip to Wood Street Galleries offers both escape and discovery, and perhaps something you’ve never quite seen before. All thanks to Roger Jacoby.

Roger Jacoby: Pittsburgh Stories is on exhibit through January 5 at Wood Street Galleries.

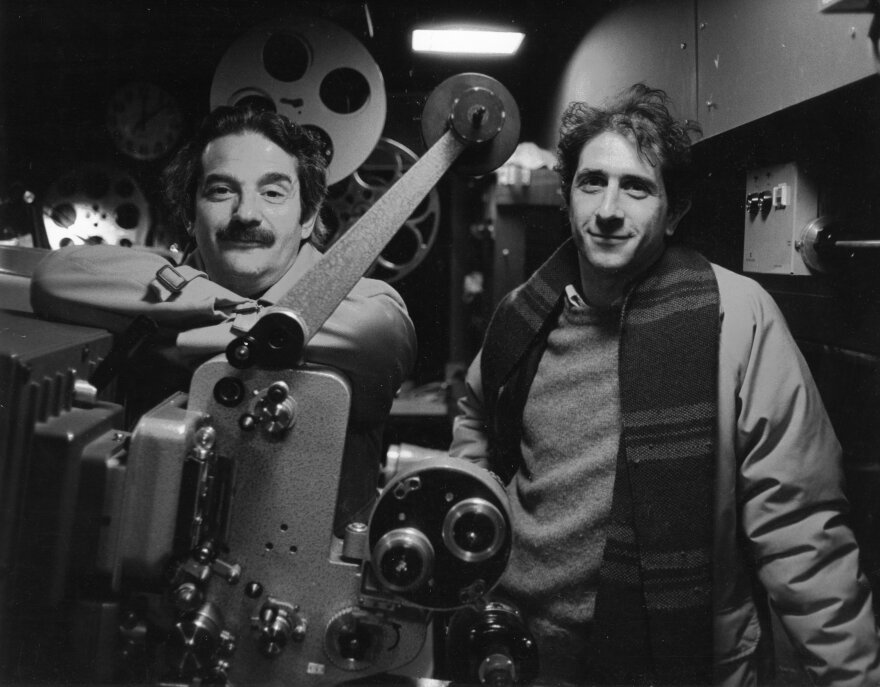

Ondine and Roger Jacoby in Pittsburgh, courtesy of the Estate of Roger Jacoby