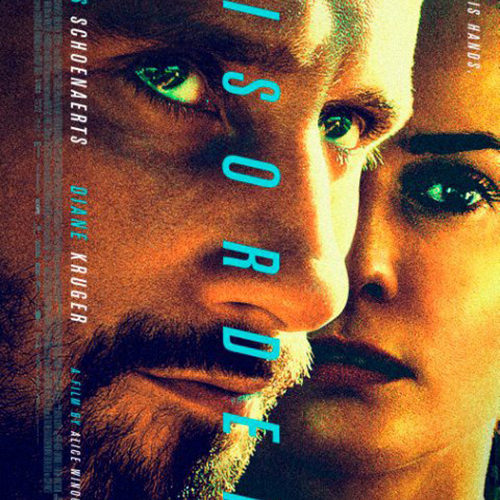

Disorder tackles the home-invasion thriller on an unusual front, emphasizing paranoia and uncertainty over any nightmare of intruders coming to get you; the home isn’t even invaded until rather late into the plot. Until then, it’s a character study of Vincent (Matthias Schoenaerts), a soldier who, despite being eager to get back to the front, knows he won’t be able to because of his hearing loss and PTSD. In need of work, he joins in on a buddy’s personal security company, and ends up assigned to be a bodyguard for Jessie (Diane Kruger) and her young son for 48 hours. Soon, though, it emerges that Jessie’s husband’s shady business dealings have put her in danger, and Vincent has to hold it together in order to protect her and her son.

Home-invasion films generally carry class-based anxiety, and Disorder takes that to the extreme, set as it is within a spacious manor compound. Rather than reflecting a fear of the poor, however, the bad guys are a spectre of the fallout from high-level deal-making. Jessie’s husband is an arms broker, and news stories about the Islamic State and political maneuvers continually crop up in the back- or foreground throughout. Vincent’s situation is one born of globalization, being a Frenchman protecting the German-born wife of a Lebanese businessman from vaguely Middle Eastern criminals. He may not be in the army anymore, but he’s still stuck with cleaning up political meddling in Central Asia.

That subtext is interesting, but only carries Disorder so far. A good deal of it stretches on interminably with Vincent looking sad, weary, on edge, or some combination of the three. Writer-director Alice Winocour does a fine job establishing the geography of Maryland, Jessie’s sprawling estate, and inducing anxiety by framing distant spaces against Vincent’s gaze as it roves for danger. But after a certain amount of inaction and anticlimax, a slow burn is just a fizzle. At 100 minutes, it uses up its suspense tricks early. It doesn’t help that, when violence finally breaks out, the action is shot and edited utterly without sense. It goes beyond the cliche idea of “shaky cam” into what honestly feels like completely random shots machine-gunned together.

As always, Schoenaerts carries stoic masculinity like a familiar haversack. Most aspects of the film’s depiction of PTSD are clichéd (bolting awake at night, flash-quick memories triggered by innocent incidents), but he’s nevertheless able to make a steely, haunted brooding turn magnetic. Yet he and Kruger can’t sell the low-key attraction that develops between their characters, which turns a lot of the stakes — and the story’s resolution — into absolute shrugs. This is what Disorder ultimately adds up to.

Disorder played at AFI Fest and will be released by Sundance Selects on August 12.