Ridley Scott is finally returning to science fiction with the Alien prequel-thing Prometheus. That alone is almost enough to erase the vinegar-spag after-taste of A Good Year from our collective memories. That Scott will be returning to the world of his iconic Blade Runner is even better news. We’ve examined the possibilities in great depth already, but what about the Philip K. Dick book which inspired it? That’s where I come in.

Let’s discuss the great sci-fi writer with that hilarious last name for a minute. Philip Kindred Dick and his twin sister Jane were born six weeks premature in Chicago. Dick’s sister died six weeks later. The loss of his twin affected him profoundly – indeed, the motif of a “phantom twin” shows up often in his fiction. His family moved to the San Francisco Bay Area and Dick attended Berkeley High School with fellow future sci-fi author Ursula K. Le Guin.

Despite dreams of achieving mainstream literary success, Dick’s only saleable output was a steady stream of science-fiction short stories. His life was plagued by financial trouble – a harsh irony given the many posthumous big-budget Hollywood adaptations of his work: Total Recall, Paycheck, Minority Report. His non-hard-sci-fi book, Man in the High Castle, won a Hugo Award in 1963 and 1975’s Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (about a celebrity who wakes up in an alternate universe where no one has any memory of him – and which could be an amazing adaptation along the lines of Richard Linklater‘s superlative A Scanner Darkly) won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for best novel.

Toward the end of his life, Dick would nonchalantly drift through five marriages, a host of girlfriends, stints in rehab, drug overdoses and suicide attempts. In February of 1974, Dick received a dose of sodium pentothal during the extraction of an impacted wisdom tooth. The month that followed consisted of prolonged visions and hallucinations. At one point Dick believed he was leading “a double life” as Philip K. Dick, but also as “Thomas,” a Christian who was apparently being persecuted by Romans in the 1st century A.D. His belief that the visions were being transmitted to him via a “transcendentally rational mind” would form the basis of several of his later books, including Radio Free Albemuth (the closest thing to a straight autobiography of the experience), The Divine Invasion, The Transmigration of Timothy Archer and VALIS (an acronym which means Vast Active Living Intelligence System).

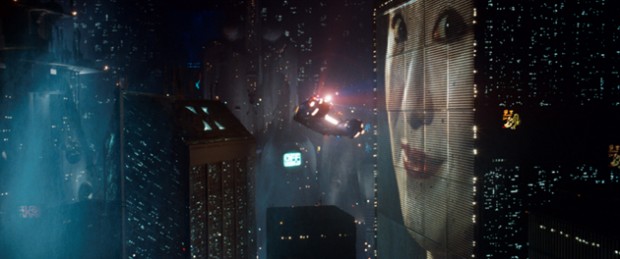

Why has Dick’s vision of the future of human civilization become so pop-culturally significant? He foresaw a society so completely wired into each other’s lives that we’d be forced to inform on each other to keep The System at bay (A Scanner Darkly), while distracted and pumped full of chemicals. We’d even reach a breaking point and grow so bored that we’d turn to drugs which would actually make us perceive a completely different dimension (Flow My Tears). Philip K. Dick was George Orwell and Isaac Asimov joined at the genetic level, with a hefty dose of acid thrown into the mix. The steampunk-ian visions of Blade Runner‘s dystopian future are as depressing as they are wondrous, so it’s easy to forget that most of Dick’s novels end with the same message: don’t succumb to artificial interpretations of the world around you, don’t let anyone subvert your personality and let’s just be nicer to each other, yeah?

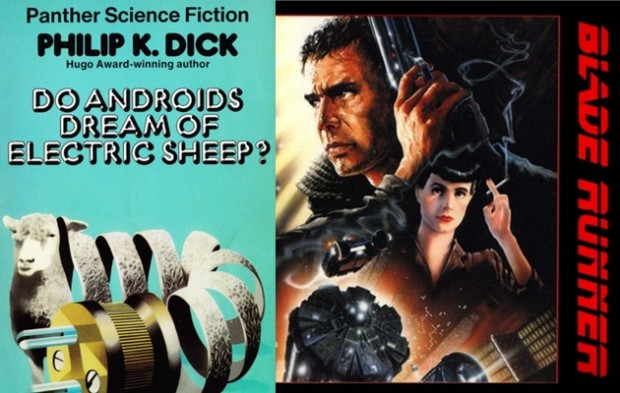

This philosophy can be found in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the book Blade Runner is based on. What you won’t find anywhere in that book is any reference to “replicants,” the “Tyrell Corporation” or the term “blade runner” itself. Not terribly surprising, since neither director Ridley Scott nor screenwriter Hampton Fancher read the book prior to filming, or so the story goes.

According to Paul M. Sammon’s Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner, Fancher read a treatment by William S. Burroughs for a film adaptation of a 1974 novel by Alan E. Nourse called The Bladerunner. Scott liked the title and hired David Webb Peoples (Unforgiven) to rewrite the script.

All of which is doubly strange given Philip K. Dick’s positive impression of the portions of the film he would see, since he did not live to see the film’s release. In Dick’s words:

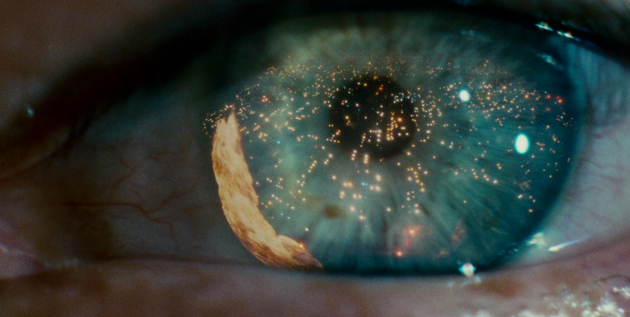

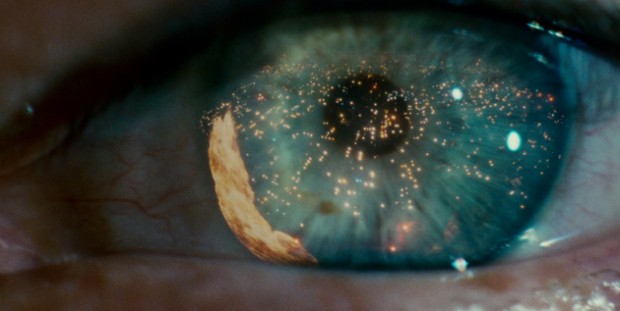

“I saw a segment of Douglas Trumbull‘s special effects for Blade Runner on the KNBC-TV news. I recognized it immediately. It was my own interior world. They caught it perfectly.” He also approved of the film’s script, saying, “After I finished reading the screenplay, I got the novel out and looked through it. The two reinforce each other, so that someone who started with the novel would enjoy the movie and someone who started with the movie would enjoy the novel.”

Fair enough. Indeed, Fancher and Peoples’s adaptation adds certain key elements that would appear again and again in Dick’s other work – perhaps most prominently in A Scanner Darkly – and would on some level or another inform every epic sci-fi film since: vaguely sinister global corporations, the distinct film noir tone, the uncertain shifting of identities. (Re-watch Inception, The Adjustment Bureau [also based on a Dick story], Luc Besson‘s The Fifth Element [memorably described by Peter Travers as “Blade Runner on giggle gas,”] Danny Boyle‘s underrated Sunshine, and Steven Soderbergh‘s remake of Tarkovsky‘s Solaris – all of these movies have a touch of Philip K. Dick, whether they know it or not. And, of course, there’s Richard Linklater’s amazing rotoscope-animated A Scanner Darkly, a terrific film in its own right which to date is still the most faithful Dick adaptation out there. I’ll deal with that one in a later column.)

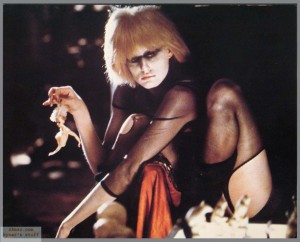

The book’s major theme is one of disconnection. In the film, Daryl Hannah‘s character, the “standard pleasure model” replicant Pris, is a waif-ish, seemingly simple-minded (and very limber) death machine when cornered. Her counterpart in the novel is a normal-seeming android (or “andi,” as they’re called in the book) who moves into the same building as a minor character, a taxi driver. The two form an offbeat friendship as bounty hunter Rick Deckard hunts down the other androids who have illegally settled on Earth – in the meantime, Deckard is annoyed that his wife has begun to program her “mood organ” to emit unsound emotions, such as depression. A subplot follows one of the society’s major religions, Mercerism, which is based on the suffering of a man named Wilbur Mercer, who takes an endless walk up a mountain while rocks are hurled at him – the pain of this experience is shared by followers via Empathy Boxes, virtual reality machines linking the users.

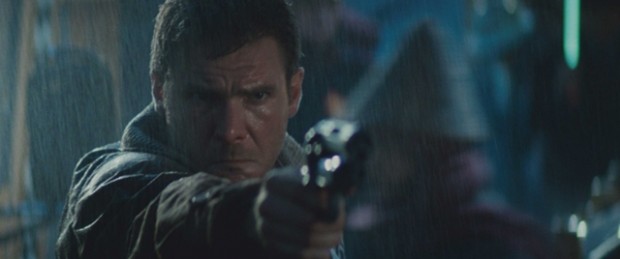

Unsurprisingly, none of this made it into the final film. Blade Runner‘s Deckard is single, freshly retired from killing replicants until called back in to chase down Roy Batty (the brilliant Rutger Hauer) and the replicants who followed him. One major through-line of the book was kept: Deckard’s romantic relationship with Rachael (Sean Young), a next-generation replicant so realistic that it takes a marathon Voigt-Kampff test to determine whether or not she’s real. In the book, Rachael tries to turn Deckard away from bounty hunting, but he leaves her in the end. Interestingly enough, the novel’s Rachael and the novel’s Pris are identical to each other – two versions of the same woman, serving different functions.

Unsurprisingly, none of this made it into the final film. Blade Runner‘s Deckard is single, freshly retired from killing replicants until called back in to chase down Roy Batty (the brilliant Rutger Hauer) and the replicants who followed him. One major through-line of the book was kept: Deckard’s romantic relationship with Rachael (Sean Young), a next-generation replicant so realistic that it takes a marathon Voigt-Kampff test to determine whether or not she’s real. In the book, Rachael tries to turn Deckard away from bounty hunting, but he leaves her in the end. Interestingly enough, the novel’s Rachael and the novel’s Pris are identical to each other – two versions of the same woman, serving different functions.

There are several versions of the film’s ending, depending on which cut you see. Blade Runner: The Final Cut is the most recent, and the one with the most compelling argument that Deckard himself is a replicant. After all, as anyone who’s seen the film multiple times will tell you, at length: Deckard’s mission was to track down “six replicants, three male and three female.” In the course of the film, Deckard “retires” two male replicants and two female – leaving us to wonder who the third male and third female was. One of them, we’re told, was killed before the story began… but which one? Visual clues (the vision of a unicorn which seems like an outtake from Ridley Scott’s Legend) and Scott’s inference lead to the conclusion that Deckard is a replicant – one of the six that escaped? That doesn’t make much sense, but it isn’t really supposed to.

The film’s best and most fascinating character isn’t Deckard, anyway. Hauer’s Roy Batty is an intense, charismatic “combat model,” who comes to Earth in search of that most human urge, to find the truth about his existence. His confrontation with his maker, the creepy, sinister Tyrell, is a condensed version of any person’s epic frustration and disappointment: Nexus 6 models like Roy were designed to have a four-year life span, a built-in self-destruct to occur before they develop their own native emotions. Tyrell tells him that “The light that burns twice as bright burns for half as long – and you have burned so very, very brightly, Roy.” Tyrell never admonishes Roy for the havoc he’s caused or the lives he’s taken. Indeed, Tyrell seems proud of his prodigal son. This reinforces Roger Ebert‘s notion that Tyrell might have had a deeper plan for his near-human replicants: were they meant to eventually replace humans? This intriguing idea could prove an interesting plot-line for a sequel.

The film’s climax is the extended showdown between Deckard and Roy Batty, a tense cat-and-mouse game played out against the decaying tenement apartment building of J.F. Sebastian (William Sanderson), a Tyrell employee who helps create the replicants. Sebastian’s home is full of his own home-made replicants, an eerie hall of puppets. Pris dies at Deckard’s hands, and Roy mourns her, howling like a wolf. Watch the light during this scene: like in the rest of the movie, the light is constantly shifting and moving, filtered through smoke or steam, refracted through water, the piercing beams of floodlights waving around outside the windows.

The effect reinforces the noir-ish aspects of the film, and the deep shadows provoke our doubts about the characters’ identities. Roy pursues Deckard to the roof of the building, staving off his imminent, built-in expiration by jamming a nail through his own hand. It’s an evocative Christ-symbol – he even cradles a dove in one shot, right before his final speech to Deckard. There is a general rule that the protagonist of a story is the one who changes the most by the ending. In this case, it’s Roy Batty. As he tells Deckard, “I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time… like tears in rain…”

In the unnecessary narration of the theatrical version, Harrison Ford intones that maybe Roy loved life in his dying moments as he never had before, and that’s why he let Deckard live. Or maybe he knows Deckard is a replicant himself, and wants him to appreciate what he has. Is Roy our Savior, then? It’s a much more subtle exploration of the Christ allegory than the novel’s heavy-handed subplot involving the society’s Mercerism religion. Philip K. Dick was more interested in our belief systems and perception of what’s human and what’s not. Ridley Scott adds a streak of masochist pain to the mix, most likely his way of dealing with the recent death of his older brother from skin cancer. Many critics of the film’s initial release called it “science-fiction pornography,” (as if that were a bad thing.)

The film was not a huge success when first released – it opened opposite E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, which of course dominated the box office that summer. That doesn’t matter anymore: Blade Runner continues to haunt our dreams. We may not be living in it’s dirty, smoky future just yet (although it’s vision of a fire-belching, industrial-sprawl of Los Angeles really isn’t that far off), and we don’t have those impractical and wildly dangerous flying cars… we’re surrounded by shifting, winking billboards, though. We may not go off-world within my lifetime, but the essence of the book and film remain intact and relevant: life is precious. Try not to waste it.

Have you read Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep? Are you looking forward to another Blade Runner movie?