Comprising international premieres, short programs, and some of the country’s finest-ever films in new restorations, 2024’s Japan Cuts––running July 10-21 at New York’s Japan Society––is upon us. As one of North America’s sole festivals devoted to new voices in Japanese cinema, it’s likely your only opportunity to see many titles in a theatrical space. Though one can feel a bit dizzy looking through everything, we’re glad to distill it––from masters (Takeshi Kitano, Shinya Tsukamoto, and Gakuryu Ishii) to nascent talents and, along the way, a few absolute classics given much-deserved restorations.

All the Long Nights (Shô Miyake)

Shô Miyake’s All the Long Nights is a film about small things: decency, kindness, why people help each other out, how those acts can inspire others. The first character we meet is Misa (Mone Kamishiraishi), a sensitive type who suffers from premenstrual syndrome. In the opening scene, this causes Misa to lose her cool at work, and while the situation is smoothed over, she quits out of shame. Leaving the city, she lands a gig in a suburban company, assembling astronomical sets, and meets Takatoshi (Hokuto Matsumura), a young, panic attack-prone man who recently left a job under similar circumstances. After an initial misunderstanding, their orbits align into something that looks like love but never skews romantic. – Rory O. (full review)

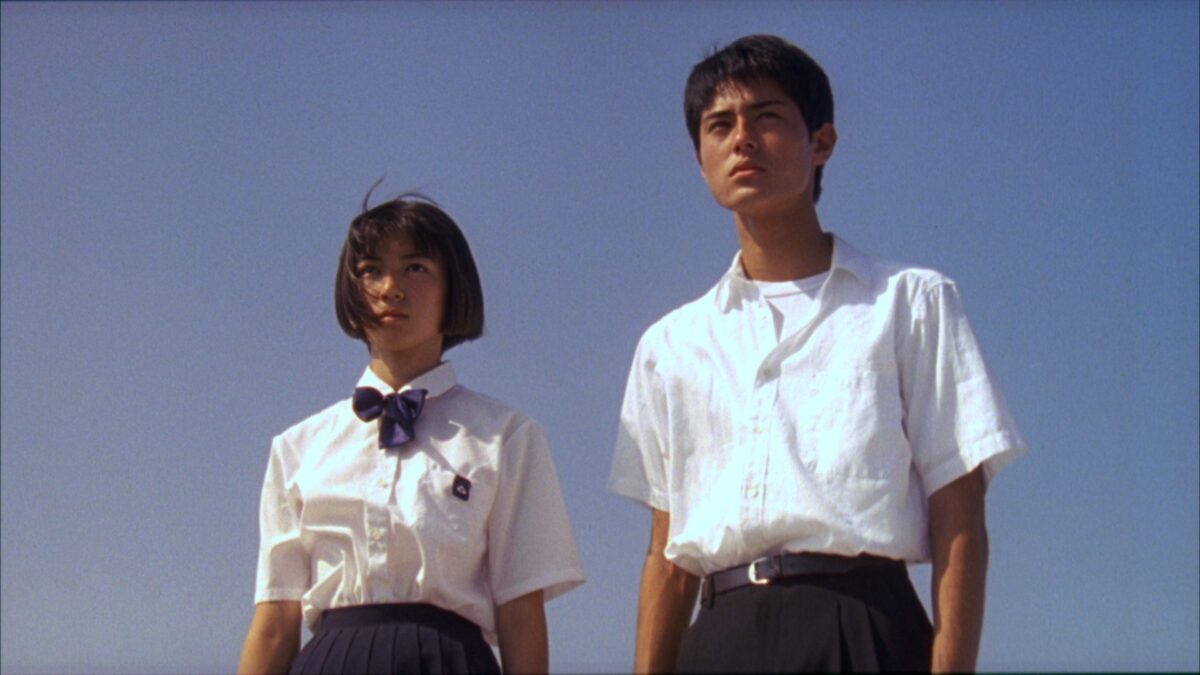

August in Water (Gakuryū Ishii)

Gakuryū Ishii’s philosophizing enters a realm of the ethereal here, with its soft, sun-dipped aesthetic and tranquil voiceover juxtaposing a quiet but teetering societal collapse in a small Japanese town. Starting initially as a college-sports drama and then morphing into a sci-fi-adjacent adventure film, August in the Water is like an extended Japanese episode of The Adventures of Pete & Pete, taking a quintessential coming-of-age drama and expanding on it to a cosmic level that considers the boundaries of its urban environment to be not quite so isolated. Its hypnotic score and dream-like camerawork teleport the movie’s rather plain landscape into a metaphysical realm channeling our world, what’s inside us, and what exists beyond our knowledge. – Soham G.

The Box Man (Gakuryū Ishii)

More convoluted than it is complex, Gakuryū Ishii’s The Box Man, adapted from a novel by Kōbō Abe, has the ingredients of worthy inspirations––from Hiroshi Teshigahara, whose Woman in the Dunes was also written by Abe, to Shinya Tsukamoto, a cyberpunk brethren––but is unable to concoct them into much of note. This is an absurdist psychological drama that unravels as it tries to put itself together. Built on Ishii’s patented multi-threaded storylines that weave through various interconnected themes of self-realization, out-of-body experience, and navigating a dense urban landscape, this movie––if not quite successful in its aims––fascinates as a surreal narrative experiment. – Soham G.

Kubi (Takeshi Kitano)

For all their grisly mayhem, the earliest films by Takeshi Kitano all demonstrated a keen grasp of negation. Violence was an omnipresent fixture of his first crime capers––from Violent Cop (1989) to Fireworks (1997)––but it unfolded in hiccups. The director enjoyed trading in tantalizing elisions, and his most gruesome scenes would often leave the action offscreen, offering a set-up and aftermath while cutting the most dramatic moments––an approach that would become more frequent after A Scene at the Sea (1991), the first feature he’d edit himself. It was as if Kitano had realized the most visceral shots were those left on the cutting room floor and proceeded to fashion those early projects on an iceberg principle: prodding one to imagine the bloodletting without ever displaying it in full. It was a style predicated on absence; it made the violence all the more vivid, the films all the more original. – Leonardo G. (full review)

Mermaid Legend (Toshiharu Ikeda)

Few movies have ever convinced me of a director’s genius like Mermaid Legend, perhaps because few climaxes have ever made my jaw drop with such force. Word of this film’s accumulated through years of back-channel distribution, anybody who sees a worn-looking copy rarely prepared for the slow-burn-until-it’s-not revenge thriller. Though there are many works that resemble it from the outside, this is the perfect vision, and the 40th-anniversary restoration suggests a new entry in the canon. – Nick N.

Moving (Shinji Somai)

In a pivotal sequence of familial infighting, the young Renko yells out from a bathroom she has locked herself inside, “Why did you have me?” The framing of scene, blocking its characters in a crowded hallway and shutting out Renko, aims to create a sense of crowdedness and disrepair. Framing is consistently, consciously at the forefront of Shinji Somai’s Moving, where characters are cut across, divided, and askew amid the Japanese architecture of Renko’s home. This coming-of-age story about a young girl dealing with her parents’ divorce uses the doors, walls, stairs, and corners of what was once a wholesome family home to exacerbate Renko’s feeling of being split in half among her parents and outright neglected in their decision-making. A carefully compassionate and bittersweet movie. – Soham G.

Rei (Toshihiko Tanaka)

Rei begins with a definition of the term: a kanji character that doesn’t really signify anything, but could in theory signify everything––a placeholder. Toshihiko Tanaka’s Rotterdam-winning debut tells the sprawling story of Matsushita Hikari, a woman who strikes platonic friendships with a theater actor and deaf photographer, forming a bond with both. Disability-centered relationships are a central conflict in several of the storylines that tend to seep into melodramatic and patronizing territory, but it creates a densely layered portrait of the ways Japanese society is built on fear of fracture––between generations, between those abled and disabled, even between those of “respectable” and “different” occupations. – Soham G.

Shadow of Fire (Shinya Tsukamoto)

Shinya Tsukamoto’s Shadow of Fire begins as a troubling but measured film, but about a half-hour in something happens that shatters its quietude. Suddenly, a man who to this point has been impotent and deferential throws a small boy out a window and begins beating a woman. From the director best-known for Tetsuo: The Iron Man, and whose other films are often similarly stylish and sexually violent, that might not sound like much, but it is precisely the restraint of Shadow of Fire that makes the violence one of the more harrowing moments in Tsukamoto’s growing oeuvre. – Forrest C. (full review)

Japan Cuts 2024 runs from July 10-21 at Japan Society. See the trailer below.