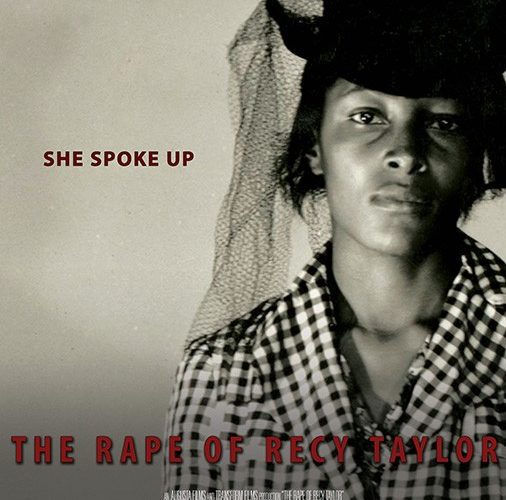

You may not know the name Recy Taylor, but you’ve definitely heard her story. It’s one of rape, lies, and cover-ups. It’s one of irreparable physical and psychological damage that still affects her family more than seventy years later. And it’s also one about a woman her refused to be silenced, who came home the night of September 3, 1944 to tell her father and husband everything about the six men that brutalized her. She was twenty-four at the time, a mother one of and partial caretaker of her siblings considering she helped raise them once their mother passed away. Threatened at gunpoint, her house set on fire, and the victim of constant abuse during Jim Crow in Abbeville, Alabama, Recy never stopped her quest for justice.

So why haven’t we heard about her? Why haven’t we heard about one of the few black women in the 1940s that called out her assailants by name? The reason is simple: indifference. It’s the same indifference that lets countless Americans today victim blame with impunity. It’s the same indifference that allows a man like Roy Moore to continue his run for the Senate despite being accused of pedophilia. It’s the same indifference that forces us to watch a chauvinistic predator who admitted the way he treats women without a shred of respect on tape claim the title of President of the United States. This country still facilitates the erasure of women. It still treats them like they’re invisible. And that’s why Recy’s story is so important.

Directed by Nancy Buirski, The Rape of Recy Taylor takes a deep dive into that horrible night and its aftermath through the recollections of her younger sister (Alma Daniels) and brother (Robert Corbitt). They tell the tale with full candor, setting the stage as Crystal Feimster (Assistant Professor of African American Studies and American Studies at Yale) and Danielle L. McGuire (author of At the Dark End of the Street) provide crucial context to Recy’s role in the civil rights movements. It’s a harrowingly vivid picture that’s painted, one augmented by the imagery of “race films” from the early 1900s depicting the torture and violence experienced. And like so many similar accounts, we learn how a Southern law enforcement system built to protect its own does exactly that.

What makes this specific account necessary to single out is the way in which it ballooned well outside the borders of Alabama to inspire the entire nation. Rosa Parks — a decade before she refused to give up that bus seat — was sent as an NAACP investigator to discover exactly what happened and was thrown out twice for her trouble. She would take Recy to Montgomery and rally a movement around the goal of attaining justice for what those six men did. It became a cornerstone until something newer came along and yet it was never rendered less important because it gave a voice to the countless black women still treated like property. It gave them an example of courage to single-handedly lead boycotts and enact real change.

The film is therefore a resonate, timely, and essential one simply because of its role in educating audiences about Recy Taylor and the unheralded women who did so much during the civil rights movement despite constantly being relegated to the shadows while orators like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X stole the spotlight. And that story does ultimately transcend what proves to be a documentary hampered by an awkward visual aesthetic. Buirski too often projects images upon images with a translucency that only works to make both indecipherable. Rather than fade one out as the other fades in to replace it, she’ll have a widescreen shot of trees or buildings infiltrated by a full frame box of old film that disappears before it ever reaches full opacity.

So we have to wonder if either image truly demands attention or if they’re merely thrown onscreen to give us something to look at while the interviews are heard above them. It’s tough because leaving the project a series of talking heads would inherently make it less interesting and yet the familiarity of doing so might also allow it to be more coherent. I did like the notion of bringing in these rare films made by black artists for black audiences to provide complexity to black characters Hollywood wouldn’t, but they’re rarely used in a way that lets us watch them. Too often they transform into textures against disparate present-day locales. To say it’s a ghosted image of the past projected atop today, however, would be a stretch.

I would also question the decision to hold Recy back until the end. We hear her voice early on so we know that either Buirski talked to her or someone else interested in the story did. We therefore assume that footage does exist of her telling her side to complement the emotional accounts of her siblings. It’s these visible depictions of the incident’s impact so long after the fact that really hit home whether Alma’s rage, Robert’s love, or Feimster’s obvious passion and respect for what Recy did despite the trauma and pressure surrounding her. Seeing that same passion on the subject’s face earlier could have brought added impact — at least more than the reveal being postponed to contrast what happened to her rapists provides.

Whatever issues I have with the final construction don’t alter the reality that Recy Taylor’s story must be told and seen. This is especially true today as the most vocal and high-profile proponents of #MeToo and the quest to give women voices are white and sadly prone to causing different issues by the way they implicitly remove women of color from the conversation. As the opening lines Buirski places onscreen explain, the number of black women who have been raped is too high to even begin to quantify. How they were treated as subhuman post-slavery and the stigma still attributed to them (don’t forget Harvey Weinstein finally “defended” himself against accusations only when Lupita Nyong’o told her story) demands their own pillar of strength. Recy Taylor is she.

The Rape of Recy Taylor opens in Los Angeles on Friday, December 8th and New York City on Friday, December 15th.