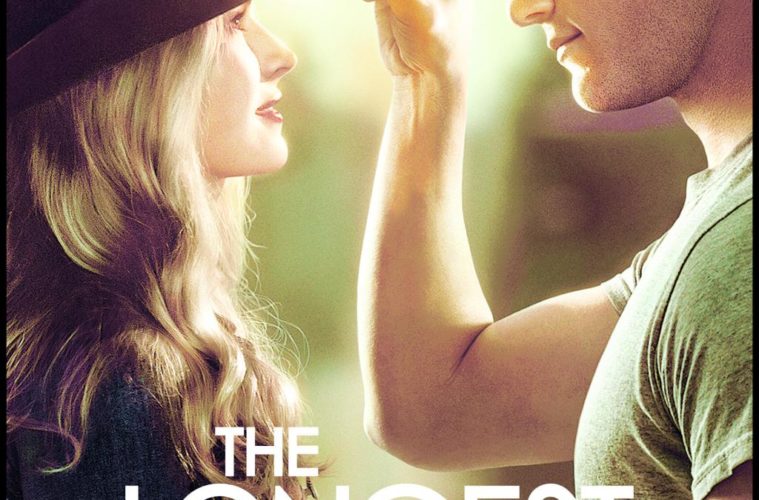

It’s easy to feel like a bully when approaching a movie based off a Nicholas Sparks book. The bestselling author has long since identified his particular saccharine-filled niche in the universe, and like most mainstream entertainers, has been exploiting it for all its worth ever since. After fans and critics alike have sat through The Notebook, Last Song, Message in a Bottle, Dear John and Safe Haven, it can be reasonably asked what a film like The Longest Ride could possibly offer us, outside more of the same. The latter is exactly what we get, and if you aren’t hankering for another slice of that pie, it’s easy to turn on the doe-eyed, mewling dollop of cuteness that is the latest Sparks puppy. Not a single solitary thing in Ride itself is going to divert you from your task, either.

An optimistic person might call each of Sparks’ romantic adventures the author’s variations on recurring themes; star-crossed love, fidelity beyond circumstances, fate and destiny, the passionate allure of North Carolina and old-fashioned, ‘down home’ values. To risk sounding slightly more cynical, I’ve always been of the mind that every one of the Sparks films I’ve seen isn’t merely an excursion into the same headspace, or a jaunt through a carefully coiffed author’s universe, but essentially the exact same tale, switched out with a few new parts, here or there. Whereas popular authors like Tom Clancy and Stephen King have tapped into great success by creating a very specific and recognized style and place for their body of work, the land of Sparks seems to take this branding another step forward altogether, revealing itself as a sleepy hamlet populated by only one, whose been repeatedly cloned to give the illusion of multitudes.

What I’m getting at here is not that The Longest Ride is critic proof, but rather decrying it on the basis of an inventory of its narrative elements—all long-held Sparks mainstays—isn’t particularly useful. In an honest assessment of the films, I can attest that The Notebook, A Walk to Remember, and—to an extent—Dear John, are effective adaptations of the Sparks experience, overcoming some of the traps of the material with spirited performances or energetic and sincere filmmaking. One of the recent and most absurd of the lot, Safe Haven, indulged so deeply in the author’s sensibilities that it essentially became eye-rolling parody, right down to a twist that might have made M. Night Shyamalan snicker. The Longest Ride, on the other hand, walks right down the middle. This is another pretty little fairy tale designed to tuck the audience in at night and give them a warm glass of milk, but you can sense the storyteller just wants to get on with it and their mind is on other things.

Featuring two parallel love stories, Ride also has two pairs of lovers, a modern sort played by Scott Eastwood and Britt Robertson, and another, living more than half a century earlier, by Jack Huston and Oona Chaplin. Robertson, poised on the brink of stardom, is Sophia Danko, the quintessential city-girl—she’s going to college in North Carolina but heading out to an art gallery internship in New York City—who meets the expectedly laconic, charming and hunky country boy in Eastwood’s Luke Collins. To balance out the sensitive, thoughtful artist, Collins turns out to be a professional bull-rider, on his way to rehabilitating his career after a serious and side-lining injury he received by a bull named ‘Rango.’ The script plays coy with some of the plot details, but that kind of vague mystery doesn’t do much to distract from the fact that Luke and Sophia aren’t terribly interesting and their conflict, over whether to get serious in the face of geographic separation, seems rather trite. Of course, this gilded snow-globe universe throws them a bone in the form of Ira Levinson (Alan Alda), an old codger who has crashed his car on the side of the road, and is rescued by Luke on the way home from the big date.

The B-side of this story—far more interesting than Sophia and Luke—is concealed in a box of letters that Ira had with him in the car, read to him by Sophia as she sits by his hospital bed. In the past, Ira is played by Huston, and we learn of his great love, Ruth, an Austrian-Jewish refuge that he met prior to a stint in World War II, which sends him home unable to provide his wife with children. The typical tensions and obstacles mount, but here at least, the film takes on a certain emotional shape because of the performances of Huston and Chaplin, who have talent and energy and give a modicum of belief to the hackneyed scripting, which far too often resolves issues simply because enough run-time has passed, and it’s time to wrap things up. Alda exudes the expected warmth as the older Ira, and he neatly sells a character who, at this juncture of the story, is little more than a plot hook.

Of course, a large part of The Longest Ride is reserved for Eastwood, who has many of the same physical characteristics as his father, but not quite the same sense of presence that Clint possessed, even in his early roles. His chemistry with Robertson often feels forced, and the film all too cheerfully makes him beefcake window-dressing, there to be leered at bare-chested or bent over. Robertson is better, although it’s easier to appreciate her scenes with Alda, which forgo most of the romantic romping. The imbalance is that Sophia and Luke just aren’t ever as interesting, and the bull-riding elements—while seemingly a thematic focal point—aren’t particularly engaging or exciting, which capsizes most of the immediate drama.

Here, then, is where I take issue with the The Longest Ride, which may provide an unobjectionable date night outing, but won’t do anything new for Sparks fans or for skeptics; it’s just going through the motions. Director George Tillman, Jr. has done better with even sillier material—the Navy diving drama Men of Honor and the Dwayne Johnson revenge-thriller Faster come to mind—but he never approaches Ride with the courage of conviction. Every scene and sequence has been shot with an almost nervous awareness of its need to fit into some theoretical Sparks’ template. When this happens, those feelings of rehashed familiarity are hard to shake, and in the film’s worst moments, become actively irritating.

The Longest Ride wants us to believe that love is hard, human connection fleeting but precious, and that real intimacy is hard-won and rare, but then it turns around and so casually meanders down a cluttered road of clichés that you feel chided for daring to take a single ounce of it seriously. Forget the critics here; Sparks fans, who have managed to develop a taste for this sort of thing, are likely to find the flavor starting to get a little stale. Maybe it’s time to get Ryan Gosling back on the phone.

The Longest Ride is now playing in wide release.