It’s easy to map out the Dennis Hopper trajectory: mid-50’s/ -60’s classical Hollywood bit player to ’70s weirdo maverick to ’90s Hollywood-blockbuster villain — or even, in more succinct terms, hippie to Bush-voting Republican. Yet even if a morphing figure, there is a tendency to zero in on the brief iconoclast period: the counter-culture icon who, for one shining moment, had it all, only to be able to say — or rather to quote his most famous film — “We blew it.”

To draw another vital name from the long line of American cinema’s Icarus figures, as well as a friend and collaborator of Hopper’s, one can look no further than Nicholas Ray, a recent biography of whom attributed the subtitle “The Glorious Failure of An American Filmmaker.” This could serve as a one-line synopsis for The American Dreamer, a behind-the-scenes look at Hopper’s critical and commercial bellyflop of The Last Movie, his 1971 follow-up to the surprise smash hit Easy Rider.

Certainly Easy Rider’s you-had-to-be-there success becomes more and more of a mystery every year. After all, how could such a downbeat, experimental film capture the zeitgeist? It comes as even more of a head-scratcher how Universal Studios bankrolled something as utterly audience-alienating as The Last Movie, something that clearly stood no chance even with the burdening counter-culture.

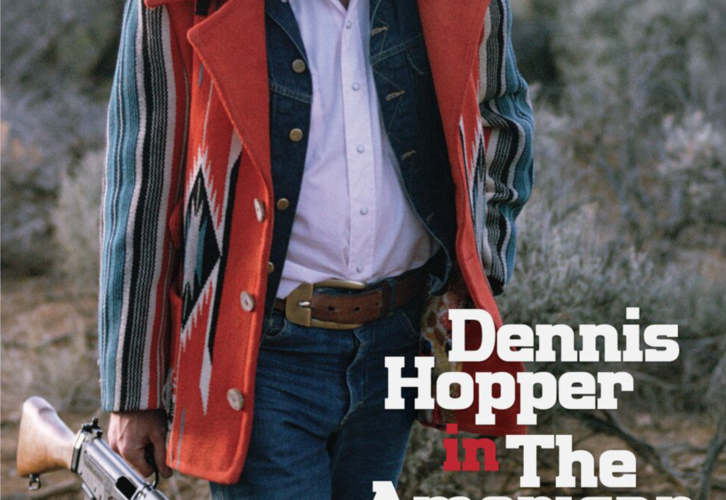

While at one point here Hopper is hounded by a studio executive to finally deliver a cut of the film, intruding on the fantasy of the artist, The American Dreamer seems less interested in depicting a man at work than one in a kind of leisure. Whether firing guns, making high-on-drugs-and-ego declarations (a common trait of ’70s auteurs) such as comparing himself to Orson Welles, there comes the impression of a man less making a film and more luxuriating and sinking in his own self-image.

He’s not far off from romanticizing his own self-pity: monologuing about the loneliness he experienced as a teen, his longing over starlets Leslie Caron and Elizabeth Taylor being enough to drive him to tears. But later in the film, surrounded by a number of naked women that he clearly exploits for the sake of his art, we’re not not simply seeing the dweeb attaining “coolness,” but a sense of a man playing for the camera at every moment.

Forty-five years removed, though, The American Dreamer certainly amasses a sentimental dimension. But the re-release doesn’t come off as simply another form of the aggressive ’70s Golden Age of Hollywood mythologizing that’s become rather tiresome in lieu of the recent blockbuster craze. Situated between critique and wake for Hopper’s ideals, perhaps we can optimistically see it as a reminder that the perpetual end-of-times cinema seems to be facing is actually what keeps it going, no matter the dangerous levels of hubris.

The American Dreamer is now available on VOD.