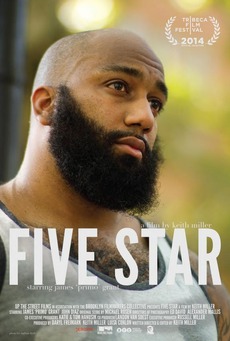

In Five Star, a film about a teenage boy named John (John Diaz) whose gangster father was killed by a “stray bullet,” John “Primo” Grant, a member of the Bloods gang, plays a dramatized version of himself. In the opening Primo is sitting in a car giving a monologue about how now, out of prison, it’s his responsibility to be there for his kids and his wife. As a “five-star” gang member and friend of John’s father, a kingpin himself, Primo is always treated with respect in the neighborhood, and in an early scene he agrees to take in John to teach him the same values. John, anxious to earn a little extra cash and perhaps learn a bit about his father, is more than up for running a kilo of drugs now and again.

Five Star is director Keith Miller’s second feature, after last year’s fresher, more authentic Welcome to Pine Hill, about a former criminal’s attempt at redemption. His follow-up, despite the teases of its opening, is less about Primo than it is about John, who sees Primo as the father he never had. But as the pre-title sequence and casting described above suggests, this is a gangster film devoid of operatic mainstays like power struggles and commentary on the American Dream and opportunity. Instead, everything is treated matter-of-factly, perhaps because the characters don’t know any other way of life, although even this interesting take on the gangster film does not undo the clichés or avoid the weaknesses in the screenplay.

In what may by Miller’s most unique and successful directorial choice, Five Star turns gang life into convention. The Bloods in Five Star are loosely structured, unintimidating, and only Primo is dangerous, a reflection of the attitudes of characters who don’t know the safer, more privileged life the film avoids. Participation is treated like a recreational instead of a major, often-times permanent lifestyle choice with consequences—Primo’s prison time is alluded to at the film’s beginning, but other than that, there is never any fear of consequence, and even suggestion is limited to a single plot-focused exchange.

These choices that highlight Five Star’s indie tropes nevertheless make sense for the film. Characters cannot begin to understand these circumstances, and if life on the streets is the only life they know, stripping away these gangster film tropes also creates a tone and mood that mirrors the characters’ mindset. Gang life here is not the dramatic, almost Shakespearean power struggle nearly all of the great gang (or more appropriately, mob) films evoke. Instead, Five Star’s approach privileges the viewpoint of its adolescent protagonist, surrounded by but never fully understanding the gravity of his situation. But without a great script, it also means that in spite of the intrigue created by the way the film navigates and even ignores the gangster genre, it is ultimately trapped by a different, larger set of clichés that make this virtue feel underexplored and accidental rather than integral.

Indeed, the film unfolds exactly as one would expect. John is somewhat quiet but not soft-spoken or nervous. He is charismatic enough, in fact, to win a girl over by talking to her about grizzly bears. When he isn’t working for Primo, he lovingly dodges his mother’s questions—if she is supposed to be the same overbearing and alienating force that Primo says led him to the streets, both the scripting and acting in these scenes fall well short of making that clear—and tries to assert his own independence. Miller’s approach to this material is low-key, as he shoots handheld and opts for somewhat longer takes than the norm, but not exactly non-invasive, as the close-up is the primary vehicle to draw the viewer in, a work-around to the lack of nuance and originality in story and character. Basic takes on redemption and coming-of-age play out just as one would expect by the time conflict arises (John’s mother learns what he is doing; John begins to question Primo), and easy questions about fatherhood/absence are invoked as one would expect.

Because of the heavy use of tropes, the documentary style and genre subversion (Primo’s family also play themselves) are not enough to make Five Star feel urgent or authentic. Miller’s world lacks the details of a fully lived-in one, and small but substantive details, such as, for example, the happenings in the park that the characters frequent, are missing. Furthermore, female characters allow themselves to be boxed into regressive archetypes, and the lack of choice and lack of family signposted in dialogue never show themselves in images or circumstance. In short, everything is too pat and neat: things go downhill without ever becoming grim, danger is suggested rather than felt, and the overall impression the film leaves is agreeable and even self-congratulatory rather than a profound or thought-provoking take on class, circumstance, crime, family, or anything else in the array of thematic choices the film gleans over.

Five Star will hit theaters on Friday, July 31st.