Life of Pi, Ang Lee‘s gallant, visually overwhelming adaptation of Yann Martel‘s bestseller, takes a little while to get going. The animals-are-precious opening credits, set to the most dangerously sentimental portions of Mychael Danna‘s mostly flexible musical score, made me immediately skeptical of the two-hour film that was to follow, and, continuing along that same cautious path, the first act of David Magee‘s (Finding Neverland) screenplay — burdened with expositional requirements that are dealt with through a forgettable, ill-treated device of narrative framing — is absolutely its weakest.

Watching some of these early sequences, which feature a present-day, adult-aged Pi (Irrfan Khan) reflecting on his life in the company of a Martel-like surrogate of sorts (Rafe Spall), you can virtually feel Lee‘s frustration behind the camera — this guy wants to get to the Pacific Ocean, and he wants to get there now. There’s a scene here where we learn that Pi’s full name, Piscine Militor Patel, was inspired by a swimming pool of the same name in France. (Pi, who’s played as a child by Ayush Tandon, has a lovable pseudo-uncle who’s a big swimmer.) Lee designs this French pool, as well as Pi’s uncle’s mystifyingly prominent muscular build, with such outrageous flair that his desire to let loose — to break free from the narrative set-up and unleash a bulldozing aesthetic experience — is palpable every step of the way.

That said, there are a good many Pi-related details we get in the opening act that will take on more significance as the film goes along. Much to the dismay of his father (Adil Hussain), who voices his science-trumps-religion philosophy on multiple occasions, Pi is an impressionable youngster who comes to embrace a handful of faiths — so many, in fact, that he’s told he may soon achieve the milestone of being able to live a never-ending religious holiday. And when Khan, as the eldest Pi, tells Spall‘s writer that his story will “make you believe in God,” we can tell that Pi’s childhood obsession with faith hasn’t vanished in the slightest. (Meanwhile, when lead-actor Suraj Sharma finally picks up the role of Pi, one of the first things we see him doing is reading Dostoevsky and Camus.)

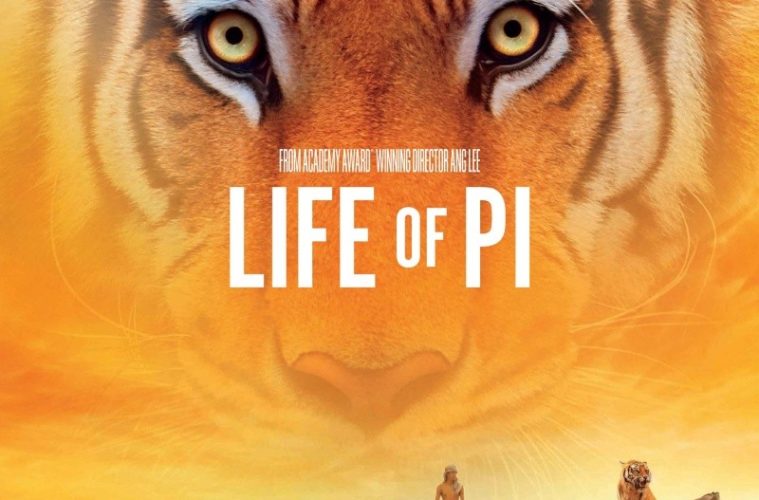

Which brings us to the Pacific Ocean. Pi’s father, having received word of a job opportunity in Canada, is uprooting his family from the modest Indian town of Pondicherry, and thereby relinquishing the existence of the family’s local zoo. Such a task, however, requires that the family’s collection of wild animals accompany them on their aquatic voyage. This makes the shipwreck that will soon hit the traveling boat all the more terrifying — in his frantic quest for survival, Pi will not only have to contend with stormy seas and fast-rising levels of water, but also the unpredictable presence of zebras, hyenas, and, most fearsomely, a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. (Yes, there’s a story behind that name, too.)

And, quite honestly, nothing else in the film can so much as hold a candle to the shipwreck sequence, which goes beyond the mere immersion factor that has distinguished other recent 3D accomplishments — Avatar, Hugo, etc. — and creates something with a concrete physical shock-value. Rather brilliantly, Lee, cinematographer Claudio Miranda, and the first-rate visual-effects crew don’t achieve the thrillingly smothering impact through quick cuts and agitated pacing — they do so through hauntingly lingering long takes, such as the one where Pi, paralyzed with fear, pauses underwater and simply stares at the results of the catastrophic collapse that has just taken place.

Impressively, the film doesn’t suffer a drop-off after Pi settles down on his raft with the few remaining creatures from his hometown zoo, because this juncture marks the moment when Lee is at last allowed to escape from his own expositional cage. Life of Pi is at its best when it’s functioning as a pure assault on the senses, and the ocean-set middle hour — complete with hallucinatory beauty, jaw-droppingly adorable meerkats, and a moving camaraderie between a boy and his tiger — is exactly that. Also among the atmospheric highlights is Lee’s experimentation with an underwater perspective — from the early, unbroken image of Pi’s uncle diving into a pool and swimming a lap, it’s clear that Lee has pinpointed a way to maximize the transfixing quality of that particular point of view.

These visceral triumphs aside, Life of Pi, despite its restore-your-faith-in-God narrative and openly sentimental attitude, remains curiously muted, the actors and situations struggling to achieve a thematic depth that can match the power and force of Lee’s images. If you’re familiar with Martel‘s novel, then you know that the story concludes with a bit of a surprise — but, confined as it is here to an extended speech, the potentially intriguing ambiguities therein are almost totally skimmed over. That doesn’t take away from the life-affirming demeanor that has been building from moment one, but it does keep the story from expanding itself into promisingly uncharted territory on the page.

It may be partly unfair, however, to shove all the blame onto Magee, because it’s largely Lee‘s own boisterousness that, in its own way, detracts from the emotion of the performances. This role is another major get for Spall, who was seen earlier this year in Prometheus, but in terms of contributing to the story and serving a legitimate purpose, his character’s barely even there. Khan, too, while provided with a few genuinely heartfelt lines, works more as a narrator than a human being. And though newcomer Sharma, boasting the most consistent screen time, may fair the best out of the bunch, the character of Pi, for me, never quite grew into anything beyond an ideological concept. Come to think of it, I may have liked Richard Parker best of all.

Life of Pi will hit theaters on November 21st.