Humanity gave birth to inequality. The American experience is rooted in institutionalized racial inequity. Our forefathers came to this nation either by choice or by force. Once here, this distinction coalesced into a convoluted caste system driven by notions of survival and supremacy, however primal, unfounded, and damaging. We are the result of these histories and our lives will stand as testaments to how much we can change and improve on them. By examining our prison industrial complex, Ava DuVernay’s 13th looks to the nation’s past, points to our present, and lays the stepping stones for a better tomorrow.

In 13th, DuVernay utilizes documentary standards to transcend standard filmmaking. The narrative is clear, forward, and thorough. Her “talking-head” interviews involve multiple angles, artful framing, and stunning backdrops. Interviewees range from Angela Davis (in an abandoned cathedral-like train station) to Newt Gingrich (on a staunch office couch), with a plethora of intellectuals and experts succinctly speaking to the audience from distinctly different locations, each backdrop bearing a purposefully industrial look. From D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation to the overwhelming amount of recent police brutality videos, DuVernay’s choices of film and archival footage are devastating, moving, and impactful. Intertitle transitions include lyrics from the film’s soul-striking soundtrack acting as both reflective reprieves and a way to drum the 13th’s impact further. The film keeps the audience attune to its pacing by way of a timeline of incarceration and discrimination-related statistics by decade.

On the spectrum of infographics-laden YouTube video to PBS weeks-long series, 13th stands somewhere in between as an incisive call to action for the information-age Netflix generation. Three years ago at the NYFF press conference for 12 Years A Slave (which is featured in 13th), Steve McQueen called for the need of a discussion about the ramifications of slavery in similar terms to how academics discuss the Holocaust and to how the public treats Holocaust survivors and their families. Two years ago, Ava DuVernay’s Selma sparked that conversation in terms that called for a reexamination — not only of the past, but the present, and became a cinematic cornerstone in #BlackLivesMatter. DuVernay’s 13th continues this discussion of the past and builds on it with an evocative exploration of the continuing injustice against a race in vital terms. As a human being, and especially as an American, you feel something about race, and 13th will make you want to do something.

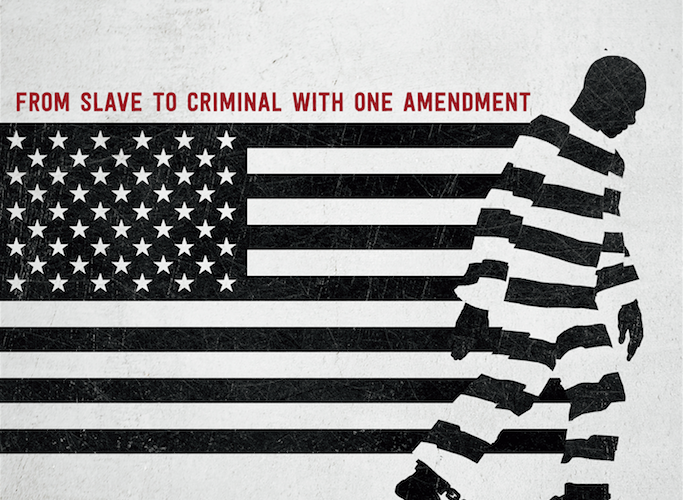

With its narrative interweaving of the past and present, 13th leaves one to draw the much-too-clear parallels from the near-century-apart tragedies of Emmett Till and Trayvon Martin to Trump bastardizing the already-damaging “Law and Order” language of Nixon. DuVernay presents history in such a way that the audience can’t deny its repetitiveness nor this country’s systemic persecution of black Americans. The long strain of this film, and American history, is the evolution of a terrible constant, that of slavery and its many forms. In spite of our diplomatic rhetoric, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” our nation was built on the backs of inequality white men created with power spawned from that abuse of and theft from fellow men. As 13th points out, this was and is perpetuated by a targeted legal system shifted from slavery to convict-leasing to Jim Crow to mass incarceration — or, as The New Jim Crow author Michelle Alexander puts it, “We haven’t ended racial caste, but redesigned it.”

Teaming up with Netflix after the success of Selma, DuVernay sought to make a documentary about the prison industrial complex and mass incarceration. With 13th, she has succeeded — not only in presenting the facts and figures, but also the life and scars of these issues. It isn’t just a corrupt system or people being thrown in jail and turned into cheap labor. It’s also families and communities being torn asunder for the sake of corporate greed and false white insecurities through a loophole found in Section 1 of the 13th amendment: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Examining both first and second source materials through a dynamic lens and the voices of educators and politicians, 13th speaks to a populace jaded by the status quo and encourages them to reexamine their own preconceptions and prejudices. This is a film that will unite us as a nation, or at least we of the Netflix generation, to have a productive discussion on race and racial injustices that, hopefully, will in turn lead to substantial, positive change.

13th premiered at the New York Film Festival and begins streaming on Netflix on Friday, October 7.