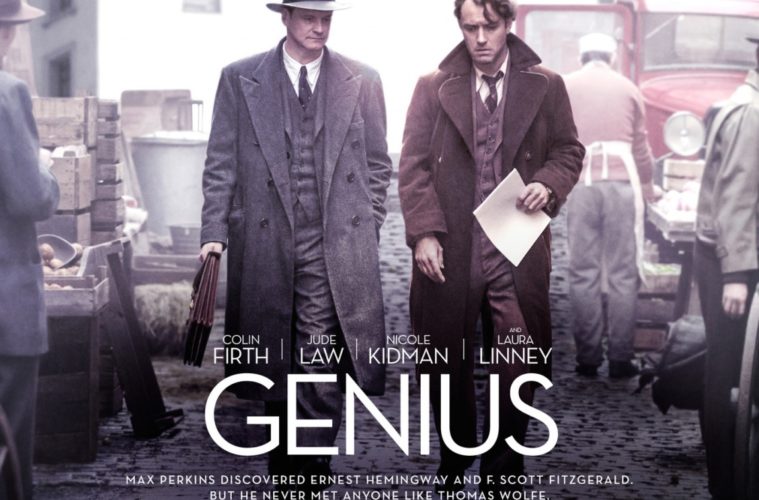

Genius is an exploration of the creative partnership between author Thomas Wolfe (Jude Law) and editor Maxwell Perkins (Colin Firth). Embedded in that quick synopsis are the challenges posed by the material: movies about books and writers can be met with cynicism or skepticism. Wolfe’s most notable work, novels such as Look Homeward Angel and You Can’t Go Home Again, are rich and mystifying challenges that elude easy adaptation. Given these potential challenges, it is impressive that Genius succeeds to this extent.

Michael Grandage‘s drama spans the birth and death of a relationship rather than the lives of its key players. Beginning with Max Perkins discovering the manuscript for Look Homeward Angel, the film layers Wolfe’s prose over the introduction to Max’s life. Max commutes on the train home and is greeted by his army of daughters but is never pulled out of the hypnotic trance that Wolfe’s prose holds over him. Among Grandage’s wisest decisions as a first-time feature director is to have faith in Wolfe’s writing as being compelling to listen to. There are many sequences in the film where entire passages of the work is read with no visual flair to accompany it.

In these opening moments Colin Firth sets the tone for his portrayal of Max Perkins. Relegated to the side, he relies on raised eyebrows or smirks to convey his response to whatever is happening around him. The character is so passive that it’s initially difficult to see where the drama can head without a driving force. Naturally, that force is the depiction of Wolfe. Law storms into frame in-character, all the way amped up, and rarely reigns it in from there. It’s a loquacious role for Law, who supplements all those words with wild hand gestures, stomps, and cackling.

Much will be made of Law’s performance. It’s showy and flamboyant in ways that invite comparisons to his work as the synthetic pleasure droid, Gigolo Joe, in Spielberg’s A.I.. Veteran screenwriter John Logan offers Law the best defense against those who find the performance grating. In one of this film’s more sober moments, Wolfe reasons that his showmanship and boisterousness are the very traits that made him a successful writer. Furthermore, Firth is a perfect foil for Law: he is quiet, introspective, and watches Wolfe with the same sobriety as the viewer.

Genius‘ runtime is mostly devoted to the collaboration between Perkins and Wolfe that shaped Look Homeward Angel and Of Time and the River. This narrow focus allows the film to develop its gentle comedic sensibilities regarding the ludicrous amount of pages Wolfe writes. It’s also leisurely paced in a way that many biographic films racing between key life events are not. In fact, peripheral material that surrounds the main drama can seem like a distraction. The film introduces F. Scott Fitzgerald (Guy Pearce) in a monologue about his mental state, and it bears the distinction of being the most over-acted moment. There’s also Aline (Nicole Kidman) and Louise (Laura Linney), the significant others to Wolfe and Perkins, respectively. Kidman has the difficult task of keeping up with Law’s insanity. It’s both the fault of the performance and the script that the character only seems necessary when tied back to Wolfe. She lambasts him, “You’re always in a moment of radical crisis.”

Ultimately, Genius is more satisfying than many recent traditional biopics, and, oddly, by embracing caricature-like portrayals, the film is able to tap into its simple but humble pleasures. There’s no lengthy debate as to what defines genius nor conversation as to what that even means; there doesn’t have to be. Genius puts those words right up on screen and the case is made.

Genius premiered at the 2016 Berlin International Film Festival and will be released by Roadside Attractions on June 10.