Screening in eleven curated programmes are thirty-eight international shorts and forty-four world-class homegrown Canadian shorts packed with strong emerging voices and unique perspectives. The compelling lineup encompasses works from filmmakers representing an impressive 36 countries. From provocative narratives to ground-breaking animation, from insightful dramas to profoundly moving documentaries, the works in Short Cuts showcase unique, yet universal, stories about the human condition, in short form.

Short Cuts is programmed by: Shane Smith, Director of Special Projects, TIFF; as well as Jason Anderson, Danis Goulet and Kathleen McInnis, Short Cuts Programmers.

UPDATE from TIFF:

On Wednesday September 16, for 24 hours, TIFF is conducting an experiment: our first ever online-only screening. We’ve curated a selection of international short films that are playing at Festival. But you don’t have to be in Toronto to see them – just buy tickets, log in, and be a part of the Festival from wherever you are. Tickets are onsale now. More details here.

Programme 1

Premiering Thursday, September 10th at 9:00pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• The Signalman, dir. Daniel Augusto, 15 min. – Brazil

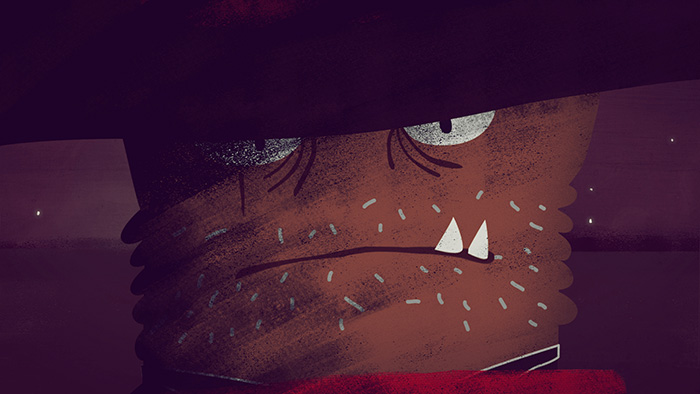

Writer/director Daniel Augusto definitely cultivates a dark tone for his short film O Sinaleiro [The Signalman]. Between the quiet isolation of the titular character (played by Fernando Teixeira) and the almost supernatural occurrences surrounding him, you can’t help but conjure ideas of some spectral evil looming at his door. The monotony of his job—logging an on-time train as just that—places him on a path towards psychological upheaval, transforming what we see into nightmarish hallucination as easily as believing it to be reality. Abstract and devoid of explanation, Augusto provides us something to sink our teeth into. But I’m not quite sure there’s much to decipher besides its aesthetic mood without a cursory knowledge of its source material. I admittedly found myself enjoying the short more after reading up on Charles Dickens‘ The Signal-Man for which it is based. Having the background of what this character is and his state on a subconscious level helps traverse the story’s path. Because watching his routine interrupted by an overflowing toilet achieves greater meaning in the depths the text gives us. As is onscreen it’s merely a bad luck circumstance to be cleaned up. The chance meeting with a mysterious gentleman on the tracks he operates taking place the same night as an accident is simply a strange coincidence. But his fear is real when translating the Morse code from another signalmen down the line despite the stakes not quite matching. The final scene therefore comes out of nowhere—a tragically horrific end that’s perhaps too vague. If I had read the story first I think I might love the adaptation. As a film on its own, however, I question how open-ended everything remains. The atmosphere is palpable, Teixeira’s performance authentic, and the art direction superb (the little matchstick men are great), but Augusto flips through them too quickly for my taste. His signalman’s fear amplifies with physical shaking and paranoia without introducing the cause as more than happenstance. The toilet trouble and the man on the tracks don’t necessarily feel scary as much as odd; the lack of witnessing the accident lessens its own impact as a warning for something more on the horizon. Only when I think about it in the context of Dickens’ text do I see the danger. I wish there were a way to see it on its own. C |

• Mobilize, dir. Caroline Monnet, 4 min. – Canada

One piece of a quartet entitled Souvenir—an anthology by Indigenous artists in Canada addressing Aboriginal identity and representation—ITWE Collective member Caroline Monnet‘s Mobilize proves an invigorating sort of time lapse look at the propulsion of life from hand-made disciplines in nature to the steel behemoths of modern cities set to Tanya Tagaq‘s “Uja”. Composed entirely of outtakes from the National Film Board of Canada’s archives of over 700 films, the staccato sounds resemble breathe heaving forward sharp and focused as snowshoes are strung before being used to walk in the woods for lumber which is cut and bent for canoes that bring humanity to civilization. It’s almost a music video playing on the tempo with an evolution of Aboriginals from forest to pavement. The cuts are extremely fast to work in tandem with the song’s beats and the innocuous is mixed with the exciting in the process. For every quick glimpse of axes chopping into tree trunks comes wonderfully composed footage of a canoe driver moving towards us with camera positioned at the foot of his craft. Scenes of steel workers moving girders cross against a fashionable woman walking below—a city sprung from the snow and swamplands that come previously. It’s a story of two halves everyone can relate to and a look at Canada through the eyes of a filmmaker twice removed from the visuals’ original intent. The idea of the Souvenir project is a captivating one and Monnet’s quarter a nicely conceived curio of socially charged nostalgia. B- |

• o negative, dir. Steven McCarthy, 14 min. – Canada

Sorry, Twilight. Your depiction of love between vampire and human pales in comparison to the uncensored drama of Steven McCarthy‘s o negative. This is the gritty truth of the type of co-dependent relationship such a union is constructed upon—one where morality and humanity is excised completely from matters of life and death. When your lover needs blood to survive you must be willing to forfeit your own existence whether it means feeding them from your vein or playing mother bird by acquiring an outside source and readying it for exsanguination. They are a junkie and you their last line of defense. But as with all pairings of the flesh, going further for them than you’d go for yourself proves an implicit term of the contract. The short is gorgeously shot by Cabot McNenly with an in-close, on-the-streets vibe of rapidly changing focus from soft to sharp for emotional enhancement. McCarthy himself plays the man willing to go to the depths of Hell for his girlfriend (Alyx Melone), wound up so tight he’s about to burst at any second. The camera captures his silent expressions and body language in accepting his fate, knowing of the prize that awaits him if only he can save her in time. We don’t know how she’s gotten this bad, just that it’s now or never in an expertly languid race against the clock. Too weak to take sustenance from his cut hand, a blood transfusion from vein to mouth is the last ditch effort they need to reset and recharge. Then comes the search for dinner. What’s great about McCarthy’s depiction is that he doesn’t gloss over the reality of the situation. It’s painted exactly like that of a drug addict and the blindness of love forcing someone to inject poison into their body to save them. It’s about doing the dirty work: whether murder, kidnapping, and theft or merely grunt work like washing blood off the walls post-feeding. We are slaves to those we desire to spend our lives with, caring for them in sickness and health because their wellbeing is the only thing keeping us alive. o negative shares a glimpse at this truth in its most grotesque, horror movie self. There’s no “thank you” necessary when death’s on the line—miracle save resulting from a heinous act or not. We’d do it again every time because love always justifies the means. A- |

• Paradise, dir. Laura Vandewynckel, 6 min. – Belgium

• 7 Sheep, dir. Wiktoria Szymanska, 21 min. – Poland/UK/Denmark/Mexico

• Never Steady, Never Still, dir. Kathleen Hepburn, 18 min. – Canada

A lot can happen over a very short period of time. We leave home to start new lives and things come our way that either allow the rebirth to flourish or stop it in its tracks. Sometimes we return to take care of family. Sometimes it’s for a lost love. Other reasons stem from being out of options. Kathleen Hepburn‘s Never Steady, Never Still deals with each of these examples converging on a small Canadian town as one boy’s homecoming helps reveal a mother’s resilience and a friend’s journey towards happiness. Pain, suffering, and regret all have the potential of being washed away by one smile; the hopefulness of another’s joy serving as evidence that it can happen to anyone at anytime no matter the bad luck or tragedy befalling him along the way. There’s a lot going on in these eighteen minutes and some plotlines appear incomplete as a result. With so many forks in the road, however, one leads to another and to remove it from the whole would be to weaken the remaining parts. It’s Jamie (Dylan Playfair) who has returned, walking the final stretch of road because his truck broke down, pushing his arrival to after mom’s (Tina Hedman‘s Judy) speech therapy session is complete. Their introductions have us anticipating the film as a depiction of familial love with a son giving back to a parent in a time of need—her ailment left unexplained. But Jamie is distracted, calling Danny (Parris JuRay) and leaving Judy in the middle of dinner to hang with him instead. This visit soon proving more involved than having a few days off. Home becomes a destination for repair to those who left (Jamie) and stayed (Mom and Danny). Relationships are revealed as more than appearances suppose, memories shared about people no longer with them to pull at emotions otherwise inaccessible by words. Life is shown as a complicated road full of obstacles—walls too tall to vault without help. Family, friends, and their love must be tapped as a source of strength and catharsis so smiles and laughter in the face of difficulty can exclaim that complexity doesn’t have to mean impossibility. The success of one works as the success for all because they’re each intrinsically connected via past, present, and future, together or apart. Everything happens for a reason, it’s how we combat adversity that truly defines us. And no one has to do it alone. B |

• That Dog, dir. Nick Thorburn, 15 min. – USA

Programme 2

Premiering Friday, September 11th at 9:45pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• People Are Becoming Clouds, dir. Marc Katz, 15 min. – USA

There’s a cute conceit at the heart of Marc Katz‘s People Are Becoming Clouds. John (David Ross) and Eleanor (Libby Woodbridge) have recently been married and ever since moving into a new apartment together have found she tends to transform into a cloud. Sometimes the type is in accord with her mood as far as color and lightning, others find her as distinct shapes like a dove playing a trumpet. In order to try and combat their struggle they seek Dr. Corduroy’s (Sean Cullen) assistance. According to him this ailment has become very common lately—a metaphoric nod to the hardships of a contemporary world where everyone has their own individualism to reconcile with their union to the person they love. A chasm has formed and its escape manifests as hiding under the guise of a meteorological anomaly. Katz’s decision to use clouds works because of their multi-faceted natures of proving soft and fluffy, confrontationally volatile, and completely open to interpretation. The latter brings an inherent humor as the psychiatrist nods an “ah-huh” whenever John describes Eleanor’s form. It’s as though he has a guidebook to what shape means what and cannot wait to have them come back once a week to describe each one. Unfortunately the absurdity of the situation is almost too much to bear and I found myself craving an explanation beyond being an acceptable oddity. Besides explaining it results from highly emotional circumstances—a sort of knee-jerk reaction to sensitive topics as a defense mechanism—it simply is. Sometimes that’s enough because the filmmaker builds off his rules and delivers weighty commentary above, but this time it needed more beneath the surface. I needed a breakthrough in therapy rather than introductory checklists. I needed broader humor to acknowledge the craziness of what occurs rather than sly smirks. The idea is wonderful and the characters embrace it whole-heartedly, but its execution through story lacks substance. Unfolding like the start of something bigger, a phenomenon taking everyone by storm (pun intended), it ends right when those answers appear ready to be revealed. We don’t see it happening to anyone else, no one freaks out when Eleanor changes, and it suddenly feels normal with nothing left to worry about. To me this shines depression and psychological disorder under a flippant light. Rather than seek to fix a problem or vocalize one exists, everyone laughs and airs frustrations until cloud metamorphosis becomes routine. Sadly, ignoring such pain and discomfort is the worst thing you can do. C |

• Wellington Jr., dir. Cécile Paysant, 12 min. – France

• Dogs Don’t Breed Cats, dir. Cristina Martins, 15 min. – Canada

• Dragstrip, dir. Daniel Claridge, Pacho Velez, 4 min. – USA

The Toronto International Film festival programmers are selling Daniel Claridge and Pacho Velez‘s short documentary Dragstrip as an “exhilarating blast of raw Americana”, but I’m not sure if it isn’t actually evidence of our affinity with the mundane instead. Shot at the Lebanon Valley Dragway in Upstate New York, the film captures a slice of racing life in static shots aurally filled with the roar of engines and voice of a loudspeaker. We don’t actually see the cars in motion, but rather the drivers in anticipation and spectators following the track with heads moving left to right in tandem. It’s the glorification of the banal—a visual representation of America’s hobbies being less about the event than our reaction to it. I feel the same sense of boredom I experienced the one time I went to a racetrack because the filmmakers portray it without filter. To me the most exciting aspect was watching how excited and involved those around me were—wondering if they would be as ambivalent to the main event of something I was passionate about as I was of this. The sense of awe in their voices and eyes following a bunch of cars in circles is a captivating sight. It makes you want to enter their minds to understand exactly what it is that so entrances them. Dragstrip therefore goes beyond Americana into mankind’s psyche on a grander, purer scale. A ritual so barebones and devoid of Nascar’s bells and whistles, the sport itself hits them in a way I’m envious to replicate. B- |

• It’s Not You, dir. Don McKellar, 12 min. – Canada

• Barbados, dir. Misha Manson-Smith, 7 min. – USA

• Blue Spring, dir. Andreea Cristina Bortun, 15 min. – Romania

• Maman(s), dir. Maïmouna Doucouré, 21 min. – France

Young Aida (Sokhna Diallo) is forced to process a lot on the day her father (Eriq Ebouaney‘s Alioune) returns to Paris from Senegal after two months away. First is the joyous laughter of mom (Maïmouna Gueye‘s Mariam) and her friends burning an herbal aphrodisiac up her dress. Next is the happiness of seeing him finally walk through the door with love and an embrace. Before anyone can get too excited, though, smiles turn to confusion at the fact he hasn’t come alone. With him is Rama (Mareme N’Diaye), baby in arms. The audience and Mariam infer rather quickly what this situation entails, but Aida isn’t quite sure. Does her father not love her mother anymore? Who is this stranger? And why is mom so distraught? These are the conditions writer/director Maïmouna Doucouré thrusts upon this eight-year old character in Maman(s). The whole is shown from her vantage point—the curiosity, bewilderment, and anger evolving one to the next as snippets of dialogue and interaction is gleaned throughout each day. Her brother (Azize Diabaté Abdoulaye) is practically unfazed, happy his dad is back and possibly thinking about the prospect of two wives in his own future. What we’re watching is obviously a patriarchal union for Rama to even be let into this house and Aida is officially opening her eyes to what that means. The newcomer has her own container of incense that’s bigger than her mom’s, so maybe that’s the issue. What begins as innocent disobedience in a show of loyalty to Mariam, Aida’s frustrations begin to mirror the scorned wife until she tearfully takes drastic measures. You can’t even really blame the child because she hasn’t been prepared for the difficulties of life through unknown circumstances. Mom and Dad aren’t quick to lift the curtain so soon, but shielding her from the truth of the emotions and anger they feel only amplifies their effect. Doucouré says a lot with very little, putting us in Aida’s shoes to witness her mind reading this betrayal as simple black and white. There’s so much more happening on the fringes, though, yet all she sees is an intruder. What’s therefore a quicker route back to normalcy than excising it? B+ |

Programme 3

Premiering Saturday, September 12th at 7:00pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• A New Year, dir. Marie-Ève Juste, 11 min. – Canada

• Boxing, dir. Grayson Moore, Aidan Shipley, 13 min. – Canada

• Semele, dir. Myrsini Aristidou, 13 min. – Cyprus/Greece/USA

As children we crave time with our parents—especially when quality family outings prove few and far between. The titular Semele (Vasiliki Kokkoliadi) in Myrsini Aristidou‘s short film will do anything to force some face-to-face, even going so far as hitch-hiking her way to the carpentry plant where her father works to acquire his signature on a school form. Mom’s nowhere to be seen and who knows how long it’s been since Semele and Aris (Yannis Stankoglou) were even in the same room together considering a query about getting pizza for dinner is met with a drag on his cigarette and the declaration he has to go back on the clock. It’s amazing to think such uncertainty and isolation could render a quick trip to the convenience store the best part of a little girl’s week. Semele is above all else a wonderful character study with two great performances lending a complex range of emotions to what would otherwise appear to be an innocuous situation. To see Kokkoliadi’s smile and genuine excitement at being with her father during the day and somewhere he cannot escape is to also she the pain and suffering their distance has built. Stankoglou’s blank face of shock noticing her in the corner while slicing through blocks of wood gives us all we need to know concerning the stoic nature that puts her out of sight/out of mind. She has intruded upon a part of his life that he takes care to separate and he’s quick to usher her away. Not because it’s a dangerous place, he just isn’t prepared to be her father in this venue. As soon as Aris shoos Semele to “stay put and not move” we know something will occur to make him confront the merging of these worlds—to tear down his armor and show her the love he doesn’t often share. Glimpses of playfulness and treating her as an equal when engaged in petty larceny proves it’s possible, but showing anger rather than worry for the girl’s journey risks ruining any good will such moments construct. Sometimes we need the smallest of gestures to negate our loneliness—a simple acknowledgement that we exist as more than a chore. It’s easy as a parent to forget this until a moment arrives where the child’s well being becomes paramount to everything else. If you’re to be ignored anyway, what’s the harm in risking injury in the hope they’ll finally see you? B |

• Deszcz (Rain), dir. Malina Maria Mackiewicz, 5 min. – Australia

• Bacon & God’s Wrath, dir. Sol Friedman, 9 min. – Canada

I apologize to both my grandmothers because Razie Brownstone is my new hero. Kosher for 90 years of life, it was a journey through “the Google” by way of “the internet” that shook her faith. All the questions she never thought could be answered suddenly became available with a few keystrokes—sometimes Google even anticipated exactly what she wanted to ask. We’ve all fallen down rabbit holes of information overload and alternative opinions infiltrating our brains to cement themselves as core belief, but it’s something else to see nine decades of devout practice brought on by strict parents and even stricter grandparents simply disappear in an instant. With so many religions and such crazy reasons for things blindly held as gospel, how could she not take a step back? How could she not willfully try bacon for breakfast? It’s a cute idea for a documentary and Sol Friedman cashes in on the simplicity of Razie’s endearing personality to make Bacon & God’s Wrath an enjoyable look at how quick we are to adhere to tradition without fully understanding the “why”? His subject is amazing—the definition of adorable and smart as a whip. She knows exactly what she’s doing and is fearless about the consequences. After all, how real could a punishment suffered by her great aunt at the hands of a town full of angry orthodox Jews be—a retribution too horrible to share—for something so small as eating a non-kosher item? Is bacon really so blasphemous if people devour it the world over? Is it worth worrying whether God will strike her down at her age anyway? Beyond Razie’s intrinsic likeability, Friedman has fun with the proceedings by animating her history and bringing things like an electronic tablet and a boar’s head to life. Even the static shots of Razie relaying answers to his questions are done with intrigue by playfully filming her lying down. You’ll think the whole endeavor is something to laugh at going in with such senior citizen chestnuts as adding “the” to every unknown thing, but the truth is we actually laugh with her or not at all. Razie commands our respect and our attention, preaching a realization that faith and God might have no bearing on anything earthly at all. And when these thoughts come from a woman who’s lived a charmed life in Judaism’s good graces, its inspiring to see reason stop her rather than go on believing it’s been God’s doing and not hers all along. B+ |

• The Ballad of Immortal Joe, dir. Hector Herrera, 6 min. – Canada

Written in memory of a family member, Pazit Cahlon‘s Western poem The Ballad of Immortal Joe sounds like a nursery rhyme but plays like a bittersweet romance of cursed love. Directed and animated by Hector Herrera, the short has an eye-catching aesthetic with dark palette and deep gradients atop playful characters straight out of the opening credits to Monsters, Inc. Some figures have six eyeballs, others four legs, and all are a little left of center in an imaginative way to engage children with wild art while also touching adults with its melancholic tome. Music by The Sadies enhances the mood and we listen as Kenneth Walsh‘s narration shares with a stranger in the desert the titular hero’s tale of woe. The lyrical nature of the work sticks with you as well as its message of being better for those no longer here with us. Flashbacks of why Joe wanders alone under the crescent moon weave in with a campfire of today as decorative script illustrates words from the deceased telling him to carry on his fight to defend the defenseless for all time. Sung in the tradition of Robert W. Service—of whom I am sadly not familiar—the piece hits you in the heart and soul before it’s done. There’s beauty to its sorrow and magic to its style, uplifting in its embrace of tragedy as a way towards redemption and honor. A hard-edged Dr. Seuss song with weight and drama, Cahlon and Herrera’s collaboration is one you won’t want to miss. B+ |

• Following Diana, dir. Kamila Andini, 40 min. – Indonesia

Programme 4

Premiering Saturday, September 12th at 10:00pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• Casualties of Modernity, dir. Kent Monkman, 14 min. – Canada

• World Famous Gopher Hole Museum, dir. Chelsea McMullan, Douglas Nayler, 20 min. – Canada

• Peripheria, dir. David Coquard-Dassault, 12 min. – France

A post-apocalyptic wasteland born from an abandoned council estate of mammoth cement structures covered in graffiti and devoid of life—human life—David Coquard-Dassault‘s Peripheria showcases an aftermath of the unusable imprint we’ve made on Earth. Without our species to use these homes for dwelling or canvases, they merely stand reflecting the sun as large shadow makers for the creatures still roaming below. The dogs are what’s left, feral and awake. They rule the land with teeth bared, claiming property and possession as the owners cooped up in 10,000-plus habitats piled on top of one another used to as well. But instead of the buildings’ doors and windows providing shelter and safety, they’ve become methods of imprisonment and death sentences since the current tenants are without the means to escape. The animation on display is a memorable aesthetic of roughly textured colors forming familiar shapes, each shimmering along with the passage of frames moving forward. Only the black dogs cutting silhouettes against the graying façades and some plastic bags floating in the wind move to prove it isn’t static photographs progressing through a slideshow by moving film documenting time. The homogeneity of the breed and fur color breaks these animals down to their species—something humanity still refuses to do with racism and bigotry alive and well. As we see them snarl and claim stakes, though, it makes you wonder if peace is an impossible ideal no matter differences or similarities pulling us apart or pushing us together. We will always want, destroy, and want more before repeating the cycle until nothing remains. Coquard-Dassault setting is proof—deserted by mankind or left after murdering itself into oblivion. All we’ve built will remain useless and damning, evidence of our failures. The dogs will soon join us, segmenting themselves into groups locked in high-rises without food or trapped in dry pools to clutch onto what’s left of their identities before starvation claims victory. And just as we think we know their fate is identical to our own, Coquard-Dassault and co-writer Patricia Valeix throw a curveball. Maybe this isn’t a memorial to humanity, but a shrine to a past long since forgotten and ready for rebirth. Maybe it’s a sign of our wastefulness and hubris, to take the Earth, abandon it, and rebuild. Maybe its emptiness shows our self-anointed power to mold nature in our image, burning everything standing against our vision of glory. B |

• Beyond the Horizon, dir. Ryan J. Noth, 8 min. – Canada

• Boy, dir. Connor Jessup, 14 min. – Canada

• Beneath the Spaceship, dir. Caroline Ingvarsson, 15 min. – Sweden

What’s the age cut-off for friendship? It’s an interesting notion to consider because at a certain point a noticeable difference becomes intrinsically pedophilic in the eyes of society. Where a neighbor can befriend someone young as a babysitter, alternate parental figure, etc., as soon as the child hits puberty the platonic nature of the relationship changes. From inside it’s the same because the years have merely gone by. From the outside, however, what would have once been ignored becomes scrutinized. And while the adult has the maturity level to understand it will always be a harmless union, the child isn’t so stable. Not only could his/her sense of friendship grow into a love of respect and possibly convenience, but the quick ridicule from others his/her age will also threaten to instantly taint his/her own mindset. This is the philosophical and emotional dilemma at the center of Caroline Ingvarsson‘s Beneath the Spaceship. It depicts this change on a seemingly innocuous day like any other where Julie’s (Selma Modéer Viking) mother allows her to visit Paul (Per Lasson) across the way. She arrives to cut his hair for the payment of his taking her out in his car for driving lessons. It’s a day that wouldn’t demand a second glance had it been a teen and her father or uncle. It doesn’t garner a second glance from us either until Julie’s innocence travels too far. Drawing a map on Paul’s leg, she approaches a realm that’s hardly appropriate. But while his surprise and horror cause him to jolt up and walk away, you wonder if he’d have reacted the same two years prior. Is it because Julie’s no longer youthfully androgynous? Does Paul himself aroused or fear she might? While a minor hiccup exposing the cracks in society’s microscopic gaze upon them, it’s still a personal development space and time can heal. When Julie’s older cousin (Vala Norén) projects sexuality on them to make the young girl uncomfortable by blatantly flirting out of interest or the playful desire to make her jealous, however, the entire affair blows up. The awkwardness of Paul joining these teens for a day by the water causes he and Julie to wish the Death Star they joked about destroying Earth so they could start anew would come. It does to an extent, but not the way their idyllic natures originally hoped. Their new beginning staring back potentially becomes one where they can never be together again. B+ |

• Portal to Hell!!!, dir. Vivieno Caldinelli, 11 min. – Canada

Programme 5

Premiering Sunday, September 13th at 7:00pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• New Eyes, dir. Hiwot Admasu Getaneh, 12 min. – France/UK

• KOKOM, dir. Kevin Papatie, 5 min. – Canada

• The Magnificent Life Underwater, dir. Joël Vaudreuil, 16 min. – Canada

• The Society, dir. Osama Rasheed, 13 min. – Iraq/Germany

• She Stoops to Conquer, dir. Zack Russell, 16 min. – Canada

The TIFF description calling Zack Russell‘s She Stoops to Conquer a “fantastical oddity” is about as spot-on a review as you can get. What else can you say about a short film depicting a struggling performance artist who applies a latex mask—transforming her into an older gentleman in hope of laughter that doesn’t come—who comes face-to-face with the alter ego in real life? The possibilities are almost nightmarish: to see yourself in parody and wonder what sort of game is happening around you. There’s a horror film beneath such a conceit and yet Russell and co-writer Kayla Lorette (who also stars) go for rom/com instead. It’s a bold move that renders the piece even stranger, but I cannot deny its appeal for the very same reason. We’re dropped into the world with little bearing other than knowing the initial locale is filled with young girls putting on costumes to entertain the masses. But while most don fake sideburns and moustaches to dance onstage in a drag show as men, the forlorn Lorette sits at her mirror applying a full prosthetic. The performance meets with much less enthusiasm than the others so it’s unsurprising to find her even more withdrawn afterwards, smoking alone in the alley. Something about the light and music emanating from a different underground venue draws her over, still in costume. It’s there she meets Julian Richings—a perfect doppelgänger of her professional persona. Rather than be appalled or scared, however, he engages her in a conversation of movement. They become one against the music. The whole project is eccentric like this: both characters literal mirrors of each other who embrace the coincidence and become more self-assured in their bodies than perhaps they’ve ever been before. The relationship forged is off-putting not for the age difference, but for the idea of twins arousing each other being a disturbing sight. There’s a transference of confidence and identity between them that brings us to a finale equally exploitative as it is sweetly dignifying. Awkwardness in the morning replaces the stupor of alcohol and excitement as one self is destroyed so another can rise from the ashes. Whether the interaction was real or dreamed, the end result is a newfound success of authenticity that speaks to the audience. Only when she believes her character is authentic can those watching do the same. B- |

• Remaining Lives, dir. Luiza Cocora, 17 min. – Canada

• El Adiós, dir. Clara Roquet, 15 min. – Spain

I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of servants in this day and age. Money notwithstanding, just thinking about sitting at a dinner table and asking someone to do something you could have completed in the time it took to ask is impossible to fathom. Add the dynamic of an entitled secondary employer and the whole thing becomes even less so. Clara Roquet‘s El Adiós takes great care to show just how much the deceased matriarch of this wealthy Bolivian family meant to their maid Rosana (Jenny Ríos) and yet the woman’s daughter (Mercé Pons) remains oblivious. So intent on ensuring everything’s perfect to her tastes, Mercé can’t comprehend how a hired hand would care to do anything but what she’s told. Truth be told, Rosana was probably more of a daughter than she ever proved beyond blood. The film’s full of presumptions on behalf of Mercé—ideas only someone out of touch with the real world could believe. To her Rosana knows nothing else so it’s assumed she’d simply carry on her work with the next generation, helping maintain her household and raising her daughter Júlia (Júlia Danés) no questions asked. It’s this certainty in Mercé’s actions and tone that make you want Rosana to smack her in the face, but this working class woman is too spiritual and mature for such behavior. Instead she simply nods in acquiesce at each turn, smiling when Mercé orders her to change her mother’s burial attire from red to white for selfish reasons. Rosana knows her late employer wanted the red and she’s going to honor that wish. This is her memorial after all, not Mercé’s coronation. Ríos is fantastic, stoically heartfelt and caught in a world that’s doubled as her personal and public realm. She worked in the house, but was also a human being we infer her boss treated with respect and equality—enough to leave Rosana with the desire to witness her being laid to rest. Rosana’s the one who compassionately follows routine on such a grievous day, bottling up sadness to do right by the woman everyone else arrives to remember. The sense of entitlement from Pons is therefore enough to send you into a rage. While this is the environment in which she grew, she doesn’t have the right or place to blindly set this employee’s future as though property. Witnessing Rosana’s composure proves inspiring, her loyalty reaching just far enough to fulfill her duty to the deceased. No more. B |

Programme 6

Premiering Sunday, September 13th at 9:45pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• NINA, dir. Halima Elkhatabi, 15 min. – Canada

• Overpass, dir. Patrice Laliberté, 19 min. – Canada

Writer/director Patrice Laliberté‘s short film Overpass relies heavily on our suppositions as the viewer. And it does so to perfection. To us Mathieu (Téo Vachon Sincennes) has done nothing to earn the benefit of the doubt. Not only do we meet him sneaking out to illegally spray paint a bridge over the nearby interstate, he’s willfully difficult with his parents as a rule at home. He smiles when he escapes imprisonment and projects can’t-be-bother frustration when his mom (Sandrine Bisson) asks him to simply close cabinet doors once he’s done getting what he wants. Mathieu is the consummate seventeen-year old troublemaker defacing property and smoking weed—a lost cause. We’re not supposed to sympathize with him; we sympathize with those he lets down. His avoiding Dad (Stéphane Jacques) is probably the result of the latest thing he’s done wrong and his mother asking for him to return home by 3:30pm so he can travel to the airport for his brother’s arrival virtually assures a fresh example of disappointment positioned on the horizon. This is the environment Laliberté introduces: a nice up-standing family with an unreliable black sheep always one step away from ruining his life and theirs in the process. And for what? To paint some lewd remark the city can laugh at on their morning commute? You almost wish Mathieu’s mother would have told him to stay with his skateboarding friends and just skip the airport altogether. She can’t be let down if there are no expectations. Overpass is not that easy, though. Surfaces are deceiving—to a point. Mathieu is obviously a delinquent, but perhaps he isn’t so out of touch with the emotional gravity of the situation his family finds itself in the midst of enduring. Laliberté somehow pulls his strings so that we think the worst of his lead character, but we never see his fingerprints until the end. The journey is natural and authentic from the long take opening of Sincennes walking with plank and paint in hand down the street to the meaningless chatter about chicken fingers enjoyed by his stoner crew. The boy’s ambivalence and juvenile sense of resentment are so relatable to our own youthful experiences that we can’t tell they’re actually hiding grief. What’s at once a neo-realist account of a punk kid wreaking havoc turns on a dime to a heart-breaking look at loss and how we all cope in our own personal ways. Whether it’s taking our minds off what’s coming by cleaning the house, silently working away in the yard so as to not breakdown when melancholic thoughts interrupt idleness, or utilizing a creative outlet to pay tribute to the fallen—nothing strips us down to naked emotion and thusly catalyze an attempt to camouflage like death. In this manner everything Laliberté supplies is smoke and mirrors and boy does a few seconds of Jacques in the rearview mirror reveal the stunningly poignant truth. Life is full of surprises from the unlikeliest of places. A |

• The Sleepwalker, dir. Theodore Ushev, 4 min. – Canada

Animator Theodore Ushev embraces yet another visual style to treat us with at the Toronto International Film Festival. From conté crayon images rotoscoped atop Jafar Panahi in 2012’s Joda to the Cubist/Constructivist homage of 2013’s Gloria Victoria, his latest The Sleepwalker delves into Abstract Expressionism bearing to mind an amalgam of Arshile Gorky’s painting and Alexander Calder‘s mobile sculptures. It’s all geometric shapes, mostly with curved edges, each dotted as though fabric sewn with seams collaged and brought to life in a gyratory dance to Kottarashky‘s infectious Balkan beats. Oh, there’s a bit of Federico García Lorca‘s poem “Romance Sonámbulo” too. It starts with the last line of the first stanza “Under the gypsy moon, all things are watching her and she cannot see them” before the biomorphic shape of a woman on her balcony looks out onto a world peering back. She folds into the black void of the frame shortly after as the repetition of figures pulsing and flowing together or in sequence, multiplying and moving to the music, mimics the cyclical nature of the poem. Some forms resemble discernable objects from life and others are closer to cellular organisms floating around invisible to the human eye. And just when we think it’s merely a fun music video, the woman returns in a different form—metaphorically there watching, but forever blind to see. B- |

• Dream the Other, dir. Abril Schmucler Iñiguez, 16 min. – Mexico

• Violet, dir. Maurice Joyce, 8 min. – Ireland

• End of Puberty, dir. Fanni Szilágyi, 13 min. – Hungary

• One Last Night, dir. Kerem Blumberg, 22 min. – Israel

Despite many aging punk rockers going strong—or maybe they’re the punk poppers—the punk-rock game is for the young. It’s easy to be anti-establishment and anarchist when life has yet to drag you into its tractor beam of responsibility. To party all night and not worry about the consequences an evening in jail brings isn’t something you can sustain into your late-twenties when life replaces fun. Noa (Michal Korman) understands this because she finds herself at a crossroads between following love for love’s sake or contextualizing her next step with what she desires for herself. Orr (Agam Schuster) knows what will bring her personal satisfaction and the fact she’s willing to leave Israel for Berlin to find it without her girlfriend says volumes. But maybe all Noa really wants is Orr. Maybe following her is enough. This is their One Last Night, a hopeful evening of fun and romance to hold them over until Noa can join Orr at year’s end. Whereas the latter’s excited about what the next day holds, the former can’t help feel pained. It alters her sexuality in bed and prevents her from seeing anything around her except the want to spend as much time together as possible. So when they finally agree to leave their local bar for home, Noa is desperate for Orr to ignore an acquaintance named Dima being harassed by the police. Nothing good can come of an altercation and she knows Orr’s interference will merely press pause on the inevitability of this troubled friend’s incarceration. But ignoring isn’t what Orr does—she runs headfirst and worries about the fallout later. Written and directed by Kerem Blumberg, this short depicts the compromises we’re willing to make to achieve our goals. Whereas Orr seeks to stand up against a government for what she construes as wrongdoing—enough to leave town for good—Noa strives to stand up for the person she loves no matter the damage to others. Whether one is more just than the other is up to you to decide as there’s a case for Orr going home with Noa to move on with their lives as well as one for her to stay true to who she is without backing down. Where things get blurred is when one begins to make the other’s decision for her. The takeaway being that selflessness will always be motivated by selfishness. The question is whether you’re able to accept that realization. B- |

Programme 7

Premiering Monday, September 14th at 6:45pm | TIFF Bell Lightbox

• Never Happened, dir. Mark Slutsky, 8 min. – Canada

For eight minutes Mark Slutsky makes sure he has us right where he wants us. Never Happened is so precisely measured in its construction and revelations that we don’t even know its true genre until the very end. Yes there’s comedy and romance and drama in its plot concerning two business partners engaging in a sexual relationship while out of town for a meeting, but their decision to forget the encounter brings with it a much larger understanding of the world in which they live than merely lying to your spouse exposes. And if that’s not enough Slutsky goes even further with a final shot causing us to wonder exactly how much of the lives these characters live is actually being lived for the first time. The movie obviously attracted a recognizable cast with TV stars Mia Kirshner and Anna Hopkins from Defiance and Aaron Abrams from Hannibal because of its well-executed twist and the deceivingly meaty roles it provides. Abrams’ Grady and Hopkins’ Sharon go about their reunion at home like nothing happened while his recounting the lie mixes with flashbacks to the truth between he and Kirshner’s Laura. A lot of the short’s success stems from his performance, flipping back and forth from fact and fiction to really have us buy his deceit and hate him for what he’s doing. To eventually learn why he’s so good at it should make us despise him more, but the brilliance of the circumstances impresses instead. After all, if no one knows that it happened, did it really? B+ |

• Benjamin, dir. Sherren Lee, 16 min. – Canada

Very few things are more dramatically impossible to fathom than losing a child, but Sherren Lee‘s Benjamin goes one step further to make it so. Written by Kathleen Hepburn, the story centers on a lesbian couple—both of who are pregnant. Sophie (Kimberly Laferriere) carries their little girl while Dell’s (Joanne Boland) boy is promised to their best friends, Teddy (Jean-Michel Le Gal) and Cal (Jimi Shlag). Everything moves forward perfectly until pain suddenly runs through Sophie to ensure nothing can remain the same. The loss is staggering and all four feel it. What then can be done? For months Teddy and Cal have held Dell’s unborn boy as theirs just as she had. But while giving him up wasn’t a problem when she knew she’d have a child of her own, that was no longer the case. What transpires is an emotional roller coaster from joy to sorrow to hopeful optimism to absolute depression. The dialogue and attitudes are one hundred percent authentic whether Cal admitting to his husband that he was relieved the baby they agreed would be theirs didn’t die instead or Teddy’s complete inability to hear the girls’ trying to explain why they needed to void the contract they drew up. It’s all the more moving courtesy of the relationship this quartet shares too. This isn’t some womb for hire where lawyers or adoption agencies can get involved—this is for all intents and purposes family. The agreement was made because they’d all be in both children’s lives. The fact one would live with the girls and one the boys wasn’t so regimented an idea until only a single child was left. The performances are powerful; the circumstances unlike anything you could imagine. Anger enters the equation even if everyone knows they’re all only doing what they feel they must. Heads are simultaneously screwed on tightly towards each other but fully dislodged in a blindsiding nightmare where the baby is concerned. There’s a fine line between not letting Sophie blame herself for putting them in this situation and Teddy’s curse-laden rebuttal consisting purely of raw emotion. Devoid of a correct answer for what to do next, no one can fault anything but bad luck for the current predicament. They all know the girls are being selfish, but don’t they have a right to be? And if they all truly love one another, is there really a choice? Pain is unavoidable—the question is whether the child can be spared it. A |

• Exit/Entrance or Trasumanar, dir. Federica Foglia, 7 min. – Italy/Canada

• (Otto), dir. Multiple Directors, 10 min. – Netherlands

Writers/directors/animators Job, Joris & Marieke may be my new favorite computer animation team. Unlike Pixar or Dreamworks, however, I’m not sure I’d ever want them to go feature length since their style is so perfectly suited to the short form. Their Oscar-nominated A Single Life was my first introduction to them as well as my hopeful for Academy glory before their eventual defeat to the equally brilliant Feast from a rejuvenated Disney Studios. The character design is far from realistic and perhaps unattractive in a conventional sense, but it’s unique and gets the job of carrying profound emotional stories to fruition down. With (Otto) I can safely say their success was no fluke. Not only does their latest continue to pull at heartstrings, it also showcases some expert camerawork to tell its tale without words. (Otto) travels between two parallel threads that converge once in the middle and again at the end. Thread One deals with a young couple desperate to discover their lack of conceiving a child has been due to bad luck as opposed to faulty biology. Thread Two shows a happy-go-lucky girl who plays patty cake with her titular imaginary friend. As the would-be parents withdraw from their news it’s this little girl who brings a smile to the woman’s face. They are all at a diner and the youngster is jetting around with the giggles in a game of hide-and-seek. The woman watches with bittersweet joy, playing along as her husband rolls his eyes in self-pity and frustration. Wanting this fun to never end, she does something you wouldn’t expect. She takes Otto home. What follows is super cute in that Otto is completely invisible and yet fully realized in the woman and girl’s minds. As soon as the former takes him, the latter can’t find him. Job, Joris & Marieke take painstaking care to ensure we know exactly where he is at all times, though, with low vantage points and determined pans. The characters we do see are all extremely expressive with succinct gestures and authentic emotion on a road towards finding exactly what each desires. The journey has some fantastic flourishes like an adorable mean streak from the girl once she discovers the truth of what happened. And in the end it’s up to imagination to provide the couple an escape from the depression of their circumstances. Love is not only for families and families aren’t only built through pregnancy. A |

• Mia’, dir. Amanda Strong, Bracken Hanuse Corlett, 8 min. – Canada

• Rock the Box, dir. Katherine Monk, 10 min. – Canada

The story Katherine Monk brings us in Rock the Box isn’t necessarily unique when you only have to look at the Pop charts to see Miley Cyrus—or Lady Gaga to a more art-house abstraction—doing much of the same thing. What’s different between them and Rhiannon Rozier (DJ Rhiannon) is that EDM (Electronic Dance Music) is far from the same universe as Pop. While it’s become the biggest moneymaking sector in the industry, its not-so-radio-friendly tunes and messages keep it from gaining the mainstream exposure those other artists have at their fingertips. So this straight-A honors student turned DJ couldn’t simply take her “mask” to MTV or the Grammys and cause a publicity stir. No, Rozier had to go to Playboy. To hear her tell it as she’s applying make-up for a show is to fully understand how conscious a decision this career move was. EDM is 98%-dominated by male performers to the point where she couldn’t get gigs she needed to become a heavy-hitter in the genre. Not only that, she had to watch women far less talented go and do what she believed she deserved after her hard work and patience. What vaulted them ahead on the food chain was the branding they carried with them as Playboy models. Audiences weren’t necessarily going for the music as much as the spectacle that label inherently brought with it. So despite being the “goody-two-shoes” everyone who knows the real Rhiannon is, she took the plunge and liberated her outlook in the process. Monk takes a peek behind the curtain at artist, manager, publicist, image-consultant, etc. Rozier wears each of those hats for the DJ Rhiannon persona herself and therefore crafted said image from the start. Her move towards Playboy wasn’t “slutty” or “opportunistic” like social media outsiders are quick to judge—it was calculated. There’s something inspiring to this fact for young women the world over. She’s showing them that it’s okay to take control of their bodies and use a handicapped system against itself to find success. Who she is on stage or online isn’t necessarily who she is in the real world. It is possible to be the person you want to be while also providing an audience what they crave. Closed-minded thinking be damned—life and art can be light years apart. B |

• The Boyfriend Game, dir. Alice Englert, 7 min. – Australia

• Concerning the Bodyguard, dir. Kasra Farahani, 10 min. – USA

It’s not surprising that Kasra Farahani‘s cinematic adaptation of Donald Barthelme‘s short satirical story Concerning the Bodyguard would attract Salman Rushdie as its narrator. Given the author’s history after publishing The Satanic Verses and having a fatwā issued by Ayatollah Khomeini calling for his death, taking part in a film that questions the disparity between a hired bodyguard and his political principal in a Middle Eastern state would be the type of thing he’d jump at the chance to participate in. There’s a chasm the world over separating those with means and those paid to protect them—one so wide you’d imagine there would be many more inside job assassinations than there are. After all, if the man tasked with saving someone’s life isn’t compensated enough to trade his own in the process, who truly has the power? Farahani brings the story to life through a series of silent vignettes of mundane activities shared by the working class and aristocratic elite in gorgeous slomotion and captivating composition. Rushdie’s narration consists of open-ended questions, queries positing whether the characters onscreen have ulterior motives or whether the man counting on their expertise would think to wonder the same. Where’s the ceiling to what someone would do for another? Does it lower or rise if that person is merely engaged in an occupation to pay bills and not involved because his politics mirror that of the party he assists? It’s almost a certainty that the patron is less than savory and definitely assured that he can’t be bothered to think about the wellbeing of anyone but himself. Money will pay for his family and money will provide him safety. It’s an intriguing tale of power and assumptions as we wait for chaos. The whole thing could be a psychological experiment, asking us whether or not the constant mention of a “new bodyguard” spells disaster in the waiting. The fact that I did places a personal spin on what’s at its core a simple list of what ifs delivered matter-of-factly and with little emotion. It’s the audience who decides the tone, our personal beliefs and historical/cultural backgrounds projecting prejudices and preconceived notions upon a banal (yet beautiful) sequence of events and quantifiable statistics factoring in. The fuse is lit and we decide whether it fizzles or ignites after the story ends. Is the bodyguard complicit, loyal, traitorous, innocuous, all or none? Is he thanked or blamed or simply forgotten? And can he forgive himself when his principal proves a monster? B |

• Dredger, dir. Phillip Barker, 17 min. – Canada

Programme 8

Premiering Monday, September 14th at 9:45pm | AGO

• The Call, dir. Zamo Mkhwanazi, 11 min. – South Africa

• Wolkaan, dir. Bahar Noorizadeh, 30 min. – Canada/Iran/USA

Writer/director Bahar Noorizadeh had this to say about her latest experimental short Wolkaan on its Kickstarter page: “As an immigrant from Iran, I am facing the slow and painful loss of language and culture from my intimate life on a daily basis. I feel a connection in this with the city of Tehran itself. Tehran is a forgetful city, always relying on the present moment and not withholding to its past. Through an apocalypse I want to give Tehran the opportunity to freeze eternally under the heavy lava erupting from the volcano. Wolkaan deals with the issue of preserving memory within a culture of diaspora. In this, the film itself becomes a space for meditation on loss and forgetting, and possibly forgiving.” I’m not sure anyone could say anything better about its goals or meaning. Without this context, though, the film is merely two stories conjoined by that apocalyptic idea of volcanic destruction. Whether an actual eruption shot in gorgeous cinematography above Tehran with the gradually moving lava crackling through empty streets below as the city uncoils in brightly lit celebration or a father (Farid Kossari) and son (Sepehr Salehi) traveling through Mid-West America ending up in an outdoor dinosaur park with its own sculpted mountain that eventually holds its own news of mortality, the work becomes more about the image than the mirrored contextual relationship between life and death. To go from such quiet reverence to the conversation of youthful curiosity is jarring and perhaps a little confusing too. Both halves living in their own present now are documented so the world can never forget. It’s quietly contemplative and resonate enough to conjure your own memories from what’s onscreen and I like that about it if not the realization it proves its depth in what you bring to the table rather than itself. Wrapping my head around that part is hard because we aren’t seeing abstraction. We’re shown actual stories that somehow prove less interesting than how we project ourselves upon them. I think that was the goal, but I can’t intrinsically trust it because my mind continues to want to understand it externally. But even if I fail at reconciling this aspect of the whole, I can’t deny the visceral appeal of simply looking at these moments of man juxtaposed with nature and the beauty in their ability to catalyze rebirth. To forget is to experience anew—progress born from extinction. C+ |

• Bunny, dir. Megha Ramaswamy, 19 min. – India

Some films end with me desperately trying to find a way to love them to no avail. Megha Ramaswamy‘s Bunny is just such a piece. It is beautifully shot with a Wes Anderson sense of whimsical artifice that’s devoid of dialogue besides the cries of a child. It’s a fantastical fable about a little girl’s (Syesha P Adnani) friend/stuffed animal, its death at the (assumed) hands of a frustrated older sister, and miraculous resurrection with the help of a neighbor boy (Faizan Mohammed). Weird, eccentric things occur every step of the way and the end ultimately arrives with a disturbing tone. I think it’s supposed to be hopeful and optimistic, but all I saw was death and despair: a toy of such importance leading its owner astray towards oblivion. This is probably due to a cultural disparity from Ramaswamy’s spiritual/Indian visual metaphors. Perhaps unexplained moments like the girl jumping to unlock her apartment’s door leading her to float in the air or the boy and the bunny walking towards a wall with an outline of the two awaiting their presence can be chalked up to traditional narratives and motifs unfamiliar to me. Marbles play a big role too—sometimes in the girl’s mouth and others signifying rebirth in their being left behind from a magical event. Ramaswamy jumps to slomo vignettes of the children painted like bunnies on a darkened, snowy night, often cross-cutting the two as they engage in similar acts at different locations for a paralleling I cannot decipher. Pieces are great—some of the most memorable imagery I’ve seen within the Toronto International Film Festival’s shorts program. So it’s impossible to discount the work completely. I loved the dirt stain representing blood soaking the boy’s hands as he tries to bring the plush rabbit to life. I loved the girl inexplicably trapped sitting on a chair affixed to a wall halfway between floor and ceiling while her sister constructs a puzzle below. The sense that this bunny is all that provides these two kids with imagination in a serious world trying to squash it is noticeable too if not overtly abstracted. Because we leave the boy in tears and the girl without a smile, though, it’s hard not to think the story culminates with a tragic end masked by its fluffy surface. C |

• The Return of Erkin, dir. Maria Guskova, 29 min. – Russia

Programme 9

Premiering Tuesday, September 15th at 10:00pm | TIFF Bell Lightbox

• The Swimming Lesson, dir. Olivia Boudreau, 11 min. – Canada

The synopsis talks about how Olivia Boudreau‘s Le cours de natation [The Swimming Lesson] shows a seven-year old girl (Jasmine Lemée) getting the opportunity to take a step forward towards independence. I find that to be more than a little misleading. This notion is included, especially considering her mother (Marilyn Castonguay) simply gives her a nudge in the locker room before leaving without a word, but does Lemée actual embrace this newfound self-sufficiency? Someone eventually collects her from the solitude of crippling fear on a poolside bench, leading her into the water for a bit of basic exercise, but a quick psychological jolt sends her into a metaphorically vast ocean all alone. The film provides Lemée the step, but she refuses to comply. Instead the result proves to be more an example of bad parenting than anything else. And while I’d say it was a success in this goal—the production is high quality and the acting true-to-life—I don’t believe it was Boudreau’s intent. Perhaps it was and the person writing the marketing blurb didn’t understand, but Boudreau still has final approval of such things, right? I don’t see a child finding strength when I watch Lemée smile at others but never engage them. I don’t notice it in her daydream of hope for the warmth she’s obviously not getting at home either. To me the film is a sad story of woe, a little girl silently crying for help and love but not receiving any. I wouldn’t be surprised if she never got back into the water again. C- |

• Latchkey Kids, dir. Elad Goldman, 22 min. – Israel

Love takes many forms and sometimes they can be confusing when you’ve never experienced a divide. For Gur (Yoav Rotman) and Daniel (Gaia Shalita Katz), growing up with absentee parents and for all intents and purposes raising each other has cultivated a deeply rooted bond. They’ve promised to never leave the other alone and they mean it. But while Daniel has matured to the point of understanding that loyalty stems from a familial place, Gur still cannot separate a sense of ownership in her love. It has crippled him to become uncomfortable with his girlfriend Osnat’s (Tamara Friedland) desire for a sexual evolution in their relationship. And it has filled him with jealous rage towards whatever boy Daniel decides to bring home. Latchkey Kids becomes a rather intriguing watch as a result of this because it’s hard to separate the concept of incest from the idea of being over-protective. Writer/director Elad Goldman takes care to never truly push it to the dark places a more twisted mind utilizing the horror genre would, but the connotation is hard to ignore. It becomes the duty of the actors to overcome this taboo with an honesty to their performances that makes their actions believable in context with the sheltered lives devoid of an adult hand to steer them they’ve led. I don’t think anything sexual would ever occur between them, but it surely could from the outside looking in like where Evyatar’s (Hillel Cappon) potential suitor to Daniel resides. Rotman and Katz are fantastic in their roles, changing from the happy calm of routine and comradery to the pained response of lies and manipulation. Gur’s world is collapsing around him as their age exceeds the constraints of where their bond has taken them. Daniel’s already has fallen—this is why she seeks the comfort of a normal romantic love to complement the platonic one shared with her brother. It’s as much a desire for joy as it is an escape from the stifling atmosphere that’s grown at home. Even so, blood is thicker than water and at a certain point she does have to choose. No matter what her head says, her heart will ultimately prevail. She may not be quite as ready to let go as she thinks. B |

• Waves ’98, dir. Ely Dagher, 15 min. – Lebanon/Qatar

Downtown Beirut is Waves ’98‘s lead character Omar’s (Elie Bassila)—a virtual, teenage stand-in for writer/director Ely Dagher—”white whale”. It’s a world he has yet to experience close-up, relegated to peering over and through concrete buildings from his safe suburban rooftop at a city split in two between the Muslim West and Christian East. Safety comes at the price of monotony and boredom, a perpetual news cycle of chaos and talk for peace that does nothing but instill fear or posit empty promises. The question becomes when enough will prove enough to finally cross the border and see what’s true himself. The answer is the allure of a glowing aura beckoning him to do so. This light is the hope and promise of a rejuvenated city, a beacon to attract young open-minded people to cut through the prejudices and segregation and find a common ground of beauty in a once-great city. Manifested as a sort of Pleasure Island within a mammoth golden elephant housing the memory of its glory and joy for those willing to remember. Is it a fantasy—some communal aspiration fragile enough to shatter into pieces once sleep is disturbed? At a certain point our avoidance of reality’s harshness or desire for more serve only as idle thoughts without action so we’ll awaken decades later to the same circumstances or worse. Beirut is calling and to answer is to do more than dream. My cousin visited Lebanon a couple years back when he was working in Saudi Arabia—the only family member of my generation (and perhaps our parents’) to do so despite distant relatives still residing in the country. The consummate tourist with camera in hand, he neglected to heed the warnings of signs demarking these religious/political/ideological borders and started snapping across their invisible lines. Someone saw and made him stop because paranoia and fear rule above the desire to share what the country has to offer to anyone willing to discover it. I couldn’t imagine being born within this quagmire like Dagher, minutes from the heart of a giant city like Beirut yet unsure of what might happen after closing that gap. Telling what in his words is an “artistic exploration of [his] current relation with Lebanon” as much as narrative via animation (with some video footage mixed in) is the perfect way to depict the crumbling ruins against the hopeful paradise this elephant that never forgets projects. The emotion of this relationship can’t help but hypothesize about an unknown that his imagination can render as a re-creation of the past now that the present seems to be moving farther away from it. As an outsider you begin to lose the intimate grasp once possessed, the truth now separated by an expanding ocean. But just as those waves threaten to pull us away, they also have the power to push us back to shore. B+ |

• The Guy From Work, dir. Jean-François Leblanc, 14 min. – Canada

• The Fantastic Love of Beeboy & Flowergirl, dir. Clemens Roth, 10 min. – Germany

In the grand picture book aesthetic of Bryan Fuller‘s Pushing Daises, Clemens Roth‘s The Fantastic Love of Beeboy & Flowergirl is a delightful little fantasy of over-the-top whimsy. Peter (Florian Prokop) is forced to live inside a bee suit due to killer bees perpetually floating around him like dirt on Peanuts‘ Pig-Pen, destined to create honey and live a life of solitude. Elsa (Elisa Schlott), a waitress who loves flowers the world over and makes them out of origami, is full of life and wonder beyond her four walls. One fateful day they meet, fall in love, and try to find a way to rid themselves of the bees to live happily ever after. Compromise isn’t changing one half for the benefit of the other, though, and like with most relationships something else must be done. Narrated by the affably soothing voice of Martin Umbach, this eccentric tale of romance is littered with flashbacks, diagrams, and carefully curated sets to describe and/or deflect from courtesy of language much rosier than what we witness onscreen. Watching as the bees simultaneously torturing and providing sustenance to Peter kill his parents earns a chuckle if only because it’s flippantly dismissed as a tiny, unfortunate detail that couldn’t be avoided. The juxtaposition of sunny disposition and dark subject matter continues towards a “Romeo and Juliet”-esque finale that brings a smile to your face despite knowing exactly what the words spoken mean. But that’s the thing about love, isn’t it? It’s messy, complicated, and worth every single concession if success can be found in their aftermath. I love the tone and the look of Roth’s work with everything placed just left of reality. After all, Peter and Elsa are seeking to leave it for the fantasyland of happiness their union seems too troublesome to find for an extended period of time. The bees appear to be animated wood block sculptures and the flowers enhanced rice paper creations glowing and moving in their folded, box-like way while the rest is left to the imagination with empty jars supposedly full of honey and newly discovered blossoms from exotic lands built at a desk without the necessity of travel. Roth’s short is infectious in its minimalist grandeur and gorgeous to behold as its bittersweet depiction of love’s sacrifices show what it ultimately means to choose it over everything else. Love quite literally conquers all. B+ |

• Peacock, dir. Ondrej Hudecek, 26 min. – Czech Republic

Programme 10

Premiering Wednesday, September 16th at 6:45pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• Quiet Zone, dir. David Bryant, Karl Lemieux, 14 min. – Canada

This is the type of experimental movie I can get behind because it doesn’t specifically hinge on form and form alone. What David Bryant and Karl Lemieux have done is distort their film with contextual purpose (not that others don’t, it’s just not merely abstract here). The over-exposed fields and darkened waves of burned celluloid trap us inside the head of Ondes et silence’s [Quiet Zone] narrators Nicols Fox and Katherine Peacock. Both women suffer from electromagnetic hypersensitivity—think Michael McKean‘s character on Better Call Saul—where the power of electromagnetic fields literally makes them ill. As Katherine states at the beginning, she believed the sound of airplanes in youth was the sun moving through the sky. And Nichols: she had to leave her house of twenty-two years once a neighbor installed wifi next-door. Their tales are descriptive, but those of us who don’t know first-hand what they’re going through on a daily basis would still be lost without Bryant and Lemieux’s aesthetic choice to visually recreate the experience. Bright yellows and reds permeate the frame until we cannot make out exactly what we’re looking at; high contrast black and white create shadowy figures amidst lost imagery outlined in the dark. Coupled with the dull drone of white noise and buzz of electronics, you feel warmer and uncomfortable. Everything in front of us slowly and imperceptibly burning from invisible radiation becomes magnified as though underneath a microscope. The danger surrounding us is suddenly unavoidable, creeping ever so close to consume. It’s so unhinged that even sprocket holes make an appearance from time to time. So while it conjures thoughts of experimental artists utilizing rotoscoping effects or treated film—as it should—Quiet Zone is literal catharsis for our empathy along with being a formal one. We not only feel something on a base level of beauty and emotion, but also towards the plight of two souls we’d be quick to dismiss as crackpots or hypochondriacs. On the contrary, this syndrome is legitimate and we all experience it on an infinitely smaller scale. Nicols and Katherine simply endure it on a level those like you and me would compare to sensory depravation torture. They live in a world where it’s impossible to escape this electromagnetic pull. Even in the titular “quiet zone” advertised as “radio silent” pulsates to make their skin crawl as yours does watching through their eyes. B+ |

• Clouds of Autumn, dir. Trevor Mack, Matthew Taylor Blais, 15 min. – Canada

• Nulla Nulla, dir. Dylan River, 6 min. – Australia

• Hide & Seek, dir. Kimie Tanaka, 22 min. – France/Japan/Singapore

There are no easy answers when it comes to psychological and emotional conditions. What a “normal” person believes to be so easy could very well prove impossible for another no matter how mundane or seemingly harmless the task might appear. Kimie Tanaka‘s short Hide & Seek depicts this struggle via a young man named Kotaro (Kuniaki Nakamura) who hasn’t left his home in over a decade. Shut-in his room except to use the bathroom, he even waits until his mother (Sachiko Matsuura‘s Mitsuko) leaves the hallway before opening the door to acquire the meal try she’s left behind. He’ll escape to the kitchen for a snack sometimes as well and it’s on one such journey that he discovers his mother unconscious on the floor. Parallel to the domestic underpinnings of this dynamic, Kotaro’s brother Shoichi (Masaki Miura) is also introduced in Tokyo where he works as a nurse. More or less going through the motions at this point, he sleepwalks through the night shift helping an elderly woman use the bathroom—lying about not hearing her from the other side of the door for the sake of keeping her dignity intact and allowing the task to be completed. Shoichi is frustrated by his family back home, especially his mother for catering to Kotaro and refusing to see a doctor because it would mean leaving him alone. So set in believing the phantom ailment his brother suffers from as unnecessarily childish, he wouldn’t think twice about committing him if push came to shove. The opportunity soon arrives and Tanaka’s message about hypocrisy and selfishness shines as a result. She carefully mirrors Shoichi’s personal and professional lives, showing how quick he’ll give a patient whatever she desires and still refuse to attempt understanding what’s troubling his brother. The woman he walks to the bathroom each night could feasibly be forced to wear a catheter yet he carries on regardless. But Kotaro—now without either parent and obviously full of fear towards the outside world—can’t merit the benefit of the doubt because it’ll be inconvenient to do so. Words are exchanged in error and we’re exposed to how broken Kotaro is and how unsympathetic Shoichi continues to be towards him. While we’re often too close to cogently measure certain situations, we hopefully acknowledge such before it’s too late. B |

• Tuesday, dir. Ziya Demirel, 12 min. – Turkey/France

• Oslo’s Rose, dir. The Sporadic Film Collective, 7 min. – Norway

• A Tale of Love, Madness and Death, dir. Mijael Bustos Gutiérrez, 22 min. – Chile

Programme 11

Premiering Wednesday, September 16th at 10:00pm | Scotiabank Theatre

• A Few Seconds, dir. Nora El Hourch, 16 min. – France

It starts with sex—violent sex. Out of context you don’t quite know the exact circumstances, but everything makes sense once you hear Zenib’s (Charlotte Bartocci) voice against starkly quiet images of the Parisian hosting center where she resides. Raped and left with a child she’s begun to love, Zenib prays he will look like her so as not to become one more remembrance of an assailant that haunts her dreams. This group of haunted souls that has become her friends helps, providing an escape from the terror even if everyone’s a bit on edge and easily pushed to explode in violent rages themselves. But for the most part they enjoy each other’s company, laughing and even going out for a night of kinetic excitement when the inspiration hits. By focusing on Zenib, Nora El Hourch‘s A Few Seconds begins as a piece of hopeful optimism—of tragedy turning to promise. Her tale is but one side of the coin, however, and the filmmaker is quick to show the second halfway through via Sam (Marie Tirmont). Unlike her ready-to-pop friend, Sam cannot see a rosy outcome nor hold onto something that could turn the horror she experienced into anything more than a waking nightmare. She’s withdrawn, trapped inside her head, and unable to break free. This is what you imagine when you hear about such heinous acts—a victim scarred, forever lost in the memory of what mankind is capable of doing, and reconciled to mistrusting everyone around her. She and Zenib have gone in opposite directions and neither can be blamed. The film’s complex with even more characters than these two to show how society and decency has failed. Just look at Jessica (Camille Lellouche) and Gloria’s (Maly Diallo) rage and frustration lashing out at one another, using their tough exteriors for punching bags when the people they’d like to get back at are nowhere to be found. Add Bonhomme’s (Charlotte-Victoire Le Grain) desire to mediate and stop the rest from going too far and you have a full-fledged community running the gamut of disparate personalities and demeanors to show how universal abuse is. It doesn’t target the weak, but a complete gender with no exception. Quite literally a few seconds can change you forever—the how is unknown. What’s certain is that the choice between life and death is much closer than you’d expect. B+ |

• BAM, dir. Howie Shia, 5 min. – Canada

While Howie Shia‘s aesthetic is accurately labeled gritty, that grit is less about being aggressive or “dirty” than it is about lending it an experimental film beauty gorgeous to behold against polished Hollywood studio fare. Just like its main character, BAM becomes a powder keg of duality with its two halves clashing to create something wholly unique and impossible to categorize. Greek Gods in giant blue form loom over the proceedings as the young boy they watch wrestles with an implicit brute force he cannot reconcile against a quiet contemplative desire to do good. It’s a struggle that makes his most selfless moments manifest as much or more fear in those witnessing his actions than when he’s at his most selfish. That rage cultivates his compassion and suppresses it in one flew swoop. A contemporary urban retelling of Hercules at its core, Shia’s grungy style conjures images of Keith Haring‘s work with a Cubist spin—especially with the larger Gods slumped and curved. The paint wipes and ink smears signifying a subway train’s speed delivers brilliant design that speaks via form and material, retaining its artifice just as its man-made rendering evolves into something beyond mere representation. We become consumed by this black and white lined world, wondering about the flourishes of blue seen floating inside and outside the central boxer moving from childhood to teen years to a career and ultimately love. The color soon proves his reservoir of immortal strength, growing as the years pass until discovering he’ll do anything for it to drain away from his soul. The epitome of the bully archetype, he’s simultaneously fearsome and frightened. Sans dialogue in lieu of music composed by his brothers Leo (hip-hop artist LEO37) and Tim instilling a sense of metallic masculinity rising in volume with anger and softening with remorse, BAM hinges on its visuals and character nuance to understand what’s on display. The cuts from instigation to eyes sharpening and fists coiling to his quick burst of violence culminating in a tragic look by those watching that screams, “He’s a monster!” perfectly encapsulate the aggression he cannot subdue. His menacing face in the ring juxtaposed with a small smile alongside his better half depicts the Jekyll and Hyde dynamic we all combat at some point in our lives. The worst fear possible is the one pointed within—that uncertainty in whether we can stop being what society deems we must despite perpetually being to our detriment. B+ |

• The Man Who Shot Hollywood, dir. Barry Avrich, 12 min. – Canada

• The Magnetic Nature, dir. Mateo Bendesky, 17 min. – Argentina

• 4 Quarters, dir. Ashley McKenzie, 13 min. – Canada

• Rate Me, dir. Fyzal Boulifa, 17 min. – UK

• Bird Hearts, dir. Halfdan Olav Ullmann Tøndel, 25 min. – Norway