From time to time, filmmakers, film critics, and film buffs will make references to a period in film history known as the French New Wave. For some people this is a term to throw out just to sound impressive, while for others it carries inspiration and significance, representing a defining moment of cinematic individuality and innovation. However, it is important to recognize that this moment in history did not happen overnight, and was in fact the culmination of many different influences from the film periods prior. For those with no knowledge of French New Wave, we’ll start this overview from the top.

French New Wave was a term often associated with a group French filmmakers of the late 1950s and 1960s, marked by their self-conscious rejection of classical cinematic form and their spirit of youthful iconoclasm. The term was first coined by journalist Françoise Giroud in his 1958 writings for the magazine L’Express, when he used the term to describe the new generation emerging at the start of the Fifth Republic, and with their sudden emergence in 1958, this group of young filmmakers were thought to embody this phenomenon in their work.

Through their immersion in French cine-clubs, they became exposed to Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema, which offered an alternative to what they saw to be a decline in French cinema. Voicing their opinions together as film critics, they rebelled against the mainstream cinematic trend, which in post-war conditions had fallen back on old traditional and heavily reliant on novellic adaptations and the notion of a “cinema of quality”.

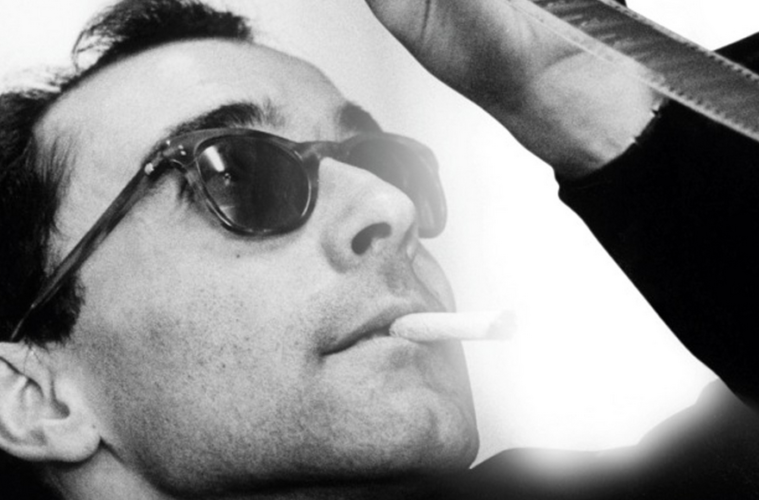

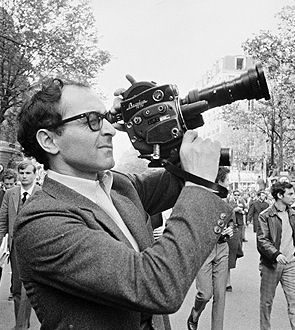

By the end of the 1950s, many of these then critics began to write and direct their own films, which often involved experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm. While many filmmakers would end up being associated with Nouvelle vague, or New Wave, a core group of film critics turned filmmakers from a single periodical, including Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Jacques Rivette, Eric Rohmer, Claude Chabrol.

Cinémathèque

From 1946 to 1958, the Fourth Republic of France (governed by the fourth republican constitution) marked a period of governmental instability during an era of post-war economic growth. In many ways, the Fourth Republic was a revival of the pre-war Third Republic, and was equally ineffective and problematic. The film industry in France mirrored this to a degree, falling back on its pre-war aesthetics in story choices, often based closely on literature, and limiting funding to only those already established within the system.

During this time, a number of film societies and ciné-clubs began, and for the first time since the end of the war, French audiences were exposed to a diverse variety of cinema outside the French studio sphere. Henri Langlois, founder and curator of the Cinémathèque Française, was one of the father figures of the movement, known for screening and collecting historical films. Langlois was a cinephile and film archivist, who worked the preserve films and film history in the post-war era. Langlois began collecting films in the 1930s, and had accumulated one of the world’s largest collections by the outbreak of World War II. At the threat of having his collection destroyed by the German authorities, he smuggled huge numbers of films to unoccupied areas of France for protection.

Following the war, Langlois was able to attain a subsidy from the French government for the collection, as well as a small screening room to show the films. During this time, the audience for mainstream cinema was in decline, but cinema culture was maintained through these ciné-clubs and art houses, which focused on retrospective and noncommercial cinema.

Two ciné-clubs regularly patronized by future filmmakers of nouvelle vague were the “Ciné-club du Quartier Latin,” and “Objectif 49.” “Ciné-club du Quartier Latin,” (translates to Cinema Club of the Latin Quarter) specialized in American films, and was frequented by Jacques Rivette. “Objectif 49” organized by cinephiles like André Bazin, Jacques Doniol-Valcroze, and Alexandre Astruc, as well sponsorship from Robert Bresson and Jean Cocteau, showed its members new, unreleased films.

“Objectif 49” founder Jean-Geores Auriol also founded the only serious film magazine in France at the time, Revue du cinema. When the magazine collapsed around the time of Auriol’s accidental death in 1950, a void was created in French criticism that Bazin and his contemporaries hoped to fill. When Bazin finally did establish his own periodical, Cahiers du cinema, it was in these ciné-clubs that he met many of the young cinephiles he would recruit as writers.

Later in his career, then filmmaker François Truffaut would open his film Stolen Kisses (1968), part of his Antione Doniel cycle, with a shot of the then closed up Cinémathèque, dedicating the film to Langlois, reflecting back on this period in his life.

Cahiers du cinema

André Bazin, alongside Jacques Doniol-Valcroze and Lo Duca, founded the film magazine Cahiers du cinema in 1951. Bazin championed films that depicted what he referred to as an “objective reality” that didn’t mask the hardships and harsh realities of everyday life, such as in Italian neorealist films and documentaries. He also firmly supported the notion that films should be personalized by the director, each one representing the director’s personal vision.

At the time of the Cahiers formation, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, and Jacques Rivette were writing for their own journal, Gazette du cinema, (which had been created after the demise of Revue du cinema) and thus became some of the first Cahiers writers. Also at the time of magazine’s foundation Rivette had already begun making his first short films. This is an important thought to keep in mind, as many of the writers who wrote for Cahiers envisioned themselves making their own films at some point.

It is important to recognize that while the Cahiers critics shared some viewed, there was diversity among the group, ranging both in age, as well as cinematic aesthetics. It was through this diverse thinking that they were able to have engaged debates, and challenged each others’ views.

Many of the writers for Cahiers were frequent attendees of Cinémathèque Française, and would often write about it in their magazine, regarding it as their version of a film school. Truffaut was one of these individuals, who had met Bazin many years earlier through a film society. In 1950, Truffaut had enlisted in the army, gone AWOL, and ended up in a military prison. It was Bazin who had helped him get released and discharged from the army, and at the time he began writing for Cahiers, Truffaut had been living with Bazin and his wife, as Bazin became the paternal mentor teenage Truffaut had long been lacking.

During this time, among the films shown at the Cinémathèque Française were Italian Neorealism films, as well as classical Hollywood films. Italian Neorealism refers to a period in Italian film where stories were set against the poor and working class in post-World War II Italy. The style was further defined and supported by critics of the Italian periodical Cinema, who had tired of the poor quality mainstream films of the time. Cahiers writers were drawn to these films for their realist depicts of post-war economic and moral conditions, as well as the stylistic choices of filming on location, often using non-professional actors.

Classical Hollywood cinema refers to the period of American film prior to the 1970s. Stylistically, it was an “invisible” style, where continuity could provide a sense of seamlessness without drawing attention to the camera. The term also applies to the mode of production at the time, meaning the Hollywood studio system. In this system, all film workers were employees of a specific studio, giving each studio its own sense of style, diminishing the individual styles of the directors. However, those directors who were able to rebel against these restrictions, infusing films with their own unique style and aesthetic (such as Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, and John Ford), did not go unnoticed by the Cahiers critics. They applauded the films of these directors, as they began to explore the notion of authorship in relation to directors.

In a conversation with a number of Cahiers writers, Howard Hawks describe his experience with his first sound film, Dawn Patrol: “I myself wrote almost the entire scenario, and during the shooting, everyone kept telling me, ‘It’s not good dialogue, it’s not dramatic. Everything is flat. Everything you’re doing is going to be flat.’ No one liked the film because none of the characters cried or screamed. When the editing was finished, the studio had so little confidence in the movie, they dispensed with the premiere. They preferred to release it discreetly, and then it turned out to be the best film of the year, and then they got in the habit of screening it for other directors and saying, ‘That’s what good dialogue is like.'”

The group also rebelled against the notion of French “cinema of quality” or “tradition of quality”. At the time, high-budget literary period films were the mainstream trend, and were highly regarded at French film festivals. They also recognized French filmmakers who shared their ideals such as Jean Renoir and Jean Vigo.

In May of 1957, after years of publicly criticizing the majority of French cinema, a number of Cahiers critics gathered around a tape recorder to discuss the current state of film in France. With what Bazin described as the most radical and decided opinions, Rivette began the discussion by stating:

I think that French cinema at the moment is unwittingly another version of British cinema, or to put it another way, it’s British cinema not recognized as such, because it’s the work of people who are none the less talented. But the films seem no more ambitious and of no more real value tha what is exemplified in British cinema… British cinema is a genre cinema, but one where the genres have no genuine roots… It’s a cinema that limps along, caught between two stools, a cinema based on supply and demand, and on the false notions on supply and demand at that. They believe that that’s the kind of thing the public wants and so that’s what they get, but in trying to play by all the rules of that game they do it badly, without either honesty or talent.

While this commentary denounces British genre films, it is important to note that Rivette was a fan of American genre directors from the 40s and 50s, such as Howard Hawks, John Ford, Nicholas Ray, and Robert Aldrich. He despised cinema that felt mass produced, and praised that which demonstrated personal vision.

It was in this same conversation that the critics discussed the important of a national cinema, and the need to create films that would attain international distribution. Rohmer this topic by declaring, “it’s precisely its universal character that gives American cinema its value. American cinema gives a lead. What should be deplored is not so much that French cinema isn’t producing worthwhile work, but that its work is shut off- I mean it doesn’t influence the work in other countries. There is no French school, at least not any more, while there is an American school and an Italian school.” He then continued this thought in saying, “French cinema doesn’t depict French society, while American cinema, like Italian cinema, is able to raise society to a level of aesthetic dignity. Perhaps in conclusion we could try to find out, if not why, at any rate in what way French cinema fails to represent contemporary France.”

When French films did emerge that seemed to break from the mainstream, the Cahiers tried to bring as much attention to it as possible. When Alain Resnais, a filmmaker who would become associated with nouvelle vague, directed a film titled Hiroshima, Mon Amour (sometimes written as Hiroshima, Notre Amour) in 1959, the Cahiers applauded this film, finding it fresh and original. The film, which explored the subject of memory, utilized an innovative use of flashbacks, providing a style with a definite break with classical cinema, reflecting a changing modern mentality in cinematic history.

When French films did emerge that seemed to break from the mainstream, the Cahiers tried to bring as much attention to it as possible. When Alain Resnais, a filmmaker who would become associated with nouvelle vague, directed a film titled Hiroshima, Mon Amour (sometimes written as Hiroshima, Notre Amour) in 1959, the Cahiers applauded this film, finding it fresh and original. The film, which explored the subject of memory, utilized an innovative use of flashbacks, providing a style with a definite break with classical cinema, reflecting a changing modern mentality in cinematic history.

As Godard described, “the very first thing that strikes you about this film is that it is totally devoid of any cinematic references. You can describe Hiroshima as Faulkner plus Stravinsky, but you can’t identify it as such and such a filmmaker plus such and such another.”

One element of Resnais’s film that did cause some interesting debate was his collaboration with screenwriter Magueritte Duras. Duras was primarily a novelist, to which the critics believe could have posed a threat to the film becoming too “literary”, but the actual film was uniquely cinematic, which the Cahiers attributed to Resnais’s talent as an auteur, and his ability to craft mise en scène and montage. It was soon after this time that a number of the critics began filming their own features, hoping to infuse these new stylistic elements into their work.

“La politique des auteurs” (the policy of authors)

Growing weary of French mainstream cinema of the time, Truffaut wrote an article titled “Une certaine tendance du cinéma français” (A Certain Tendency of French Cinema) in 1954. This article was a reaction against “Tradition of Quality” cinema in France, a term that had be coined by Jean-Pierre Barrot in the magazine L’Ecran Français the year prior. Truffaut believed that this “Tradition of Quality” not only reduced the literary heritage of France, but it also simplified cinema to the point that it was limited as an art form. Specifically, he attacks writers Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost as examples of screenwriters safely adapting and not willing to push the cinematic medium:

In truth, Aurenche and Bost work like all the scenarists in the world, like pre-war Spaak and Natanson. To their way of thinking, every story includes characters A, B, C, and D. In the interior of that equation, everything is organized in function of criteria known to them alone. The sun rises and sets like clockwork, characters disappear, others are invented, the script deviates little by little from the original and becomes a whole, formless but brilliant: a new film, step by step makes its solemn entrance into the “Tradition of Quality.”… They will tell me, “Let us admit that Aurenche and Bost are unfaithful, but do you also deny the existence of their talent…?” Talent, to be sure, is not a function of fidelity, but I consider an adaptation of value only when written by a man of the cinema. Aurenche and Bost are essentially literary men and I reproach them here for being contemptuous of the cinema by under-estimating it.

Bazin and the Cahiers critics began referring to this idea as la politique des auteurs (the policy of authors), as it became an informal manifesto of the New Wave. Later translated by Andrew Sarris, this term was renamed Auteur Theory in 1962. Auteur theory states that the director is the “author”of his films, with a personal signature visible in each. This is a shift from the previous mentality, where the artistic focus was placed on the screenwriter.

Another key element of Auteur theory came from Alexandre Astruc (notable French film critic and former member of “Objectif 49”) who discuss the notion of the caméra-stylo (camera-pen) meaning that directors should wield their cameras like writers use their pens, putting the art of storytelling in their own hands. Within the commercial apparatus of filmmaking, filmmakers should wield their camera-pens to imprint their personal impression on the film. The Cahiers writers praised the directors who worked in pursuit of this goal.

In 1956, Truffaut and Rivette interviewed Howard Hawks. Within the conversation, the Cahiers critics asked if Hawks edited his own films, to which he responded: “Oh yes! Simultaneously with the shooting, if possible. When I started out in this profession, the producers were all afraid that I made a film too short because I didn’t give them enough film for editing. And I said: ‘I don’t want you to make the movie in the cutting room, I want to make it myself on the set, and if that doesn’t suit you, too bad.’… The difficult work is the preparation: finding the story, deciding how to tell it, what to show and what not to show… I never follow a script literally and I don’t hesitate to change a script completely if I see a chance to do something interesting.”

The group also began to establish their own visual aesthetic. Mimicking their films of preference, this included a preference for a long shot for a scene as opposed to over-editing with constant cuts.

In 1958, Claude Chabrol released his film Le Beau Serge, a Hitchcock-influenced drama, which became known as the first film of the nouvelle vague, and was met with critical success.

However, a number of the other Cahiers directors also had films in the works at this point, and it would be with the feature debuts of Truffaut and Godard that the movement would gain attention and momentum.

Nouvelle Vague

At the time the Cahiers critics began experimenting with their own films, there were institutional and technical changes that impacted the movement. Following the war, the Centre National de la Cinématographie was founded in 1946, with the intention of regenerating French cinema through financing and distribution. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, much of this funding was allocated to French mainstream cinema with established directors and producers. However, when the market for mainstream cinema began to decline more funds began to be allocated smaller productions, as well as awards for completed films.

In 1957, Truffaut made a short film called Les Mistons, in which a group of young boys spy on a young woman, annoying her and her boyfriend. After its completion, Truffaut receive a financial reward, which he reinvested in his next project, which would be his first feature.

In 1953, Morris Engel and his wife wrote and directed the film Little Fugitive which told the story of a young child spending the day alone at Coney Island. Filmed on location, the film utilized a spontaneous production style, in which a concealed strap-on camera allowed the filmmakers to record without the knowledge of surrounding pedestrians. This was very influential to Truffaut, who was busy formulating his first feature-length film, The 400 Blows.

The day after shooting commenced on the film, Bazin died of leukemia at age 40. This had a deep, emotional impact on Truffaut, who had viewed Bazin as a father-figure, and so he ended up dedicating the film in Bazin’s memory.

While some of the film is based on his own life, Truffaut also borrowed moments from a few of his favorite films. There is one scene in which a line of schoolboys goes jogging through Paris. One by one, the boys sneak away from the group to go play elsewhere in the city. This scene in practically a shot-by-shot homage to a scene in Jean Vigo’s 1933 film Zéro de conduite, which drew on the director’s childhood boarding school experiences.

In an article on first person plural, Cahiers critic Fereydoun Hoveyda applauded the film, saying:

Unafraid to mix genres, Truffaut begins in the usual narrative vein, then, without warning, moves into reportage, goes back to what appears to be the story and on to a portrait of manners, with a bit of comedy and tragedy inserted here and there. He tells us a complete story just as it should be told, makes his presence felt as a scrupulous observer of reality, turns investigator, then poet, and completes his film on a very beautiful image which is also a first-rate director’s idea.

The 400 Blows went on to win the Grand Prix at the Cannes Film Festival that year, which was the festivals second-most prestigious award at the time. This win is humorous in the sense that Truffaut had been the one critic banned from the Festival one-year prior.

In 1958, Godard and Truffaut had attended Expo 58, the first major world’s fair after World War II, located in Brussels. There, the two critics viewed and applauded Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil. After seeing this film, Godard felt it was time to make his first feature film.

Co-written with Truffaut, Breathless featured actors Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg and offered a bold visual style and innovative techniques. Between breaking the eye-line match rule, he also utilized the use of jump cuts, both of which are violate classical continuity editing, which ends up being a way of breaking down the appearance of continuous time and space. One example of his use of jump cut is when the two main characters are riding around in a convertible. In one shot, Jean Seberg is sitting in the passenger seat with her hands on her legs, and then in the next cut she is shown from the same angle but now holding a mirror. There is an abrupt feeling of lost time, which moves away from the classical sense of seamlessness.

It is important to note that Godard was not the first filmmaker to make use of the jump cut. George Méliès frequently used jump cuts as a way of simulating magic tricks, having something be absent in one frame, and then present in the next. However, Godard was the first contemporary filmmaker to utilize this technique in a narrative film, working against what he saw as the flawed classical style of then French cinema.

Breathless also contains a number of cinematic references, as Godard calls attention to the medium he loves. In his portrayal of Michel, Belmondo does his best to imitate Humphrey Bogart’s constant lip-rubbing, and then takes notice of a photo of Bogart outside a movie theater. Later in the film, Michel and Patricia attend a screening of the film Westbound, once again drawing attention to films within the film. Godard even pays tribute to Cahiers, as Michel passes by a woman selling copies of the publication on the street. She asks him, “Monsieur, do you support youth?” He refuses, saying “No, I prefer the old.”

As Godard and Truffaut progressed in the filmmaking careers, they’re styles became more differing from each other. Truffaut maintained more of a classical style working with scripts, while Godard somewhat abandoned scripts, giving lines to his actors on scraps of paper. In this sense, Godard had more in common with Rivette, who was also very experimental in his filmmaking.

In June of 1963, Eric Rohmer saw his position at Cahiers eliminated by his contemporaries, as the magazine began to move in a less-conservative, radical left-wing direction, against his desires to avoid overt politics.

At this point, he began focusing his full energy on his filmmaking. He would later reflect on this time, saying, “I decided I would go on filming, no matter what, and instead of looking for a subject that might be attractive to the public or a producer, I decided I would find a subject that I liked and that a producer would refuse.”

What would follow would be a series of films he deemed as his Six Moral Tales (Contes moraux). When examining these works, it’s important to recognize that Rohmer isn’t using the English definition of “moral” which would refer to distinction and identification of right and wrong. He instead draws upon the French definition of the moraliste. In his own words, he described this as, “a moraliste is someone who is interested in the description of what goes on inside man. He’s concerned with states of mind and feelings.” He then continued on to explain that the Moral Tales are about “people who like to bring their motives, the reasons for their actions, into the open, they try to analyze, they are mot people who act without thinking about what they are doing. What matters is what they think about their behavior, rather than the behavior itself.”

The first two of these tales were short films (the final four were feature length), and featured voice over narration from the main male protagonist. In The Girl at the Moceau Bakery from 1963, the character is attracted to one girl, but when she disappears, he begins courting another. While there is little conversation between the characters, the tension of the story is driven from hearing the man’s inner thoughts. The second tale, Suzanne’s Career, from the same year, involves the main character’s inner thoughts as he obsesses over the girlfriend of his friend. As an interesting nod to American cinema, the trio attends a screening of Lawrence of Arabia. Innovative at the time, these films help to set in motion what has become an accepted trend of having a protagonist’s internal monologue serve as narration.

After these early films, many of the Cahiers critics turned filmmakers were able to enjoy long careers as directors. Godard after a number of successful films, was able to explore a number of gangster film conventions in his 1964 film Band of Outsiders (Bande à part). Staring his then wife and muse Anna Karina, the film follows two men who fall in love with the same woman, and then plan a heist that goes horribly wrong.

It’s important to note that while the Cahiers filmmakers played an essentially role in nouvelle vague, they were not the only directors associated with the movement, as there were a number of other small sub-groups. One of which was referred to as the “Left Bank” group, which was a contradistinction to the “Right Bank” group that the Cahiers were part of. Aside from the physical difference of being located on opposite sides of the river, the groups also had differing perspectives in the late 1950s, as the “Left Bank” directors, including Resnais, Agnes Varda, and Jacques Demy, held a more left-wing political stance and were associated with the nouveau roman movement. This distinction blurred over time, as the Cahiers group developed a stronger political opinion in the mid-1960s.

Followers/Impact on History

While many of the Nouvelle Vague filmmakers enjoyed long careers that evolved over time, their work as writers in the 1950s and filmmakers in the 1960s has had a lasting impact on the history of cinema, and their mark can still be seen in the work of filmmakers today.

As previously mentioned, Andrew Sarris translated and evolved Truffaut’s “Une certaine tendance du cinéma français” into what is now referred to as the auteur theory in 1962. This notion of authorship is still used when discussing filmmakers within the context of film theory.

Many years after the original article, Richard Dyer summed up the importance behind Truffaut’s proclaimation, which he described as film studies’ greatest hit:

[Auteur theory] made the case for taking film seriously by seeking to show that a film could be just as profound, beautiful or important as any other kind of art, provided, following a dominant model of value in art, it was demonstrably the work of a highly individual artist. Especially audacious in this argument was the move to identify such artistry in Hollywood, which figured as the last word in non-individualized creativity (in other words, non-art) in wider cultural discourses in the period. The power of auteurism resided in its ability to mobilise a familiar argument about artistic worth and, importantly, to show that this could be used to discriminate between films. Thus, at a stroke, it both proclaimed that film could be an art (with all the cultural capital that this implies) and that there could be a form of criticism – indeed, study –of it.

French New Wave made films in many different genres often abandoning normal narrative conventions. Utilizing of real locations, improvised scripts, natural lighting and hand held cameras, they created a look that was distinctive, formulating their own sense of realism. One example of this style is in A Bout de Souffle (Breathless), where there is a scene in which Jean Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg walk down a street as Seberg sells copies of the New York Herald Tribune. This scene was filmed using a concealed camera, with common pedestrian walking into frame and interacting with the characters. The innovative ways of cutting production costs added a spontaneous feel to the film, as well as the increase sense of realism.

French New Wave made films in many different genres often abandoning normal narrative conventions. Utilizing of real locations, improvised scripts, natural lighting and hand held cameras, they created a look that was distinctive, formulating their own sense of realism. One example of this style is in A Bout de Souffle (Breathless), where there is a scene in which Jean Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg walk down a street as Seberg sells copies of the New York Herald Tribune. This scene was filmed using a concealed camera, with common pedestrian walking into frame and interacting with the characters. The innovative ways of cutting production costs added a spontaneous feel to the film, as well as the increase sense of realism.

One of the things the New Wave directors wanted to do was to draw attention to film as a medium, reminding their audience they were watching a film. One way in which they accomplished this was to have a character address the audience directly, breaking what is known as the “fourth wall.” While this technique was new and surprising at the time, it is one that occurs often in modern cinema. In the film Spaceballs from 1987, the villain Dark Helmet gets a copy of the movie Spaceballs on video and fast-forwards in order to find out where the heroes are headed. Instead of being able to fast-forward, he gets stuck on the moment he’s in and does a turn-away-then-turn back maneuver as he watches himself. In the film Ferris Beuller’s Day Off, the lead character not only addresses the audience periodically throughout the film, but at the end of the credits, questions as to why they’re still watching since the story is clearly over. Today’s audiences are comfortable with these breaks in narrative reality, but their existence is really credited to Nouvelle Vague.

French New Wave as lives on in the referential work of many modern filmmakers such as Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, and Quentin Tarantino. Scorsese and Coppola, both who rose to fame in the 1970s, which is sometimes referred to as the American new wave, have mentioned the influence these French filmmakers had on their artistic and production style. In fact, it was Truffaut himself who first recommended that Warren Beatty check out the script for Bonnie and Clyde, which would become one of the first film of the American New Wave, also know as the “New Hollywood” era of the 1970s, marking a shift in expectations in American cinema.

Perhaps the most notorious fan of French New Wave is Quentin Tarantino. In 1992, Quentin Tarantino dedicated his first feature Reservoir Dogs to Jean-Luc Godard. He later, along with Lawrence Bender, named his production company A Band Apart, which is a play on words of the French title of Band of Outsiders, which is Bande à part, a film he has often cited as one of his favorites. This film also inspired a dance scene in Tarantino’s 1994 film Pulp Fiction, in which the characters break into a dance within a restaurant.

Additionally, just as Godard and the other New Wave filmmakers did, Tarantino often references other films he admires in his own work. His most recent film, Inglourious Basterds, contained film references from films ranging from spaghetti westerns to Nazi propaganda, interlaced with carefully placed film posters and character names, forming a hyper-reality paying homage to cinema.

Just as the young writers of Cahiers were influenced by the Italian and American films of the post-war era, their own writings and productions have had an influence on the generations that have followed since. The group of young eager critics that would sit around a recording device and debate the future of cinema became one of the pivotal forces that shaped the medium they loved so dearly. As they continue to be referenced as a hallmark of film, it’s important to remember how this movement developed, and that even the greatest influencers in any moment of history had they own set of influences and driving factors. Pay attention to the fresh minds and faces that surface in this contemporary cinematic landscape; change happens when you least expect, and you never know when the next new wave will begin.

Note — most of the quotations used can be found in: Hiller, Jim ed., Cahiers du Cinema: The 1950s: Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, 1985.