After shocking and disgusting audiences at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, Leaving Neverland aired in two parts on HBO earlier this month. Wade Robson and James Safechuck’s damning accusations of years-long sexual abuse by Michael Jackson became one of the most successful documentary premieres in the network’s history.

Directed by Dan Reed, known for helming the documentaries The Paedophile Hunter and Three Days of Terror: The Charlie Hebdo Attacks, Leaving Neverland is told exclusively through people who had a direct role in the story because he believes that gives his documentaries a “real power.” He reiterates this documentary is about Wade and James, not the superstar. All footage and comments from the Jackson estate come from archive footage.

In our interview with Reed we discuss what Leaving Neverland did to his psyche, the process of turning hours of first-person interviews into a complete narrative, the overwhelming negative response from Jackson fans to the documentary, and if he plans on making another documentary about the singer’s 2005 trial.

The Film Stage: You’ve spent hundreds of hours hearing Wade Robson and James Safechuck’s stories and sorting through footage of Michael Jackson. Who would you say Michael Jackson is beyond his celebrity?

Dan Reed: That’s an interesting question. You probably heard my stock answer that I preface this with, which is this isn’t a film about Michael Jackson–it’s about Wade and James. But the question you ask is an interesting one. I might be the wrong person to answer it because my knowledge of Jackson’s biography is so restricted and my interest in his music and in his career was pretty much non-existent before I began the three-year journey of this film.

I can see that in relation to his fondness for little boys, my feeling is that he didn’t believe he was doing anything wrong. When he said, “I love little children and I would never harm them,” I suspect that he believed he was telling the truth. In common with many pedophiles out there, he believed that pedophilia is a valid sexual orientation and that the world simply doesn’t understand that and they haven’t caught up with it yet. I don’t know. That’s speculation of course, because he never discussed the subject in public, perhaps never articulated it himself. There were so many people around him enabling him and very rarely challenging him that he found it very easy to sneak in little boys, so maybe he thought he had a God-given right to do so. I think the weight of celebrity crushed his judgment, distorted his personality. He was certainly a victim of his own celebrity in many ways, but he was so ruthless and manipulative when it came to abusing little children and grooming their families that I can’t really exonerate him.

What do you think it’s done to your psyche, having spent three years on this project?

[Laughs.] I think my psyche has a pretty good workout the last thirty years, exploring war zones and crime and terrorism, and being confronted with the worst of human behavior, and also the best, but I’ve seen a lot of unpleasant things. There’s probably quite a few scars on the old psyche, but I’ve learned to compartmentalize the bad things. I keep my distance from that.

I haven’t seen any signs of psychological damage or some kind of post-traumatic symptoms. I’ve had that in the past, I think, when confronted with a lot of violence over a long period of time. But in this case, I got a lot of support from Wade and James and from working with their families. Making the film, we had the chance to do a really good thing which is to create a reference point that people can use to talk about childhood seuxal abuse. Make people aware of how it goes down, that it’s not like a violent rape and seduction. I think the psychological attrition was mitigated by the fact I thought we were essentially doing a good thing and the excitement of doing a good thing. I guess I’m pretty sort of hardened as well. To be honest, I never know how to answer that question.

Some common threads in your work are terrorism and sex crimes, but then you have a Biblical story and a few episodes of Waking the Dead. What draws you to a subject?

I think the work that I’m the most legitimately associated with and had the most creative input is my documentary work. And it’s always about revealing hidden sides, hidden complexities behind stories we think we’re familiar with from the news media. Take for example, the terrorist attack in Nairobi or Mumbai: you think you know what happened, but when you start to unravel behind the scenes of what happened and try to understand the complex way in which people have reacted, or a city or an institution have reacted. I like to deal with complexities. I like to also show that people’s reactions to these traumatic events can be very complex. All of my stories are told in a very intimate, personal register. When I tell a story about a violent incident, it’s not an expert or a journalist who comes up and tells the story. It’s pretty much exclusively the people who were there or had a direct role, and who are protagonists and participants. I think psychologically that’s a redeeming thing. There’s a certain power in a whole cast of people who were involved in a traumatic event, deciding to sit down and speak about it in a very open, vulnerable way, I think that has a real power. It becomes a collective act when I collect them all together. So that’s been a very important thing to me. Telling the inside of these big stories, using very personal accounts. It’s a mode of storytelling I specialize in and have developed. I think that’s what you see in Leaving Neverland, the techniques that I’ve used in Three Days of Terror: The Charlie Hebdo Attacks–everything from the camera angles, the lighting, the manner in which I interview people. That has all been incredibly useful in Leaving Neverland. You see the same techniques being repurposed from one subject matter to another.

Was there ever a cut of Leaving Neverland that was longer than four hours?

The longest cut we had was under five, and that was the first cut we sent to HBO. That was still at the point when we only had the families in the cut. I shot interviews with LAPD and Santa Barbara Sheriff’s Department who investigated. I had a great interview with the main prosecutor, the deputy DA from the 2005 trial. We hadn’t put those in because I had a strong feeling it needed to remain a claustrophobic story about two families. This was unseen and unheard and the first time Michael’s victims had really spoken out in any detail to the press about what happened. I thought that was an extraordinary new thing we have, and the other extraordinary thing we have is this sort of 360-degree insight into the family’s ordeal once the information about the abuse was disclosed. It becomes a drama. That’s why I think the last half hour is so powerful. It becomes a drama about relationships and a family that have been woven together over the last three-and-a-half hours. Everything kind of lands in that last half-hour of drama, which consequences in Wade’s life are a bomb exploding in the family. 4 and 3/4 hours felt like a complete story and HBO agreed, and then it became a case of what do we take out and get it down to four hours, because we were all in agreement it shouldn’t be longer than four hours.

Is there a type of child or family that Michael would choose, or did you notice that either Wade or James’ economics had anything to do with their vulnerability?

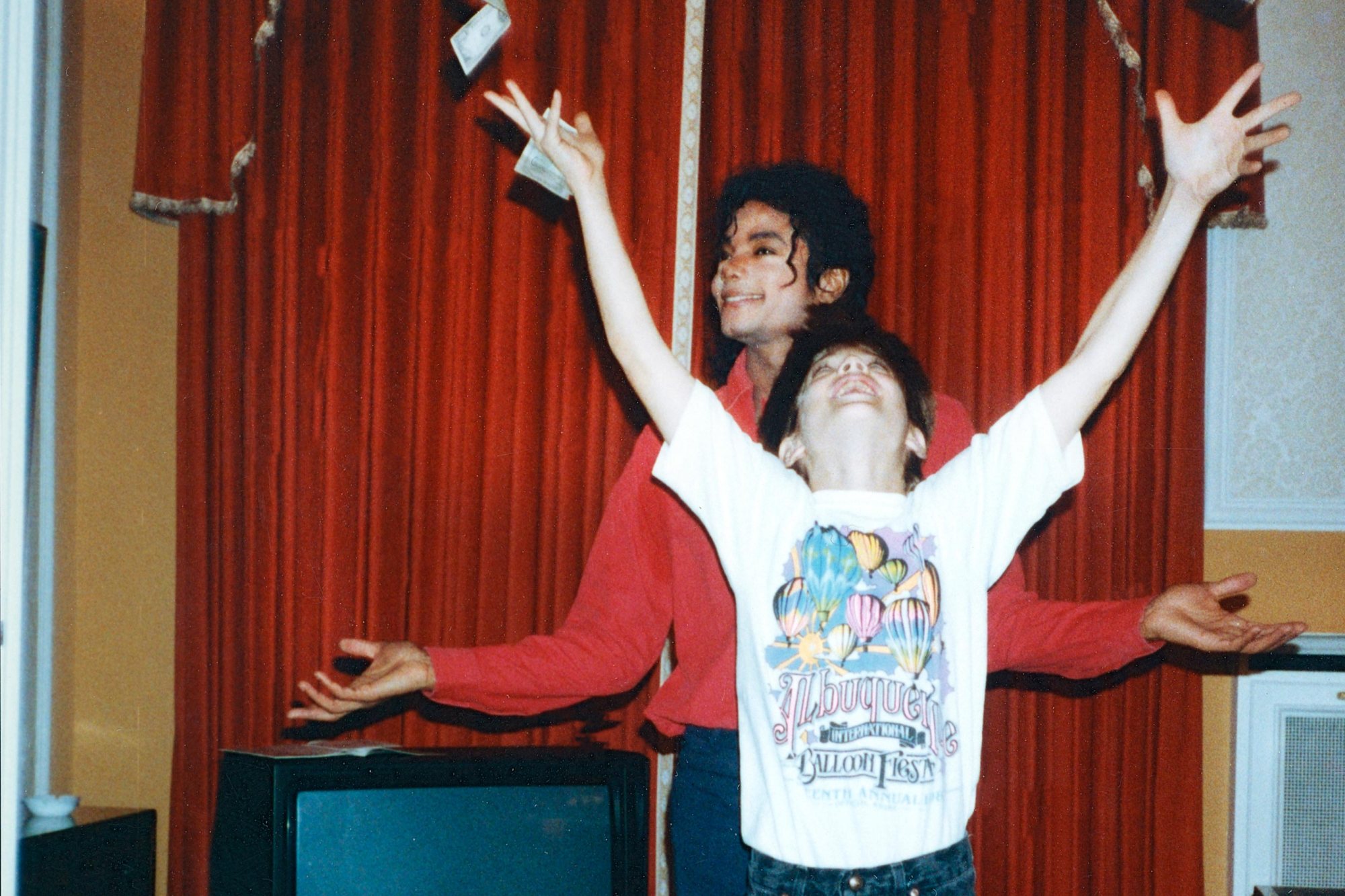

There were patterns. Typically the grooming pedophile picks families that are in some way vulnerable, and the child is a bit isolated, and when mom and dad aren’t a solid family unit. That doesn’t mean to say that pedophiles never pick on well-adjusted families, but in this case, the families that allowed their children to get close to him were often families where mom and dad are having problems and maybe the mother was drawn to Michael’s charisma, his wealth, fame, and saw proximity to Michael as an opportunity for herself and particularly for her child. So these were not wealthy families in their case. Wade’s dad was grocer and mom worked in a department store. James’s father had taken over the family business and his mom worked in a hair salon, so these were relatively modest people. You can see in the drone shots of their house that they lived modestly, not some kind of glacial, suburban residence. Just an ordinary house on an ordinary street in an ordinary American suburb. He picked on these two ordinary families. I think the characteristics the little boys always had is they are incredibly good-looking. Very, very pretty little boys. Not always the same type, but he seemed to go for the same type for a little while and then change types. James and Wade are a fairly similar type. But they are strikingly good-looking children. So those patterns are all there, and as you can see in James and Wade’s narrative they are strikingly similar. They both married very strong women and that has helped them immensely.

What is your response to the overwhelming negative feedback from die-hard Michael Jackson fans?

Well, I’m astonished that people’s first response to “I was raped as a child” is “Well, you must be lying” or “You must be out to extort money from Michael Jackson’s estate.” I think that’s kind of an astonishing and bizarre response. I wonder if they were conditioned by decades of Jackson’s propaganda. So these people don’t even seem to think independently for five seconds because if they did so they would realize what they were saying makes no sense at all. Even with the mere dusting of common sense those ideas fall apart. Just because you sue doesn’t mean you automatically win, you have to go to court. Anyone who has even watched TV knows that you don’t get money simply by suing. So I don’t know where these people spend their lives, but they have an astonishing ability to ignore reality and common sense.

They say that Wade is an admitted liar. That doesn’t make any sense either because when was he lying? They have to decide was he lying in court in 2005 or is he lying now? Presumably they mean he’s lying now. He’s the one admitting to lying in court. Presumably what the Jackson fans are saying is that he told the truth in court and that’s why he’s not a perjurer, right? Because what Wade said in court is that Michael never touched him. If that isn’t true, then he’s not a perjurer and not an admitted liar. He’s the one who said that he lied. They should be saying that he’s a man who told the truth in court.

The astonishing thing is also when you go online on Twitter and stuff, which I try not to do too much, there’s people who spend a great deal of time and care into creating videos exposing the lies of Leaving Neverland, and pretty much everything they are saying have been contradicted by the documentary itself. All you need to do is watch the documentary. There’s this thing around of “Oh, well how come Stephanie knew about the abuse, how come she was dancing when Michael Jackson died when James told her about the abuse in 2013?” Well, that’s not the case. James told his mother about the abuse in 2005, and that’s clear in the film. He told her “Michael abused me” in 2005. If you watched the film with both eyes and ears open, that’s incredibly obvious and plain. That’s the bizarre thing; they don’t even seem to watch the film. A lot of what they’re saying is based on the letter the Jackson estate’s lawyer wrote before he watched the film. So it’s not a dialogue between the Jackson truthers and my documentary, it’s an internal dialogue within the community of Jackson truthers kind of convincing one another that “we gotcha!” when in fact, none of it relates to my documentary. It’s like people shouting inside some kind of cult temple and none of them ever look outside.

How does it feel to have you and your work under this scrutiny?

I feel pretty comfortable because I subjected James and Wade’s accounts to such scrutiny before we even began editing. We fact-checked and re-fact checked and re-fact checked and scrutinized. I feel pretty comfortable with the amount of preparation we did and therefore I don’t think there’s anything anyone can say that cast any real doubt on it. I’m very comfortable with my work being scrutinized as much as it is and I welcome the scrutiny because a story shouldn’t be accepted at face value, anything anyone can say to challenge a story should. Most of the challenges that have come from the Jackson fan community are not valid. They are based on false information. Personally, how do I feel about it? I feel great about having my work scrutinized. I pride myself on my reputation for good journalism and complex stories and great details but never deviating from the highest journalistic standards. I feel quite satisfied.

Was it intentional to have James and Wade not be emotional in the film? They never became too emotional. There’s maybe one or two moments where Wade cries, but it’s very subtle, they’re not showing a lot of emotion.

No, there was no intent. I mean, Wade does cry rather a lot, I thought. Maybe I’m being a stoic Englishman, but he does shed quite a lot of tears for my taste. I think it’s fine that he’s emotional. James is not at all emotional. You can see how perturbed he is and how upset he is within himself but he doesn’t let that emotion surface. I thought Wade showed a lot of emotion but James sort of held in. He didn’t want to break down. That’s a criticism that is thrown at these young men, like, “Why are you not more upset when you talk about this stuff?” I think that displays the ignorance of how people actually process the kind of long term psychological impacts of child sexual abuse. Remember, neither of these guys are saying Michael pushed me down or threw me in a corner and violently raped me. That’s not what they’re saying. But what’s the way most people imagine child sexual abuse.

The damage and the pain of the abuse is much more subtle than that. For them the sexual abuse at the time was not traumatic. They say it in the film that it was pleasurable, a loving, gentle, caring experience. Child sexual abuse is a criminal act, we know that. It’s not like they are remembering something that really upset them at the time. The psychological consequences play out during adulthood because your life is built on a lie, your childhood is built on a lie. You have to lie to everyone: your mother, your father, your sister, your brother. And that takes a toll. This is not somebody remembering being raped or someone attempting to murder them or someone killing someone close to them. It’s not that kind of trauma. People have to take that on board. People still don’t understand, even when they watch my film they still haven’t fully taken it on board. That’s why Wade was more upset when he recounted the impact on his family. That’s trauma. That’s stuff that he experiences as a bad thing. The remembering of it is upsetting. But for these guys, this is what conflicts them so much, this is what they grappling with. Remembering the abuse is this weird mix of the hindsight that this was abuse and someone taking advantage of them when they were children, but also the print memory of that moment of how good it felt. And that’s the headfuck.

Have other accusers contacted to you?

No one has come forward yet. This is not a decision that anyone makes casually. To break the silence of years or decades then type an email to a documentary producer, that’s not an easy thing to do. You have to tell your mom, tell your dad, tell your wife or partner. People who have been molested by Jackson haven’t just come out of the bushes running. It’s not that kind of party. It’s gonna take a long time. If anyone does come forward, to reconcile and make peace with their own families and themselves and they may not want to do that in public. It’s not like a plane crash where people are like, “Hey yeah, I was there too.” The constant theme of this is trying to understand the psychology of child sexual abuse. It’s really complicated and difficult to understand. My film over the course of four hours tries to elucidate that, but it’s an uphill struggle, especially when people have a preconceived prejudice against these young men and their families.

Is there any talk of a sequel using the footage of the D.A.?

Oh yeah, I would love to do that. The film I would really like to make following this one is the trial of Michael Jackson. I could only do that if the victim and his family participate. It would be a much weaker film [if they didn’t.] I don’t want to follow Leaving Neverland with a weaker film. If Gavin Arvizo and his family would agree to participate, I would very much like to tell the story of that trial. I think it’s fascinating and astonishing that Michael was acquitted. The way that happened is an amazing story and one that should be told. But no, I’m not going to just carry on making Michael Jackson films, that’s not my thing. Like I said, this wasn’t a film about Michael Jackson.

Leaving Neverland is now streaming on HBO Go.