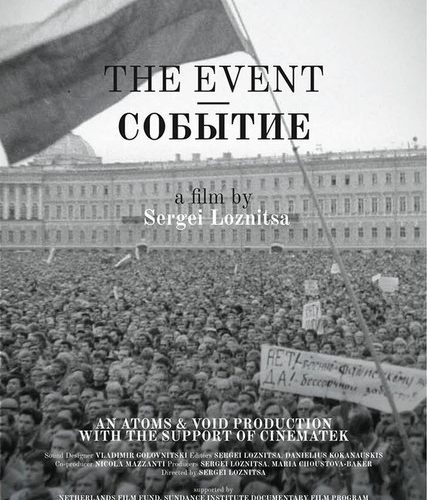

If the films competing for the Gold Lion so far this year have taken an abstract, decorative or glamorized view of the real world, the ones being shown in the out of competition slots seem determined to show us reality. Perhaps the most serious of these movies is Sobytie (The Event). It’s the work of Sergei Loznitsa, a Ukrainian director with sober things to say about Russia as it is today. Working exclusively with archive footage from Leningrad’s Palace Square, Loznitsa takes a reflective look at the attempted 1991 August Putsch — and the public’s response to it — and offers a eulogy of sorts for a different time.

On the 19th, 20th and 21st of August 1991 a group of high-ranking Soviet Party members — led by KGB Chairman Vladimir Kryuchkov — attempted a coup d’état in the Soviet Union’s capitol to try and take down president Mikhail Gorbachev. The group, which acted under the name GKChP (State Committee on the State of Emergency), distrusted Gorbachev’s concept of Perestroika, which looked to restructure the Soviet Union. The KGB worked to detain a number of people for the group but SFSR president Boris Yeltsin managed to stay free. He urged the army not to get involved and so the citizens decided to intervene. This opposition rallied in Moscow, but in Leningrad the atmosphere was far more subdued.

Loznitsa’s film documents this unsure time with remarkable clarity. He shows the hushed crowds in St. Petersburg and captures the jarring mood of uncertainty. We see the first barriers being erected, and the first pamphlets being issued. The GKChP put out new broadcasts on each day of the coup, and the director shows the live moments when the citizens listen in. Earlier this week Frederick Wiseman showed real people’s reactions to real problems in his remarkable film In Jackson Heights. All things considered, the issues here are far more urgent, but the temperament is much different too. Russia was only just emerging from the Soviet era and the anxiety in the film is palpable. Crowds gather to fill St. Petersburg’s Palace Square and the nerves amongst the mob are telling. The imagery later on in the documentary also proves to be powerfully moving. It’s so cinematically shot that you almost sense it might be staged, but it’s not.

The best of these moments comes when the people raise their arms for a minute’s silence, making the two-fingered symbol for peace. The cameraperson scans the crowd, and shoots it from their level, allowing us to see the slow cautious spread of what once might have been a dangerous idea. Later on something even more interesting happens. We see people climb the great gates of the winter palace to get a better view of the people speaking. These are the same gates that were scaled in the 1917 revolution when the palace was stormed and the Tsar was killed, and the same gates that we saw when Sergei Eisenstein depicted the revolution in his 1927 film October. An old image of power and revolution recycled — an incredible visual lineage.

An even more interesting lineage in Sobytie might be the music. The GKChP took control of both the radio and television stations for the duration of the coup and used them to broadcast their literature on air. All other stations were cut off and replaced by a loop of the Bolshoi Ballet performing Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. It is said that to this day many Russians who were alive at the time still have a Pavlovian response to the music. Loznitsa brilliantly opens each chapter of his documentary with successive movements from the ballet, building to a wonderful crescendo for the final scene.

It all works to provides an image of a new dawn in Russia, or perhaps one that might have been. Another great shot shows a man taking down the soviet flag from the roof. He folds it up — seemingly out of sight of the crowd and relatively oblivious to the staggering significance — as the Russian tricolor is raised. The orator in the crowd talks about creating a new Russian flag, and that the tricolor will only fly for the time being. Of course we now know this won’t be, but the sentiment rings true. Loznitsa’s film seems to say: look at this spirit! What have you done with it? Where did it go?

The director should know as well as anyone after all. In the press conference, Loznitsa reminded those present that just two weeks ago Oleg Sentsov, another Ukrainian filmmaker, was sentenced to 20 years in prison for allegedly planning terrorist attacks in the Russian annexed Crimea, a trial that Amnesty International compared to those of the Stalinist era. During the credits of Sobytie the director reminds us that many of the old party members retained their positions after the fall of the Soviet Union. This melancholic, meditative documentary suggests that the slate should have been cleaned at the end of that era, and that the repercussions of not doing so are still being felt today.

The Event premiered at the Venice Film Festival.