Curtain raisers seldom come more bombastic than the last two films to open the Venice Film Festival, Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity in 2013, and Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman last year. Attempting to maintain that level of volume this year on the Lido is Icelandic director Baltasar Kormákur’s Everest, a grand-scale, by-the-numbers 3D epic about the doomed 1996 expedition to climb the titular peak. The performers play it strong, but one feels the air is a little thin.

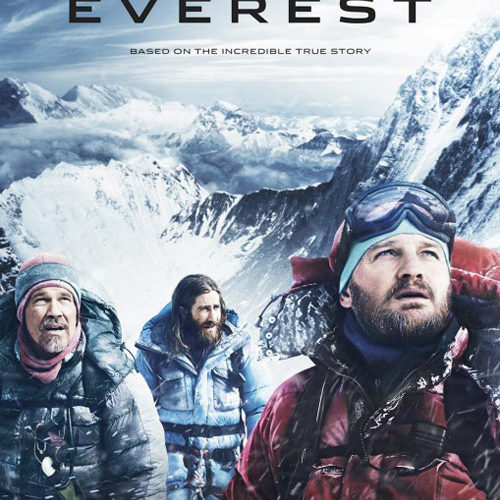

A confident, healthy-looking Jason Clarke leads an all-star cast as Rob Hall, a New Zealand mountaineer who, in the early 90’s, began to run commercial expeditions to take amateur climbers to the summit of Mt. Everest. We open on one such expedition as military-sounding drums pound on Dario Marianelli‘s score. In the 5 years prior to this 1996 expedition, Hall’s outfit Adventure Consultants have led 39 mountaineers to the top without a single fatality, a service which now carries the price tag of $65,000 a head.

The latest crop features a brash Texan (Josh Brolin), a blue collar gent (John Hawkes), a Japanese woman who has climbed six of the seven peaks (Naoko Mori), and a journalist for Outside magazine looking to write a piece (Michael Kelly). The rag-tag ensemble is out for adventure at the ends of the Earth, but it’s looking like anything but. Hall’s eye-watering prices have apparently attracted other industrious types to the party, and base camp (with 20 competing groups squeezed in) now looks more like a wintertime Burning Man festival than somewhere 6,000 meters above sea level. The factions soon begin to squabble over ladders and climbing rosters. The wind has picked up and the writing is on the wall.

Offering just a dash of pathos to proceedings is fellow mountaineer Scott Fischer, played by Jake Gyllenhaal (who, despite being billed in many places as the leading guy, instead is found slightly subdued in a supporting role). Fischer was the leader of a more free-spirited climbing association called Mountain Madness, and a yin to Hall’s more commercial yang. We see a certain warmth between the two men, if not necessarily a respect for each other’s methods.

This conflict between Hall and Fischer only threatens to reference the real elephant in the room here: the question of hubris, be it Hall’s place on the mountain or perhaps anyone else’s. At one point one of Fischer’s colleagues, a hard contemplative Russian bloke named Anatoli (Ingvar Eggert Sigurðsson), remarks that “the last word always belongs to the mountain.” It’s the sort of admission that Everest‘s script, from Simon Beaufoy (127 Hours) and William Nicholson (Gladiator), seems to lack a lot of the time; a sort of Herzogian spiritual acceptance that this is indeed a violent inhospitable place, and one that has a tendency to leave humanity looking rather futile.

A good forbearer for this film might have been Kormákur’s 2012 Icelandic film The Deep (Djúpiô), another movie about human endurance, focusing on the true story of an Icelandic fisherman who swam for 6 hours in the north Atlantic after his trawler and crew sank. It takes place about 6 kilometers lower than Everest‘s base camp, but thematically it’s not a million miles away. Kormákur seemed to uncover much more in that man’s struggle, about how the mind might operate in such close proximity of death. While out in the freezing ocean waters the fisherman ponders the strangeness of his environment, and finds some sort of catharsis through it. By comparison, and quite regrettably, Everest only seems to seek this through the more American model of male camaraderie and personal achievement. It’s a rather shallow climb indeed.

Everest opened the 2015 Venice Film Festival and arrives on September 18th.