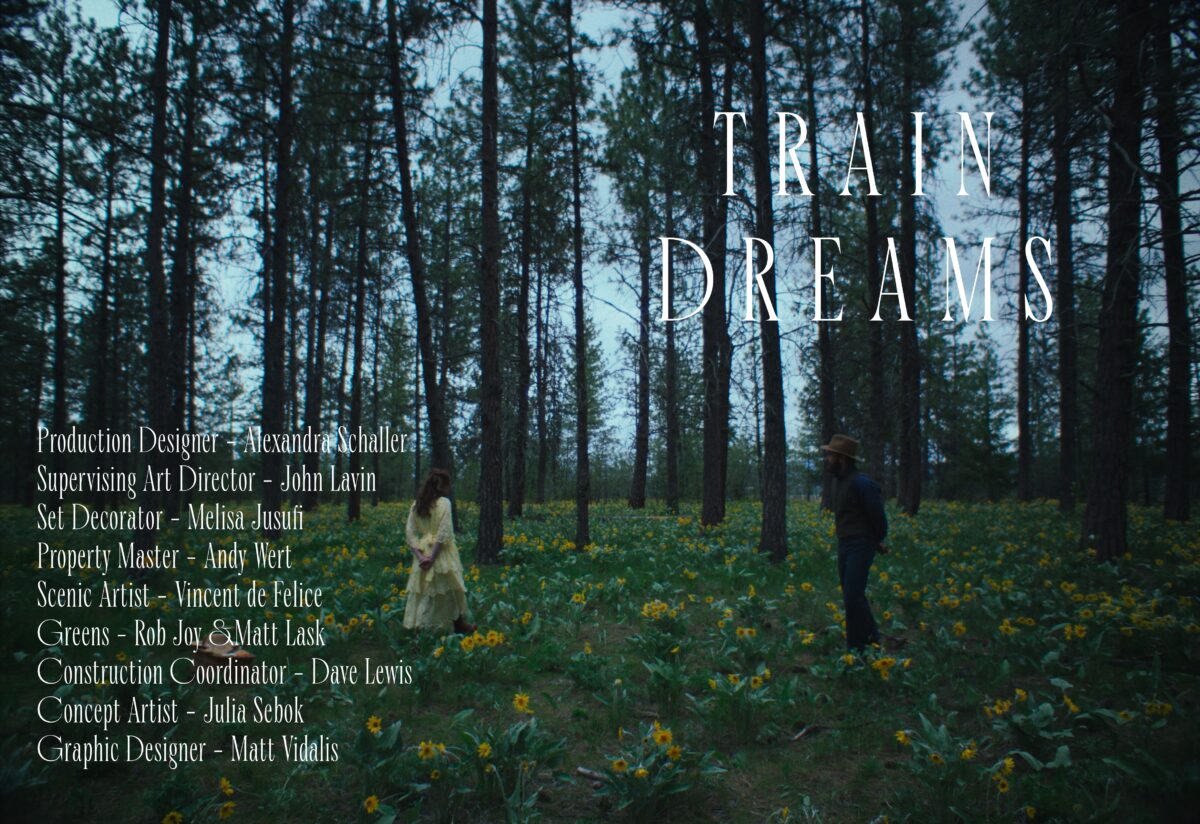

One of the many special things in Train Dreams, directed by Clint Bentley, is the production design. Nearly every element of each setting feels like it was just sitting there, waiting to be captured. Of course, this is not the case. It was meticulously, carefully planned and built. The Film Stage was lucky and honored to speak with Alexandra Schaller, the film’s production designer, about the agonies and ecstasies of bringing Train Dreams to life, as well as some earlier, accomplished work in her career.

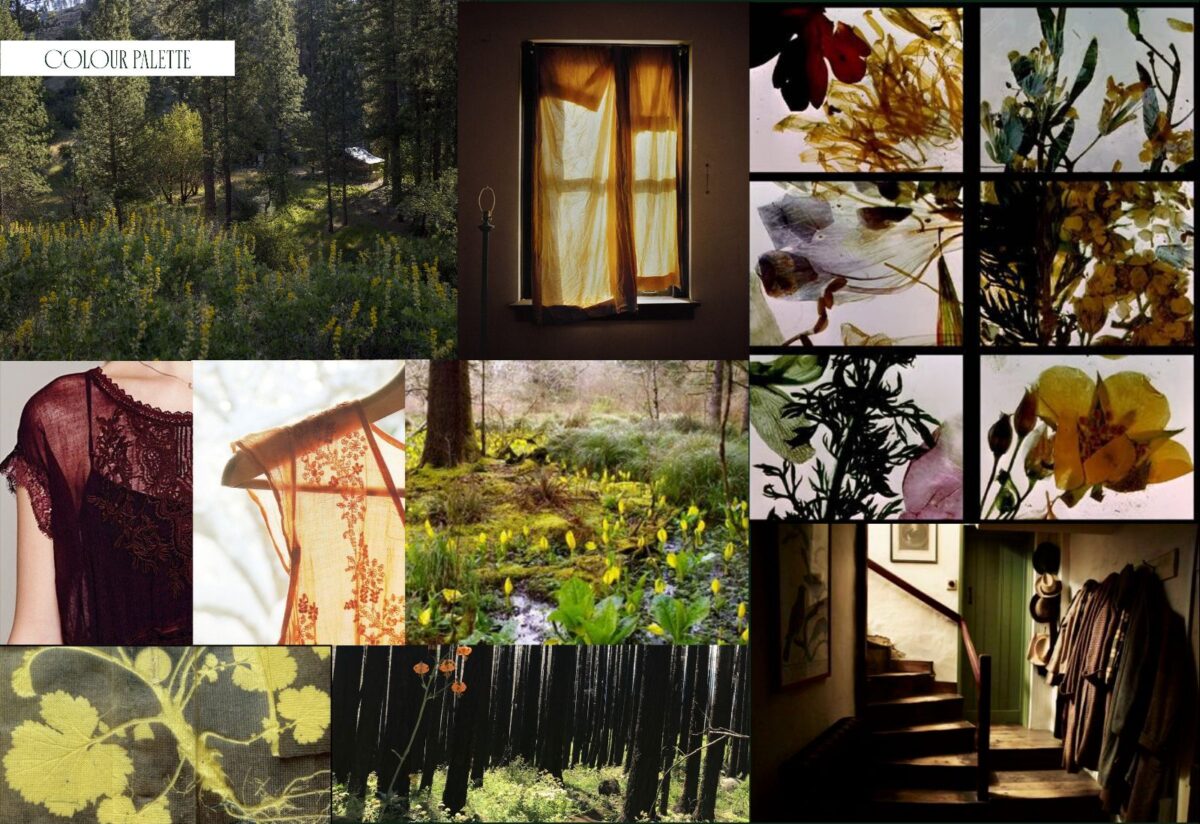

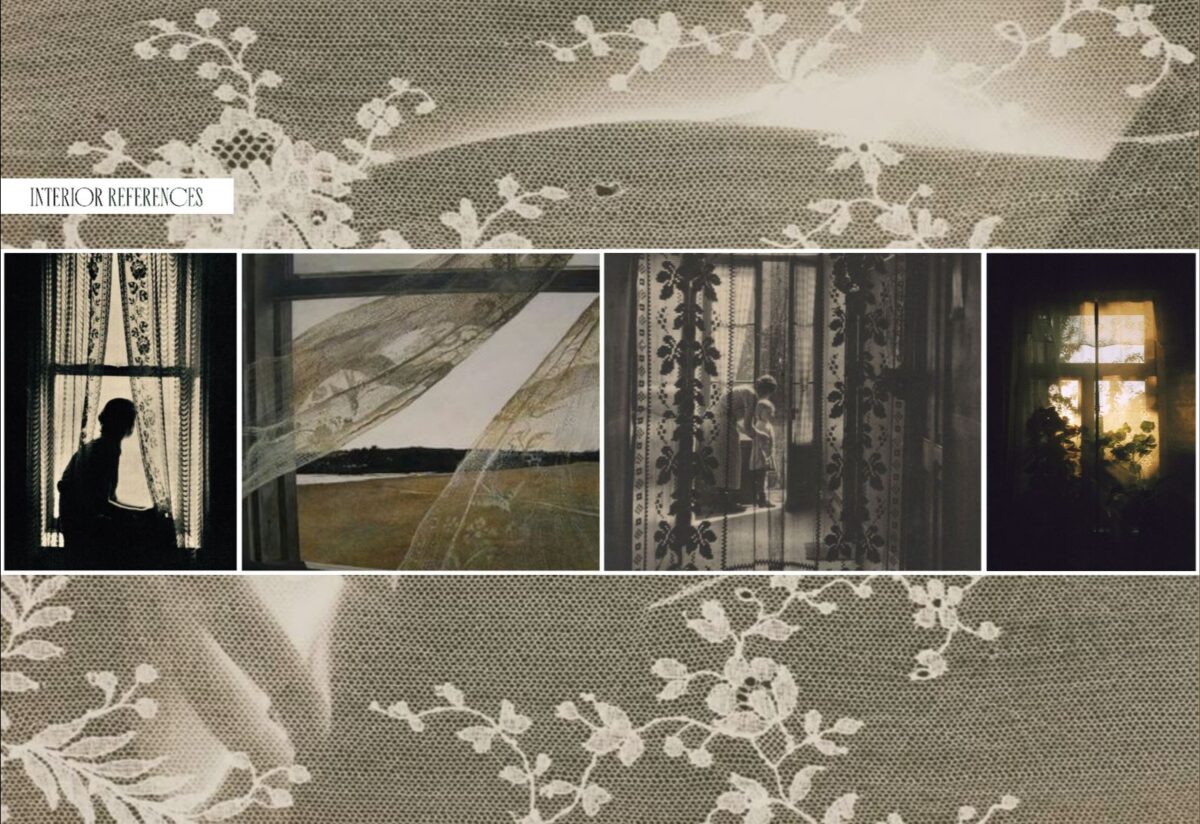

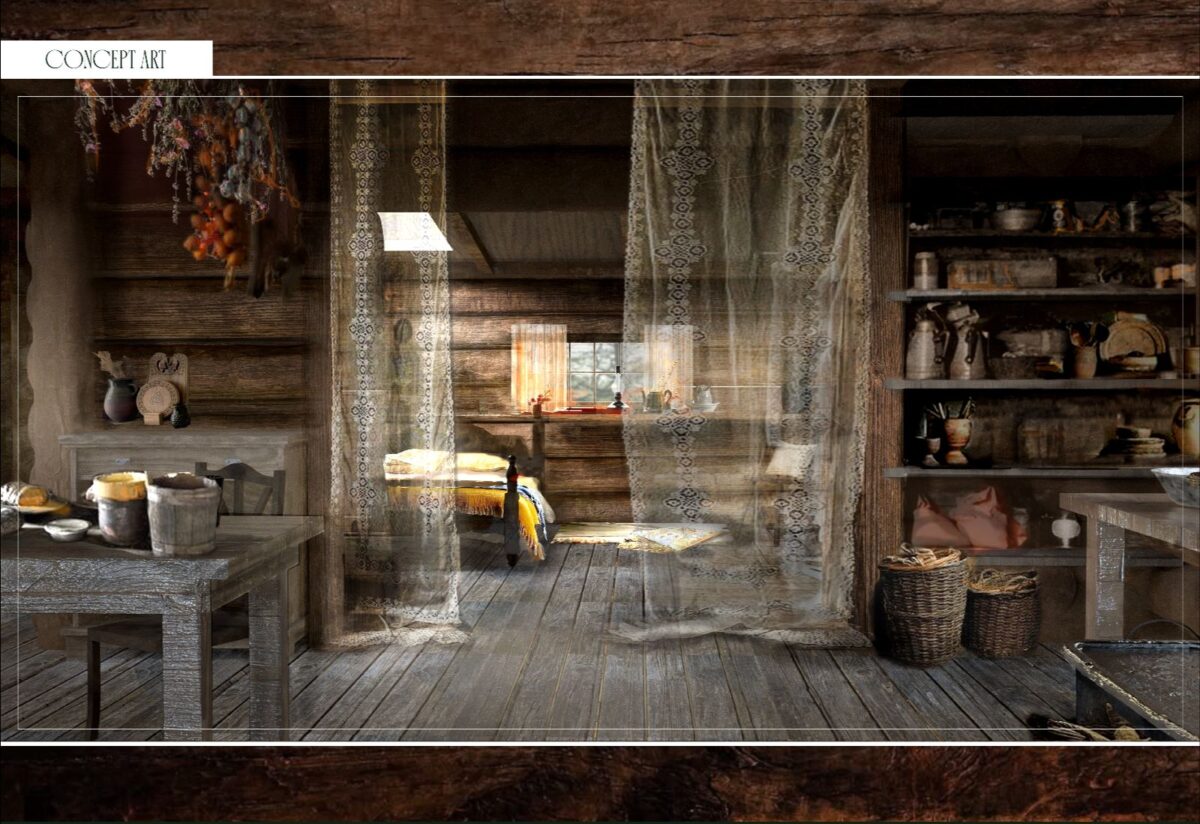

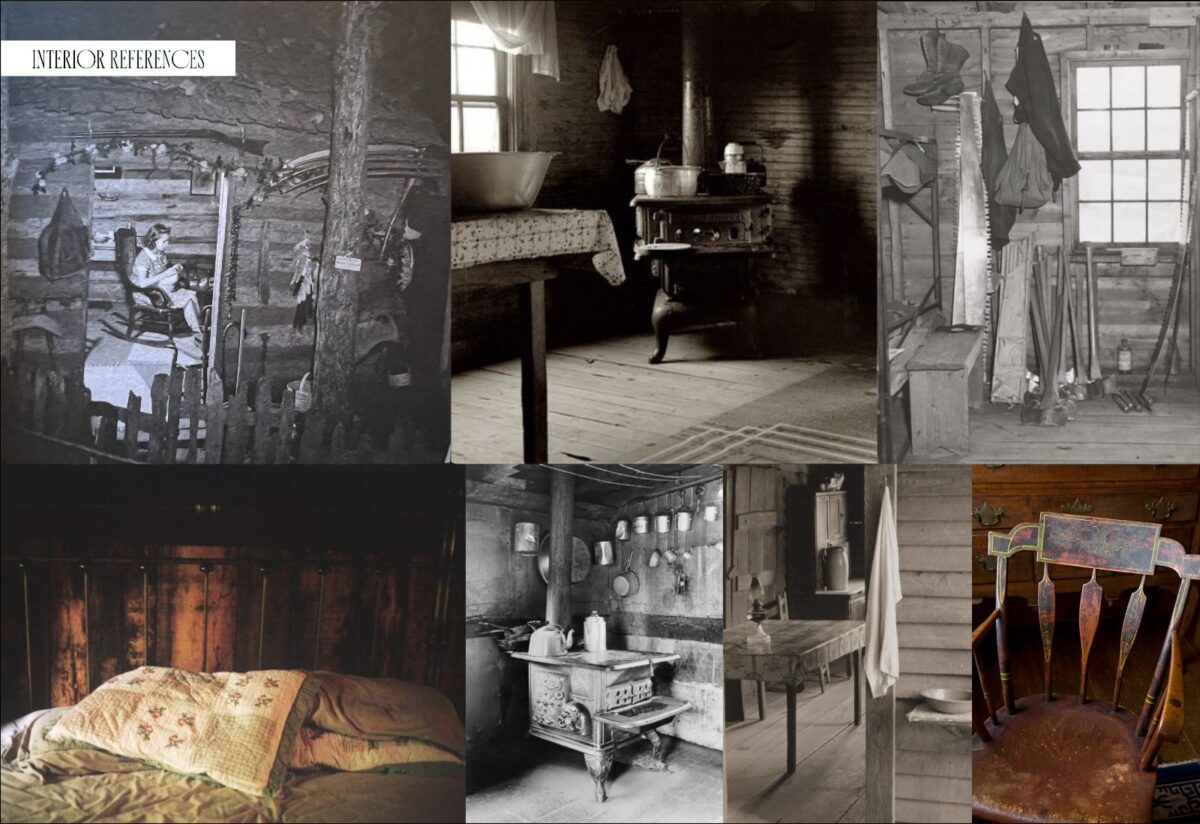

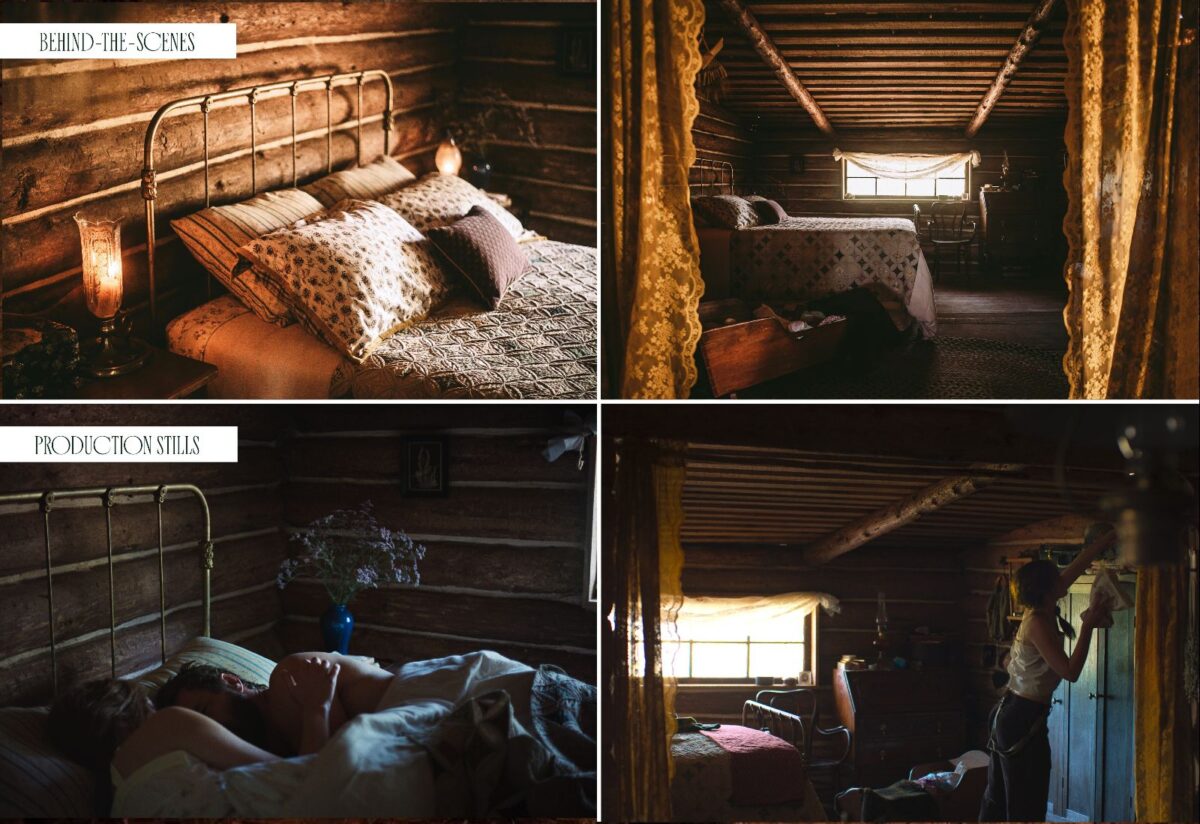

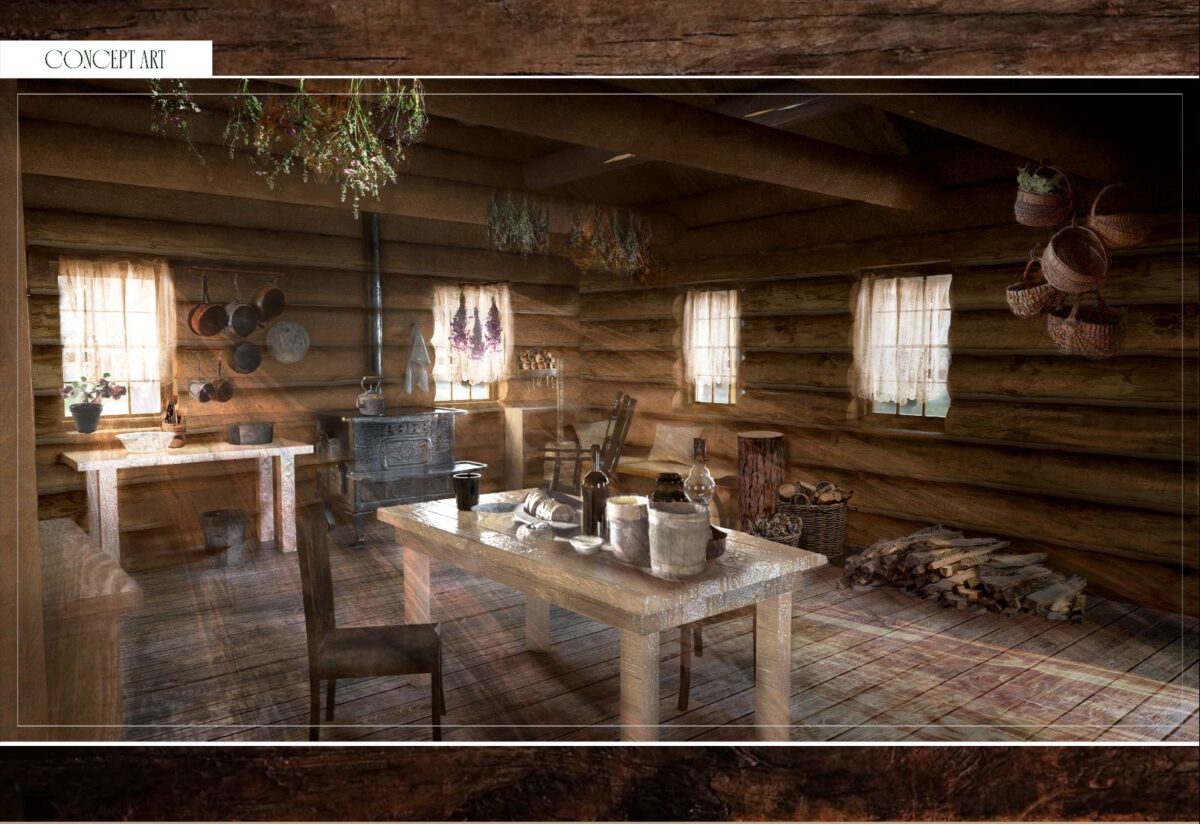

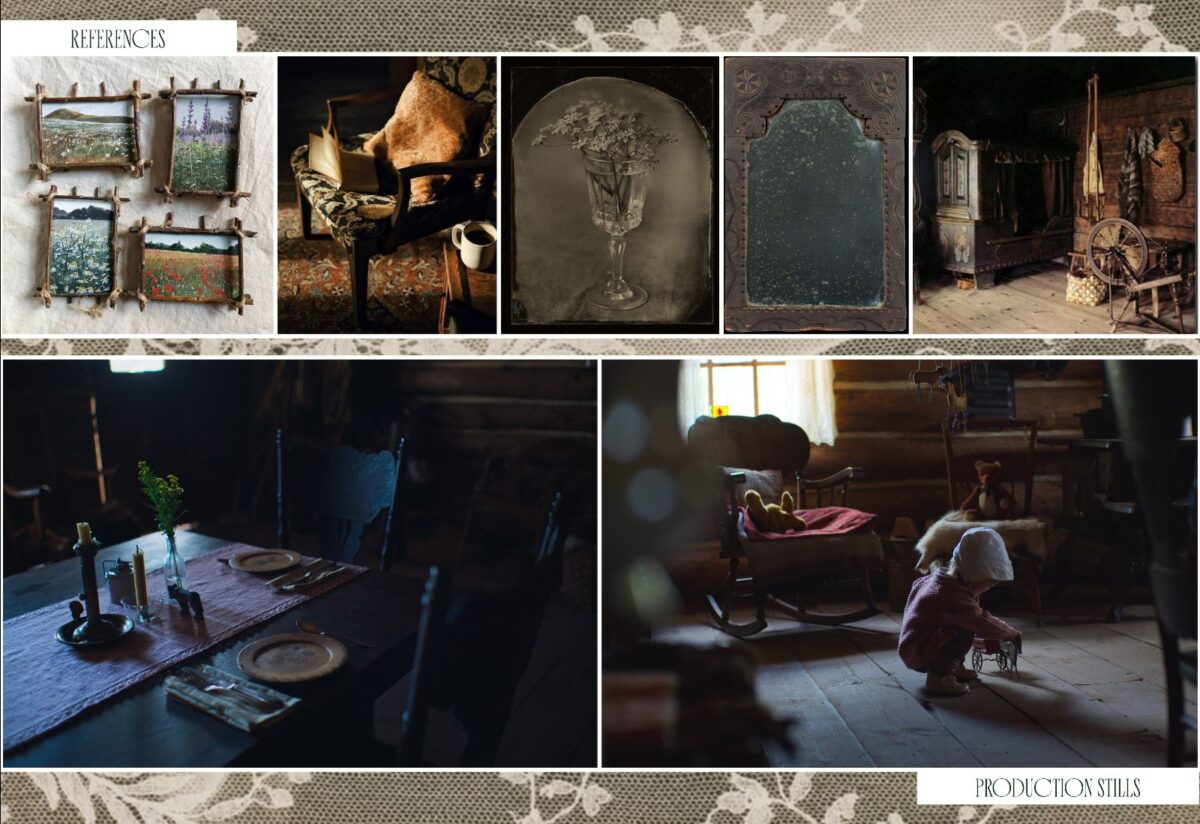

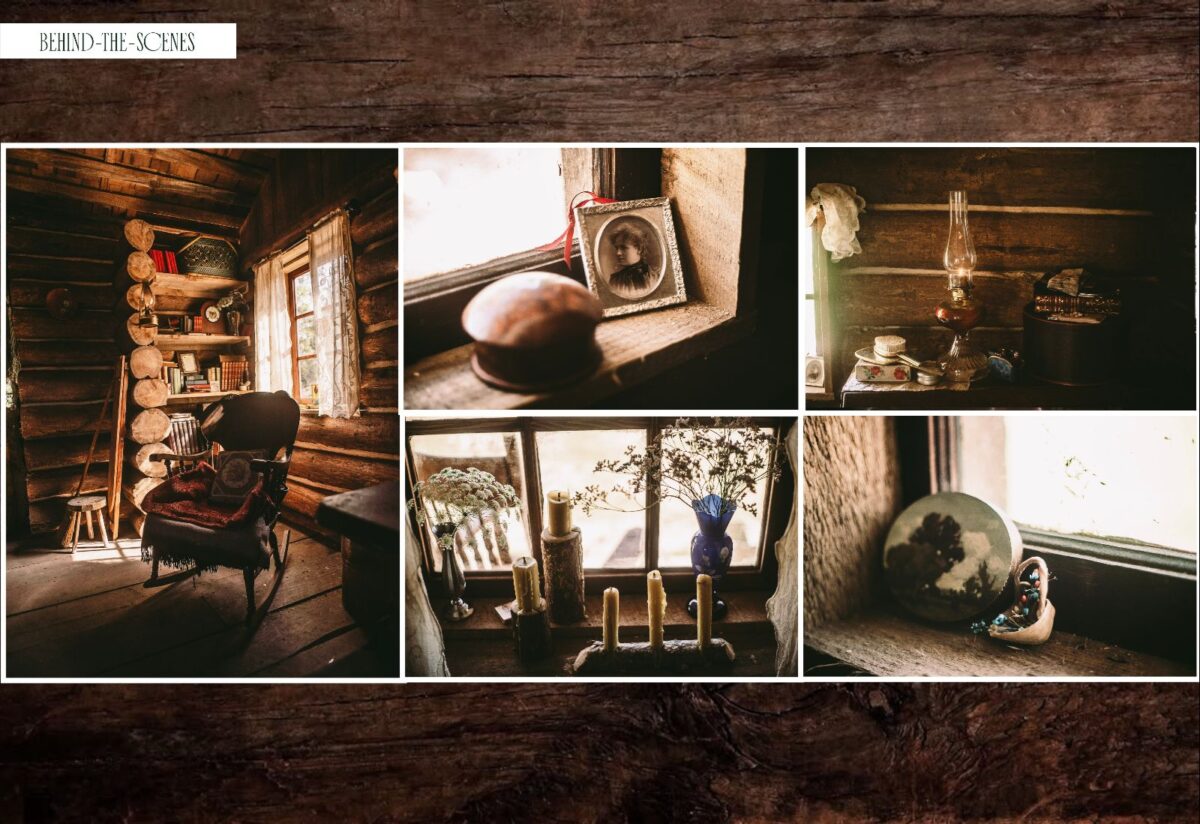

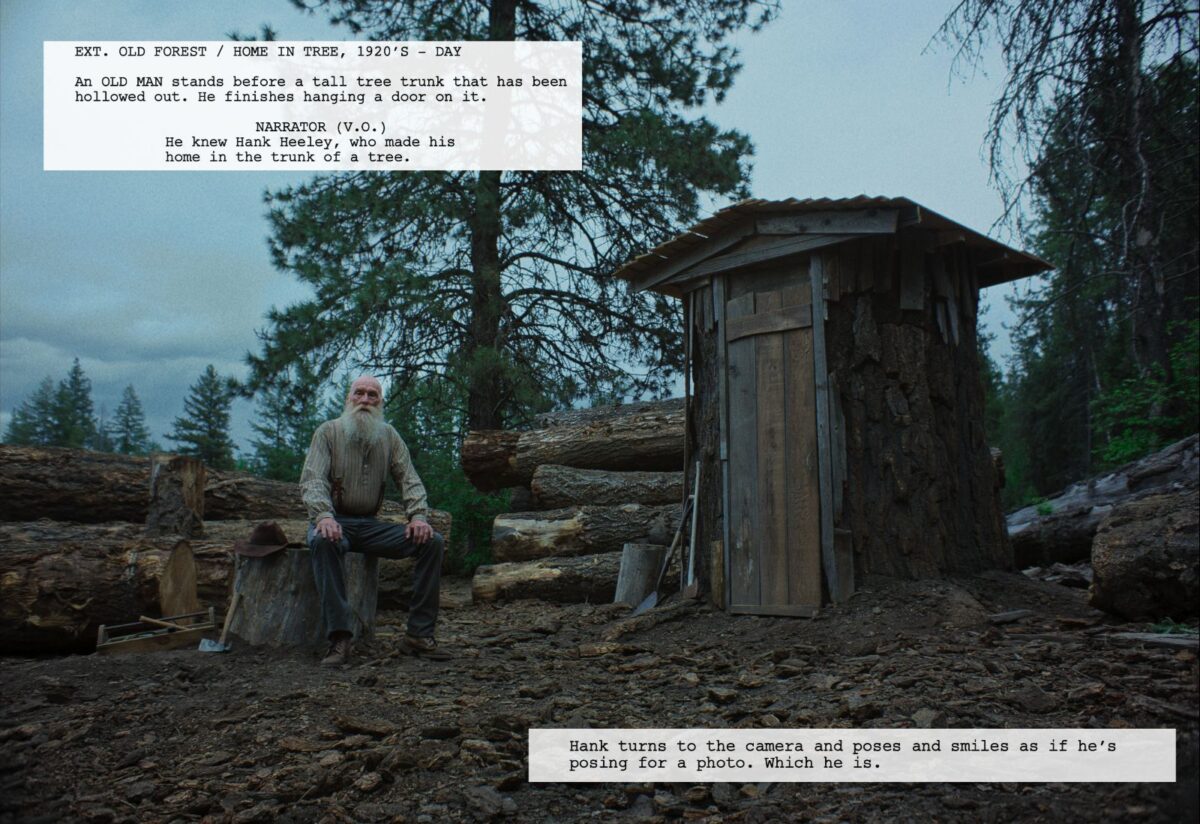

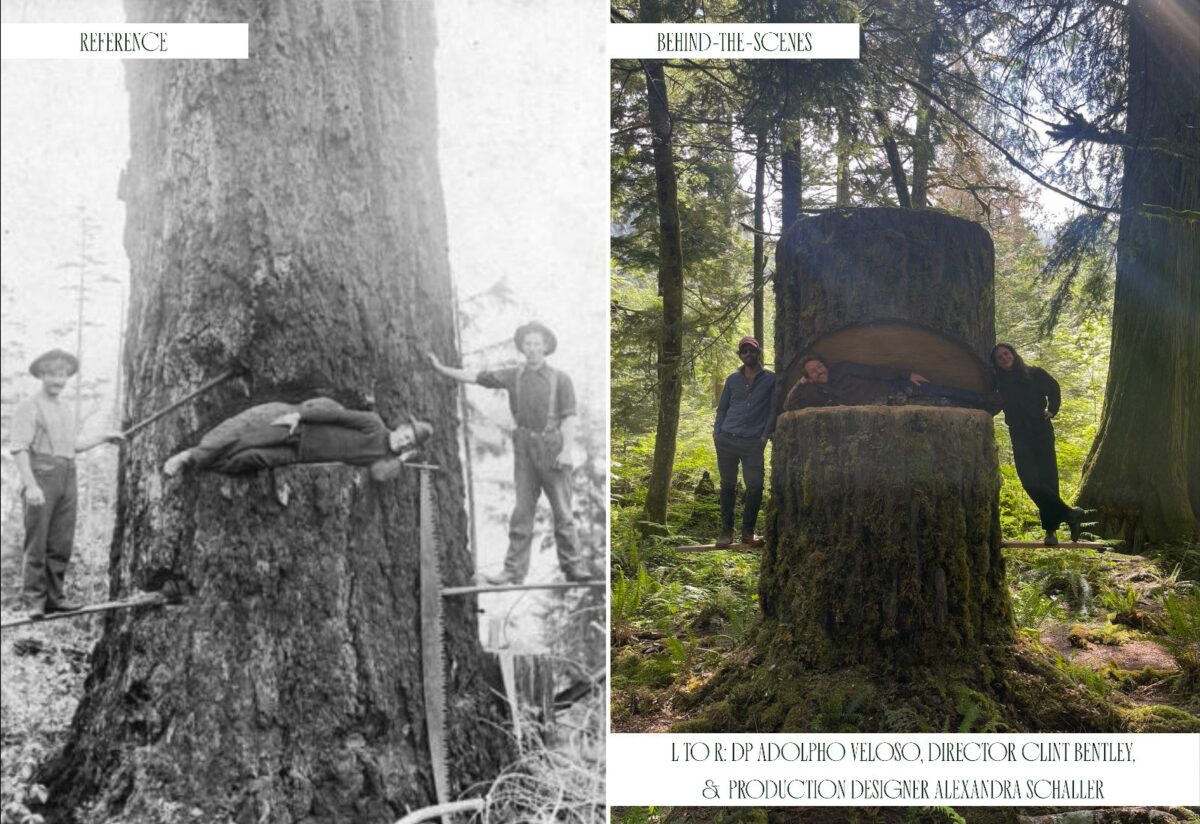

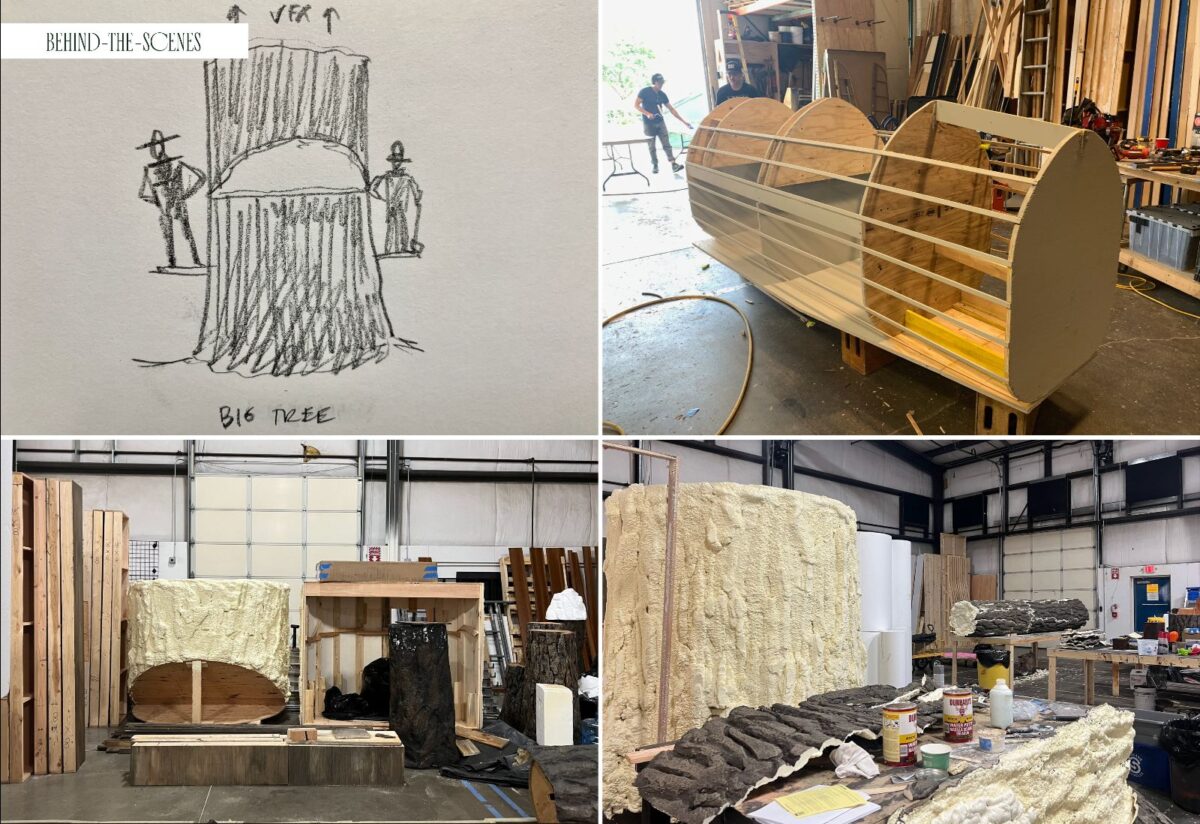

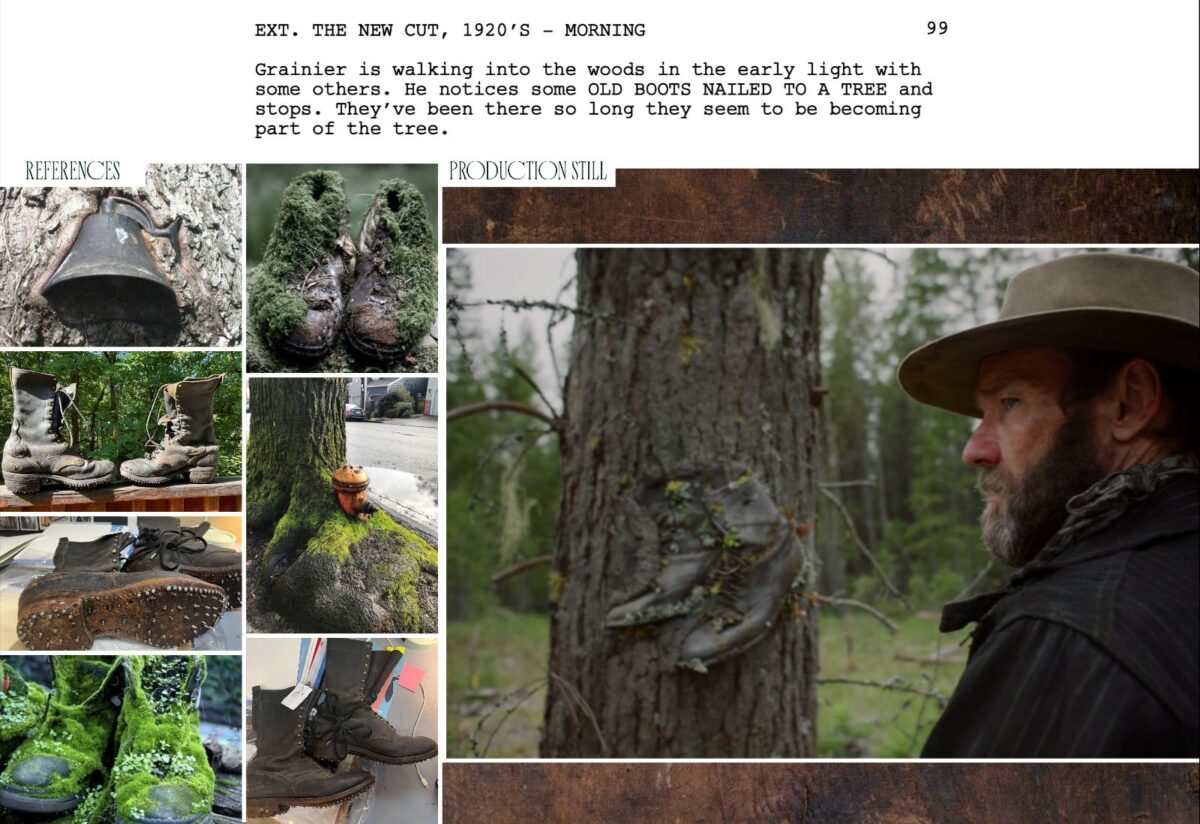

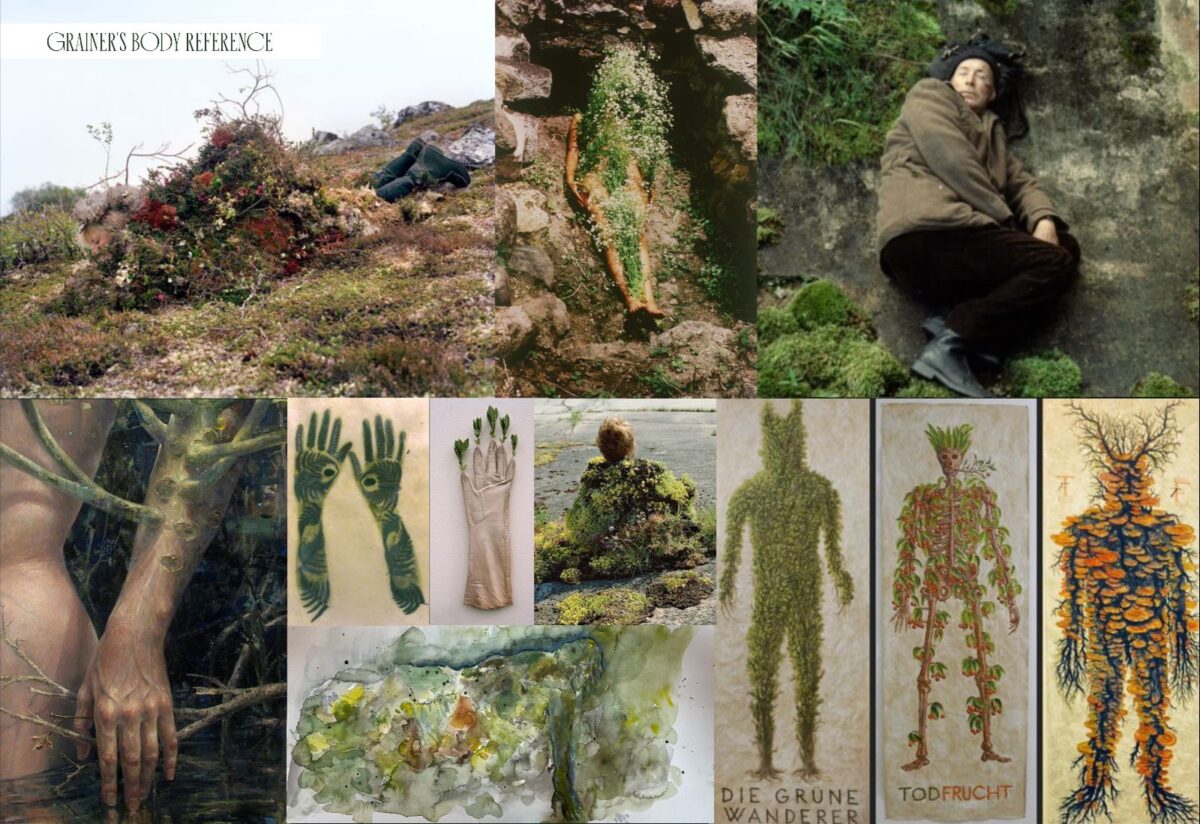

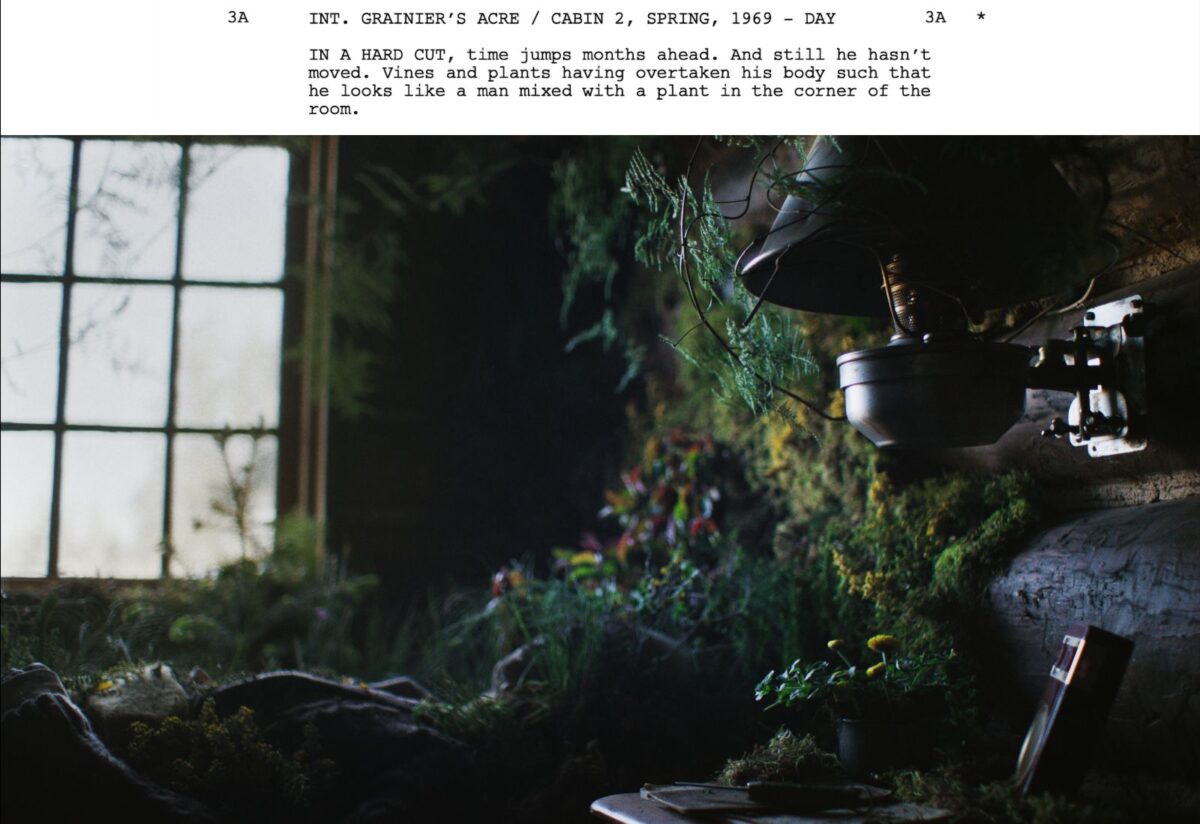

Additional thanks to Schaller, who provided The Film Stage access to mood boards and behind-the-scenes photos from the project, featured below throughout the piece. This interview has been edited for length and clarity, and the full audio is also available to listen below.

The Film Stage: Train Dreams is based on the Denis Johnson novella. It stars a bunch of great people, including Joel Edgerton. We know all of this. One thing that occurred to me, even writing the review months ago, thinking about the movie, was how did you guys do this, actually? It’s one of these movies [where it’s] a small film but there are these quite grand sequences. And from a production design standpoint, I don’t even understand it. Where did you even start with achieving this?

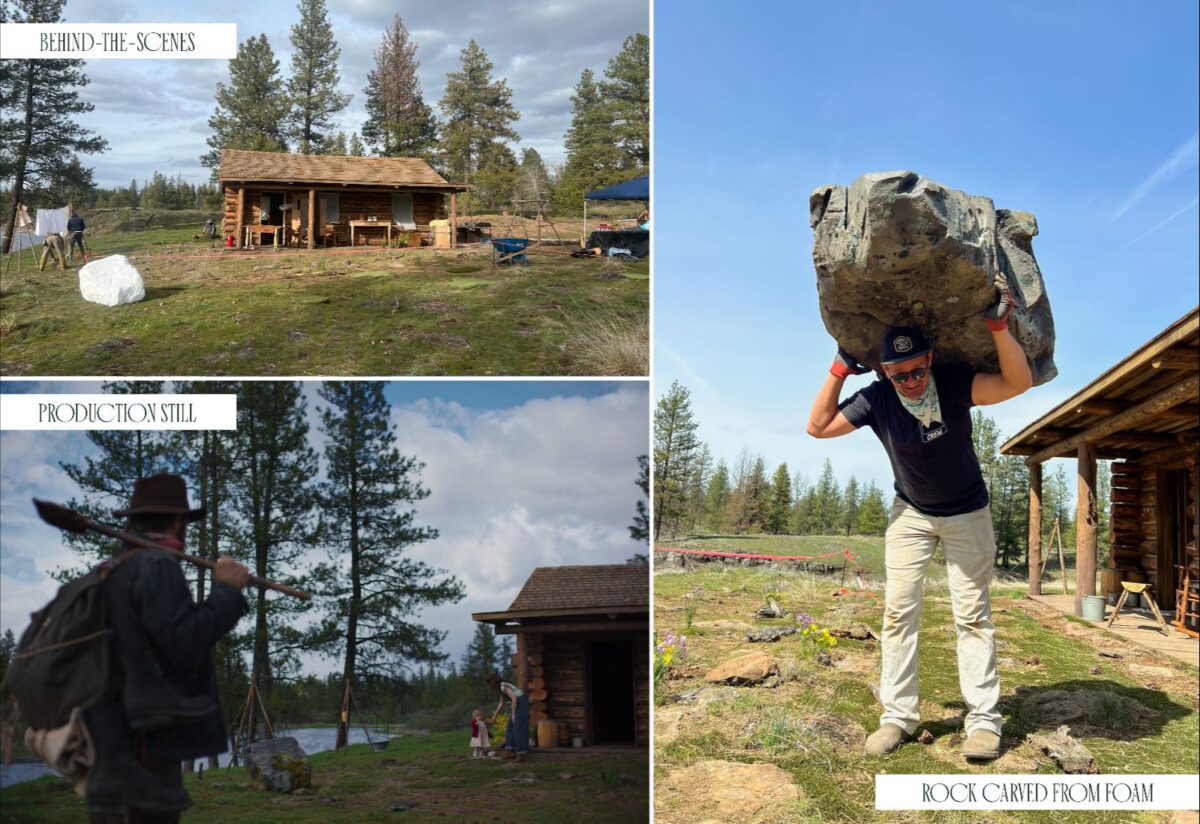

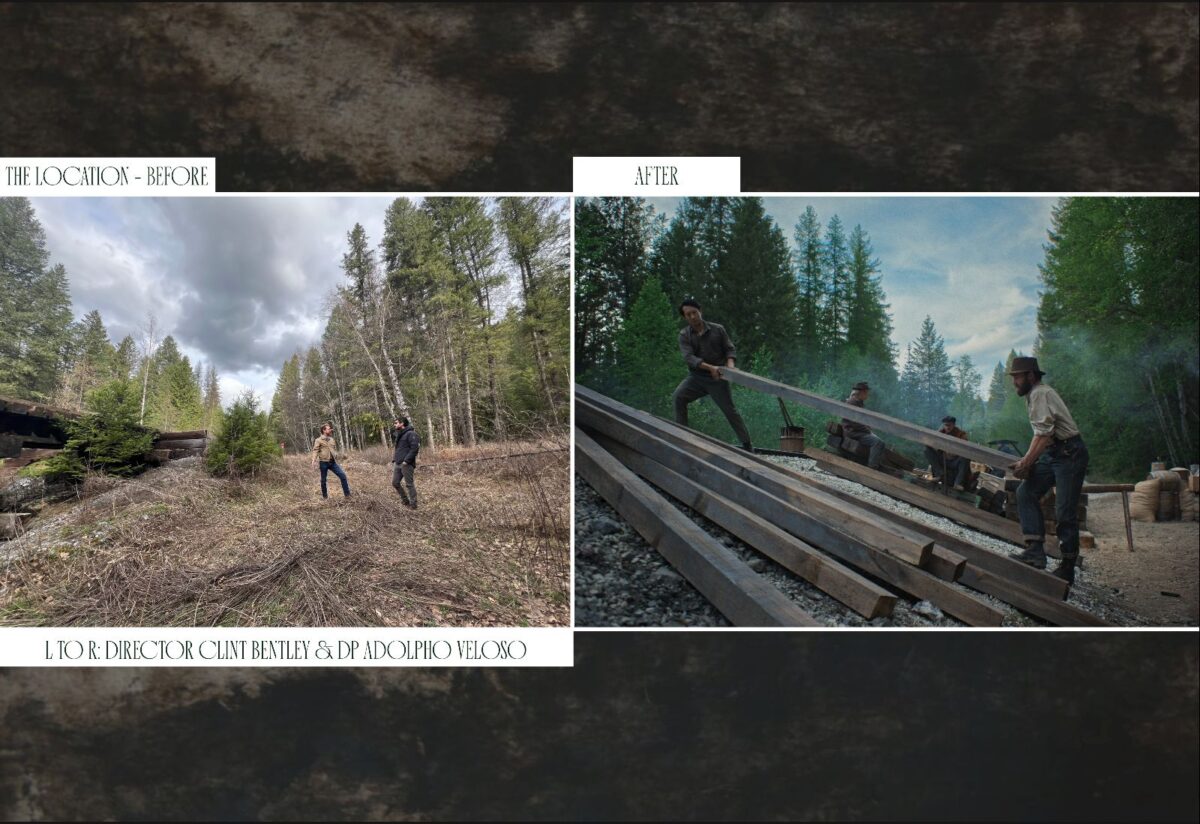

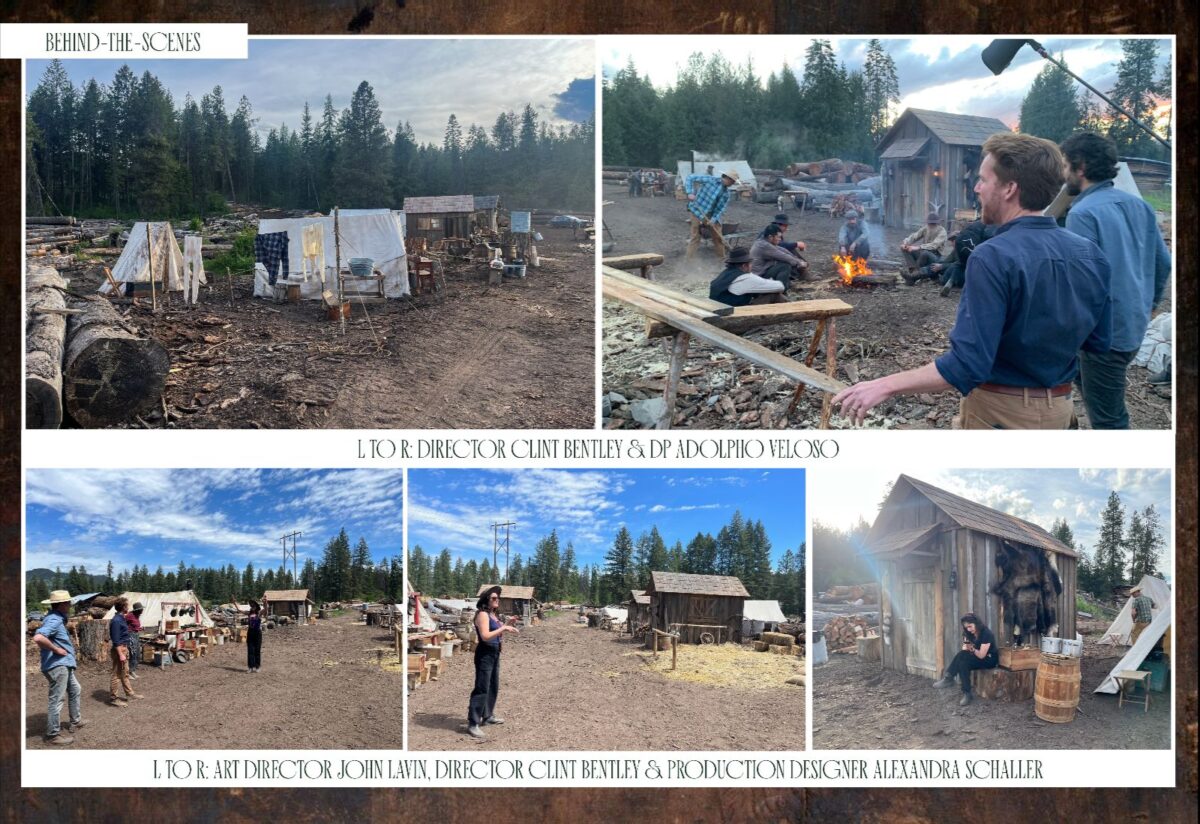

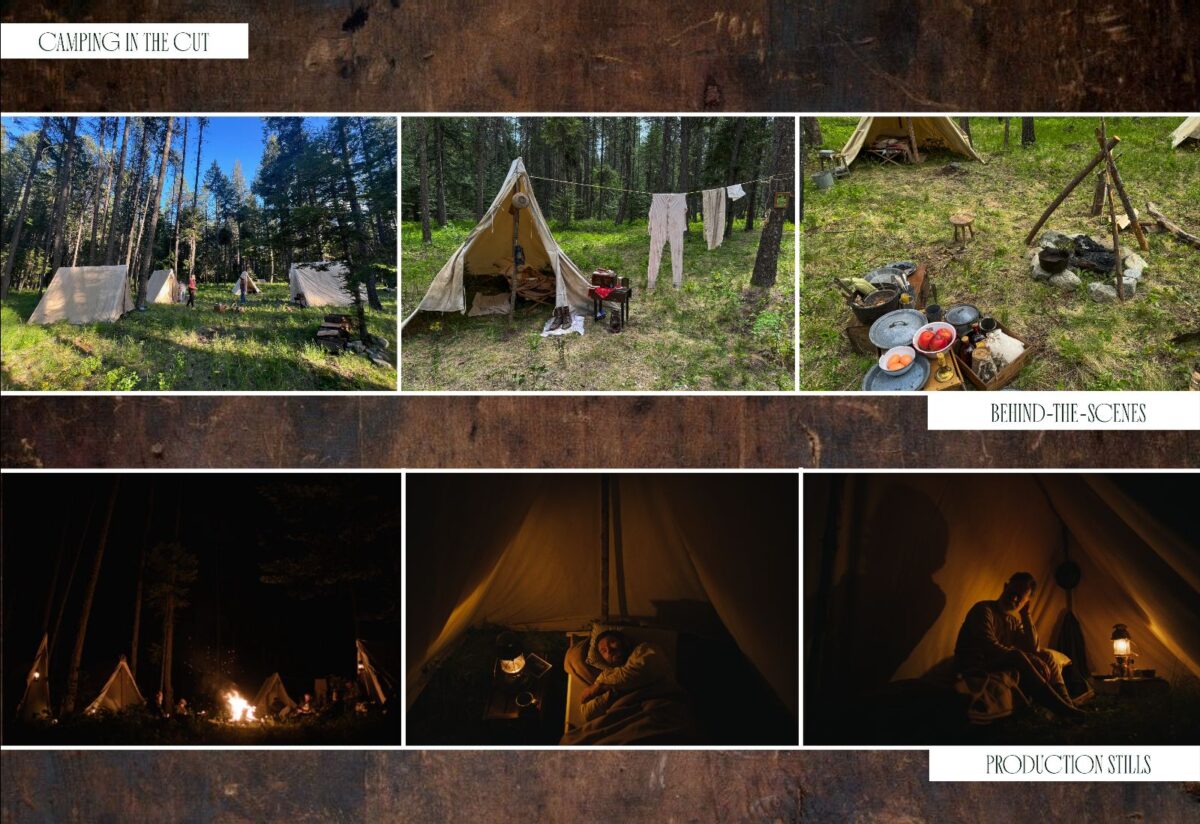

Alexandra Schaller: We did start out with very grand ambitions, and I think that nobody at the outset really knew how to do any of it. It really started with talking to Clint [Bentley] about how we wanted the movie to feel. Right. Because I feel like when you’re at the beginning of something and you see all of these things ahead of you that you have to do, it can get really overwhelming. And so for us, it was really important to drill down on the essence of what we’re trying to say and the kind of movie that he wanted to make, and so, the way that he wanted the world to feel really determined how it should look. It was really hard. One thing that we knew from the very beginning––because I had a very wonderful working relationship with Clint and Adolpho [Veloso], the cinematographer, and the costume designer [Malgosia Turzanska], actually a long-time friend of mine––is we worked very, very well as a unit. And I think that symbiosis can be felt in the final product. We knew from the outset that Adolpho and Clint wanted to shoot natural light, almost no movie lights at all. And so we were able to re-allocate some of those funds towards building some of these very extensive sets and environments that we had to build, because the scope of what we did far exceeds its budget for a movie of that size. Once we figured out how we wanted it to feel, it was really about casting the right locations in terms of the natural beauty, because we realized that we wanted to do all of our builds on location as opposed to in a studio.

Wow. Yeah. So there was no studio stuff, really?

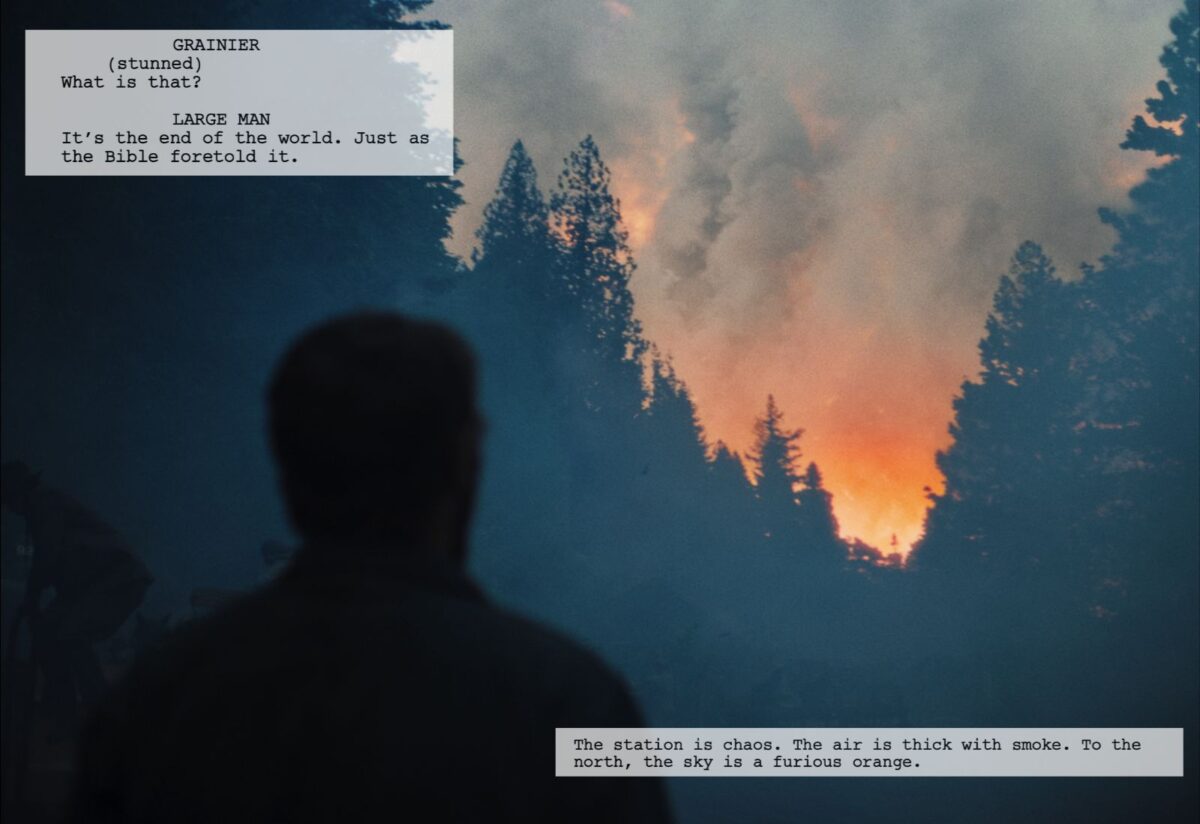

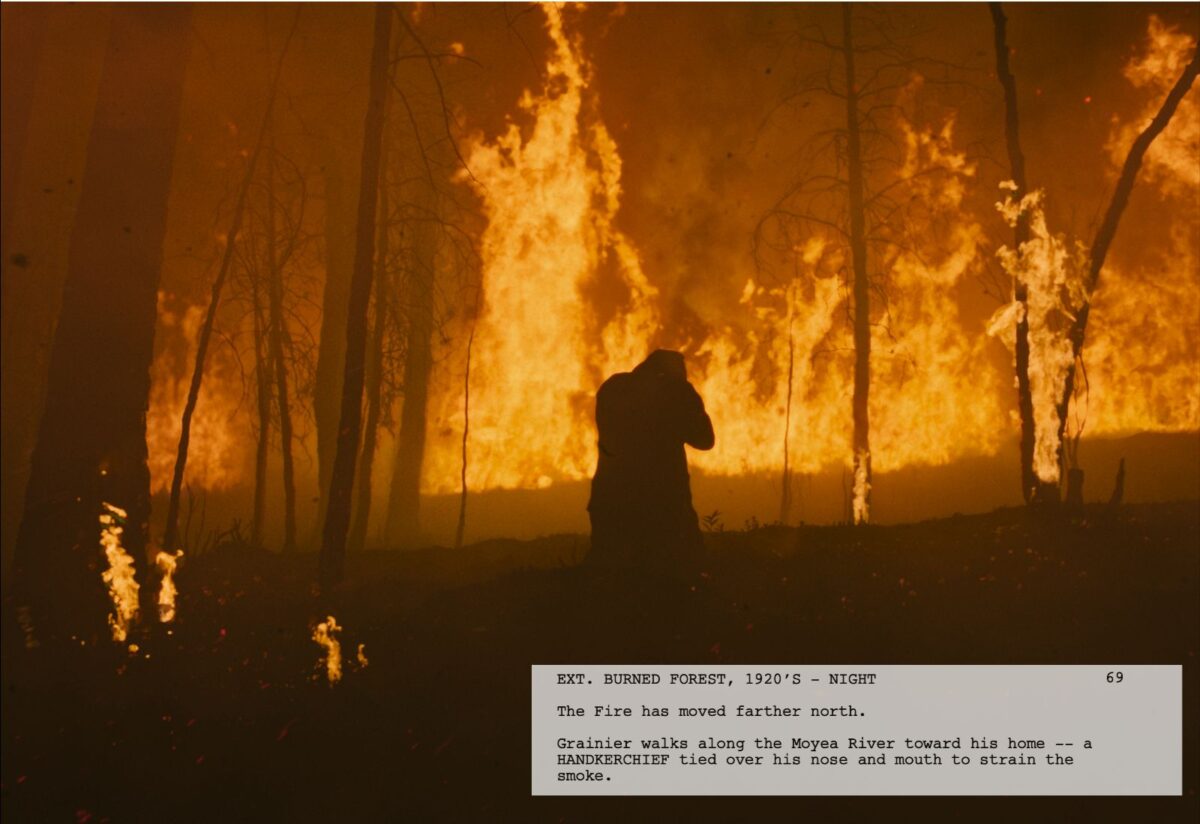

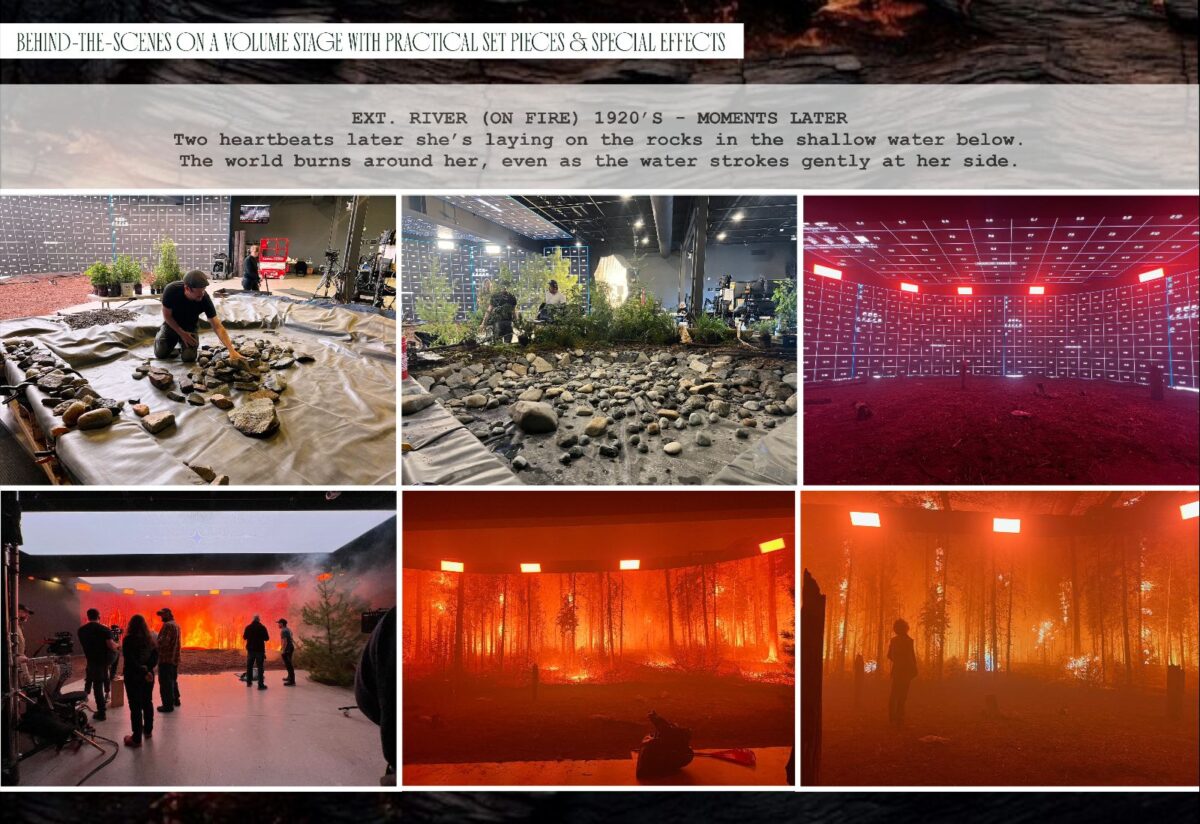

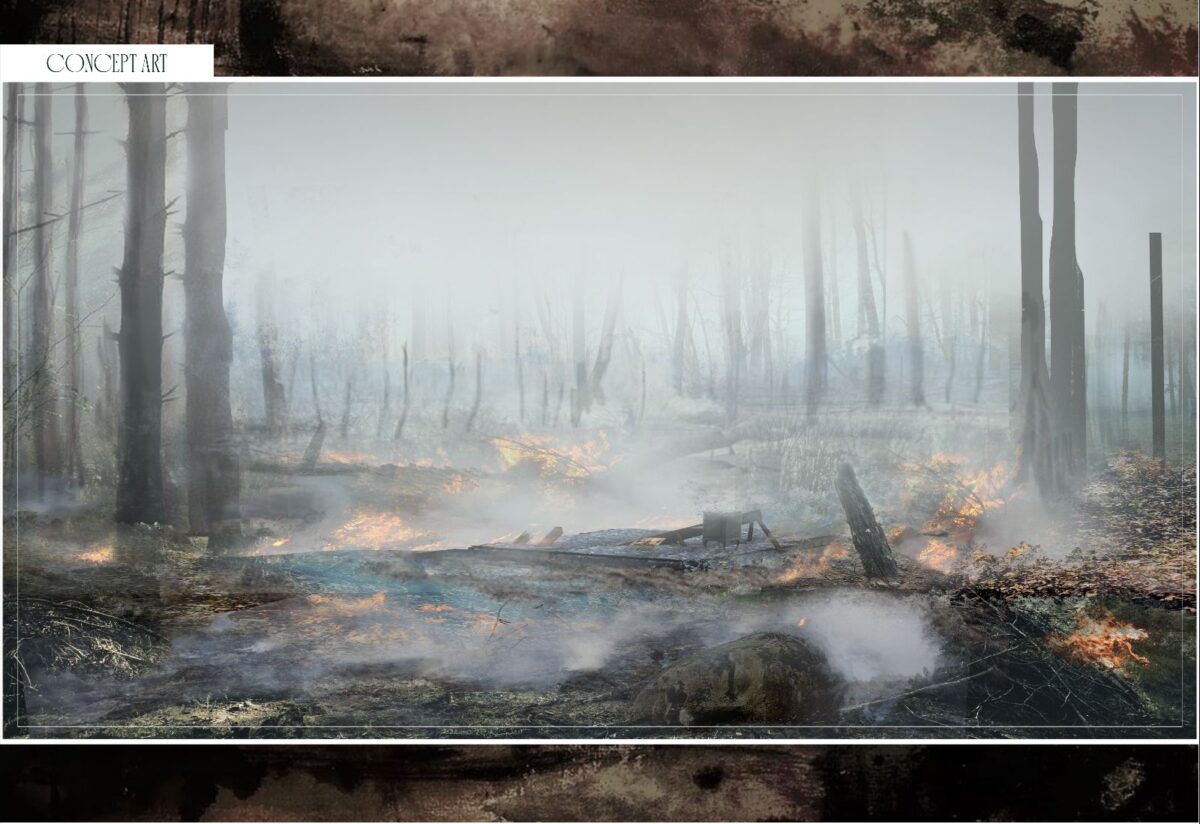

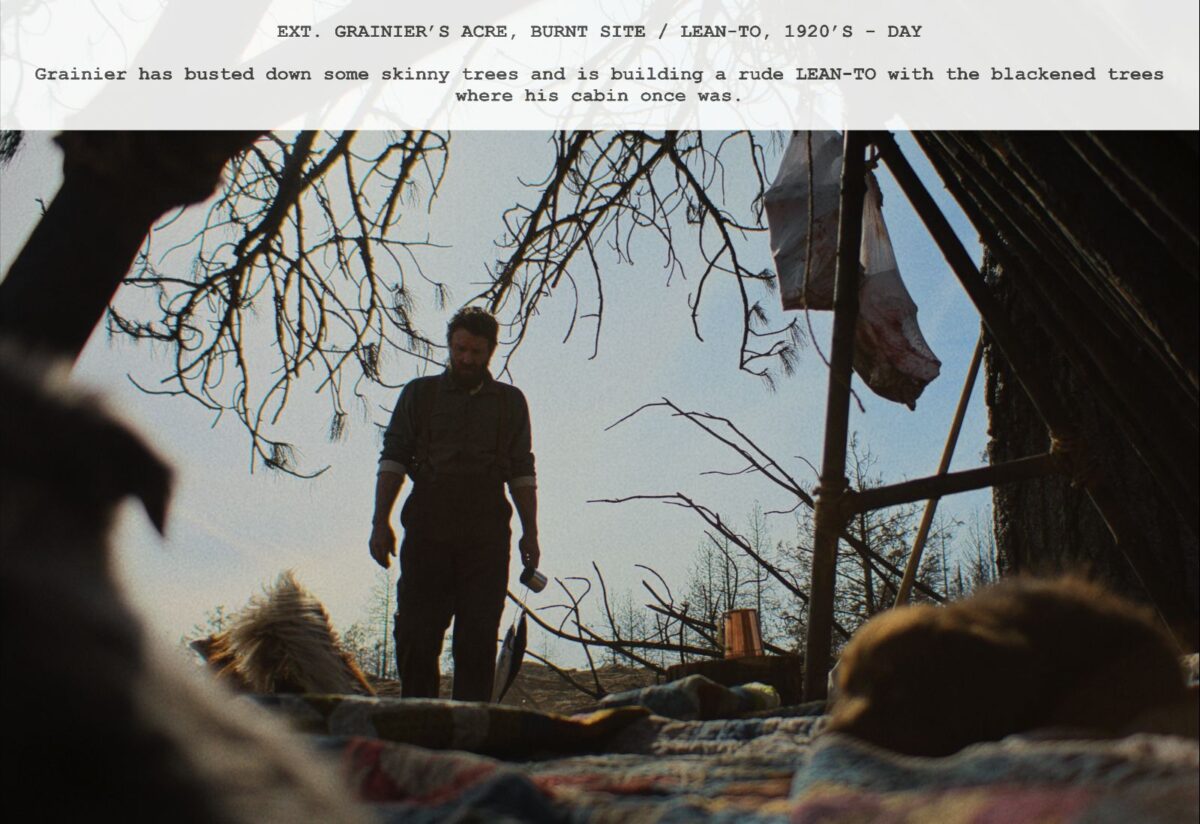

One brief section of the fire was on a stage, on a volume stage, but we shot the fire. It was mostly a practical burn of the cabin. And then we did some work with lighting for the fire and VFX supplementation in a real forest. And then there’s a portion of it with Gladys and his memory of Gladys’s death that we shot on a volume stage. But everything else was on location.

What was the hardest build or sequence?

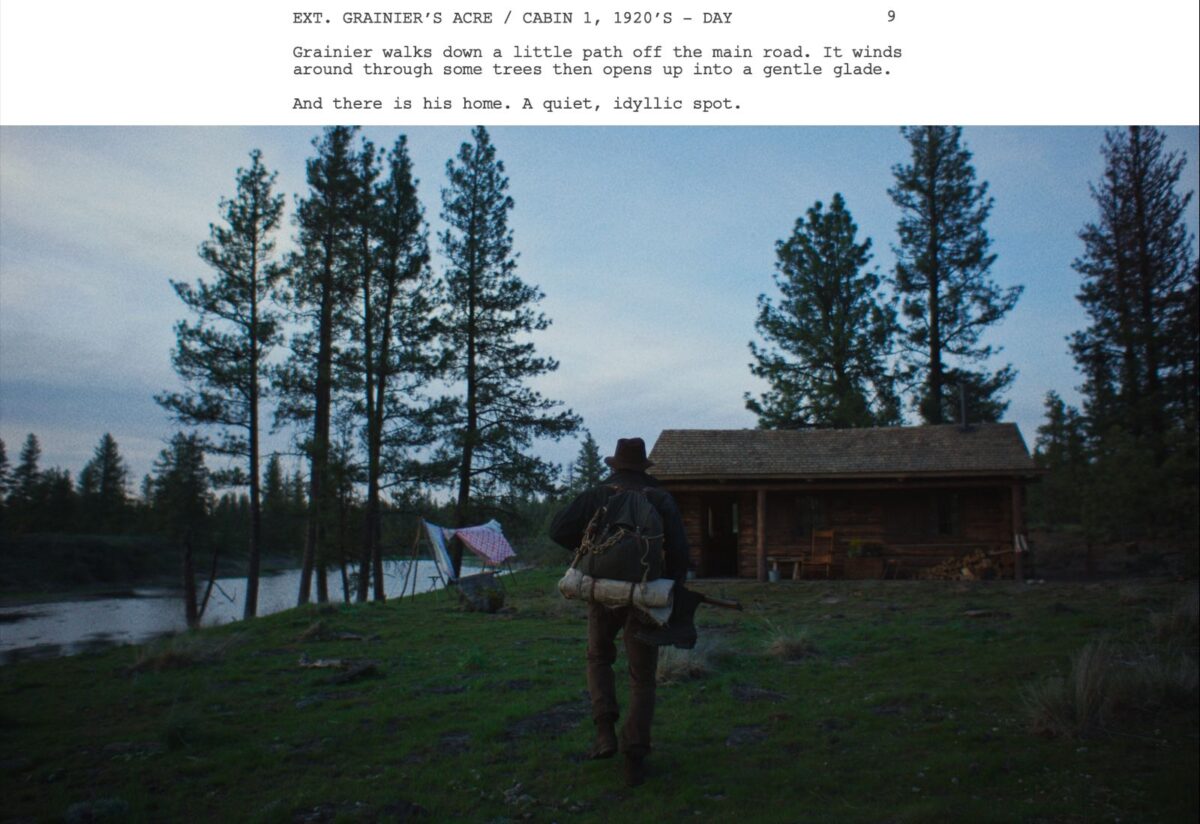

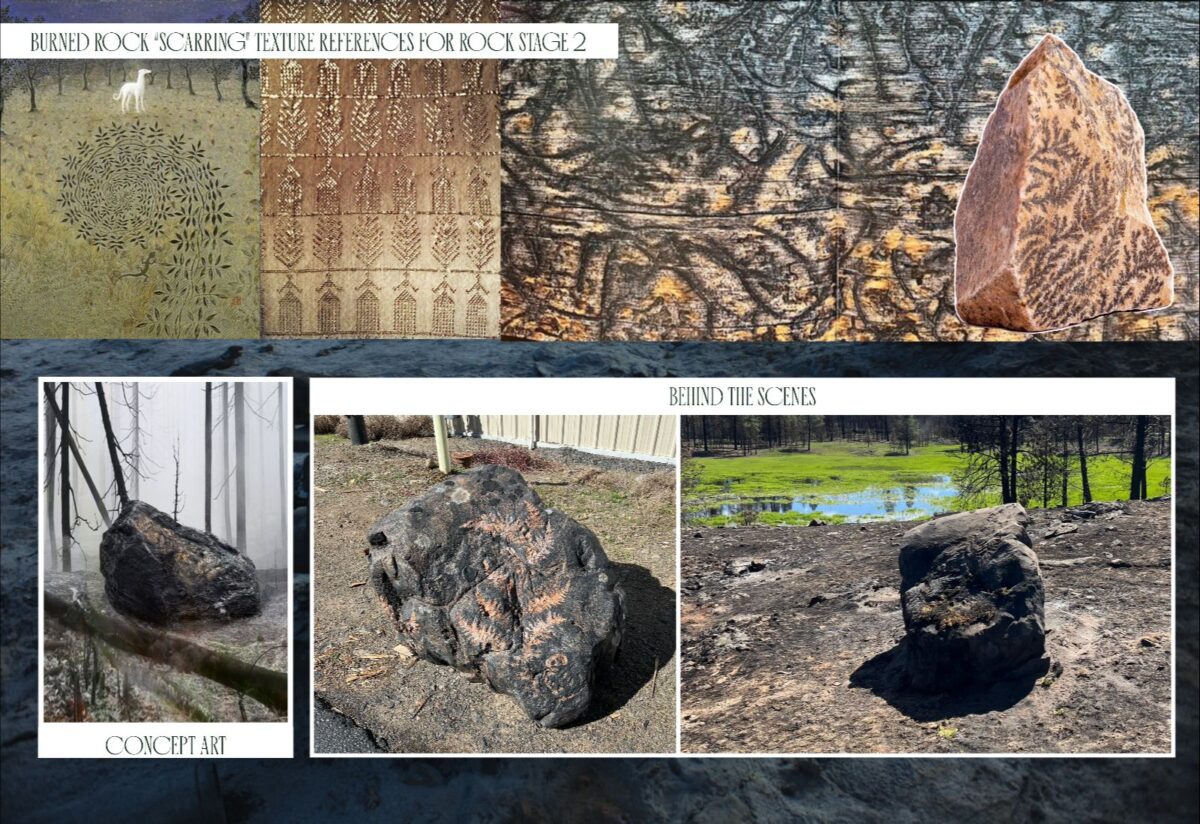

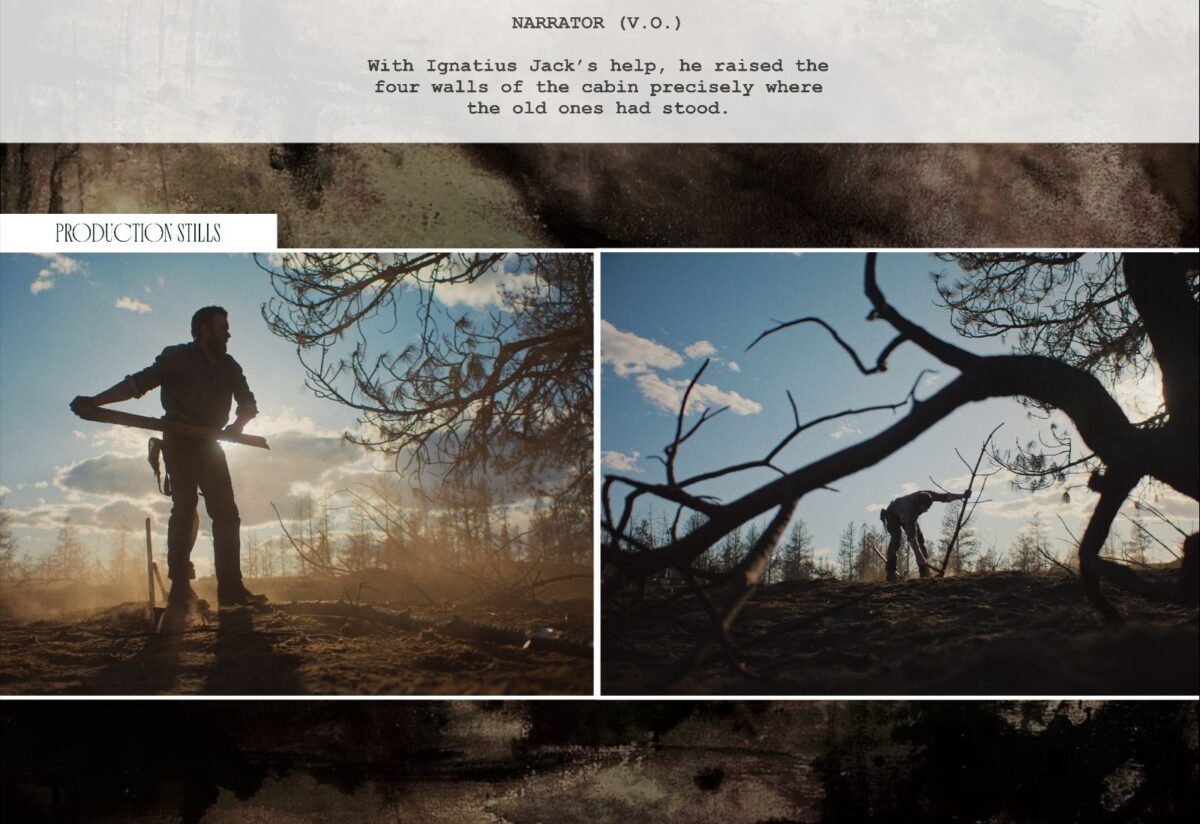

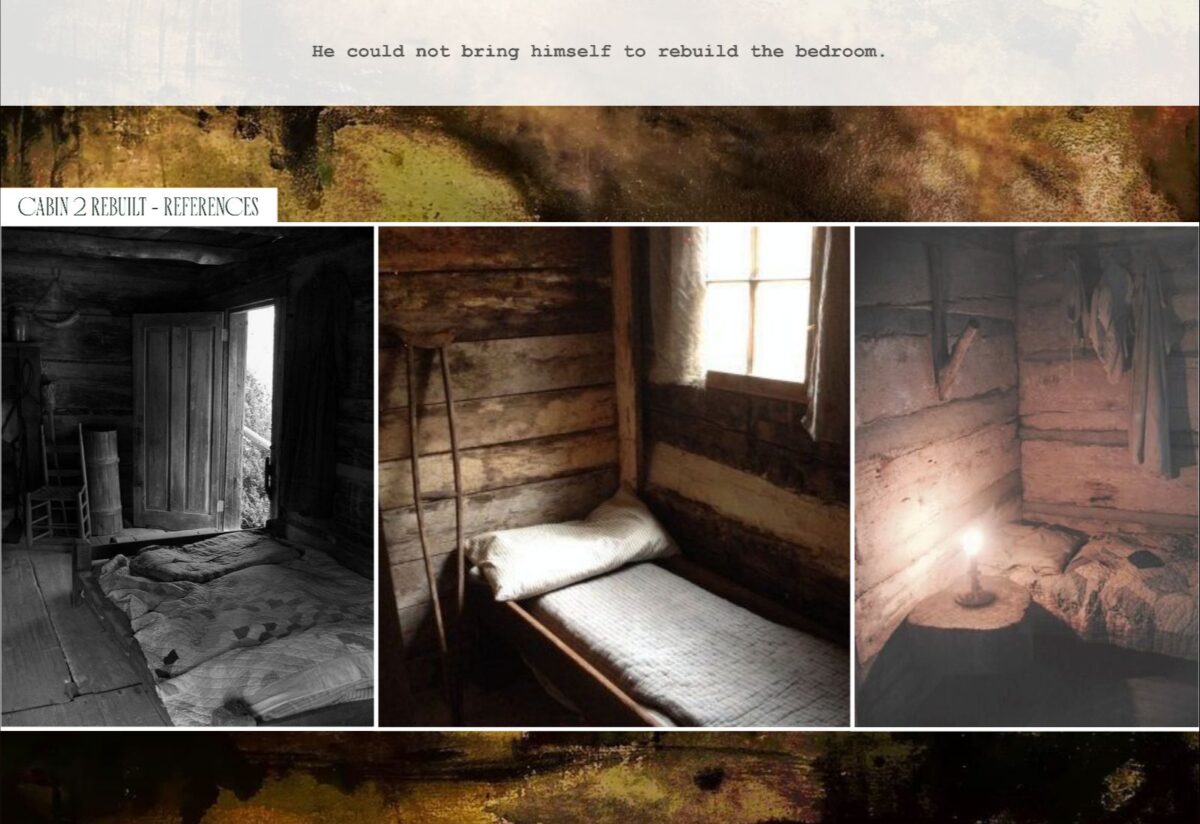

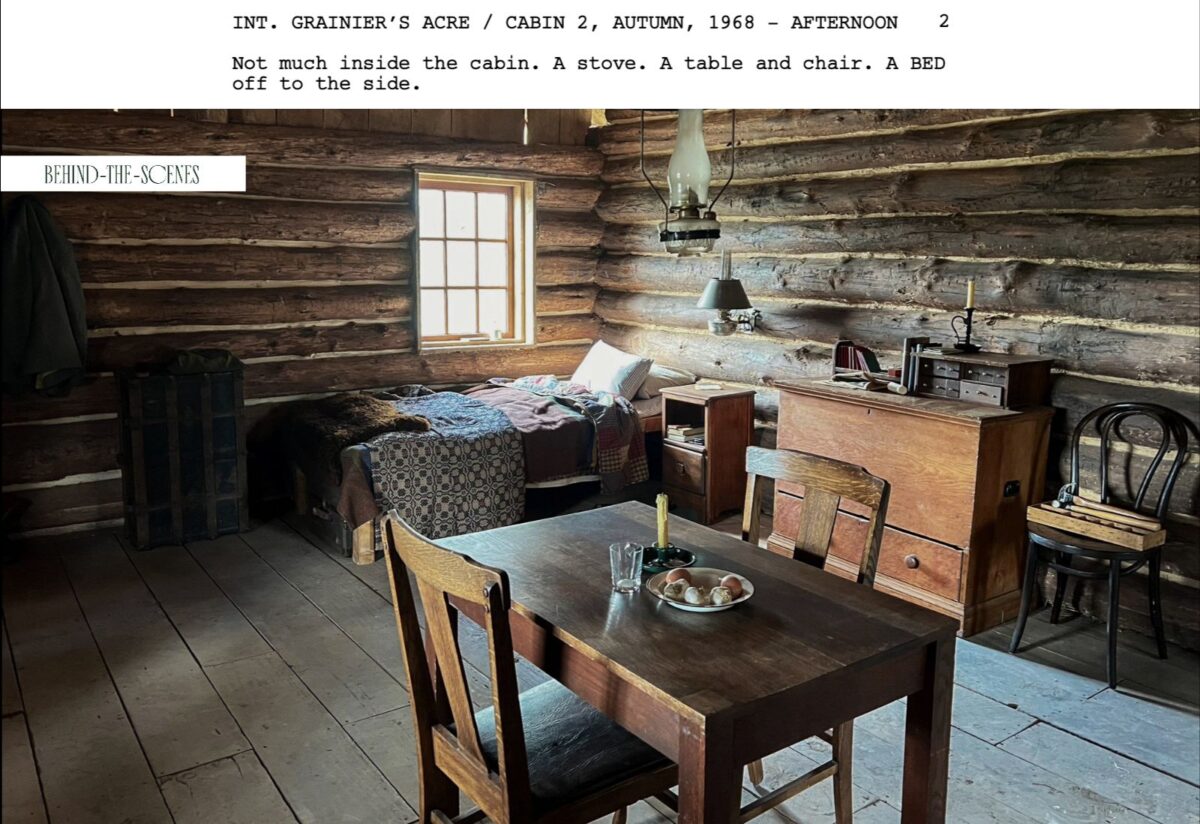

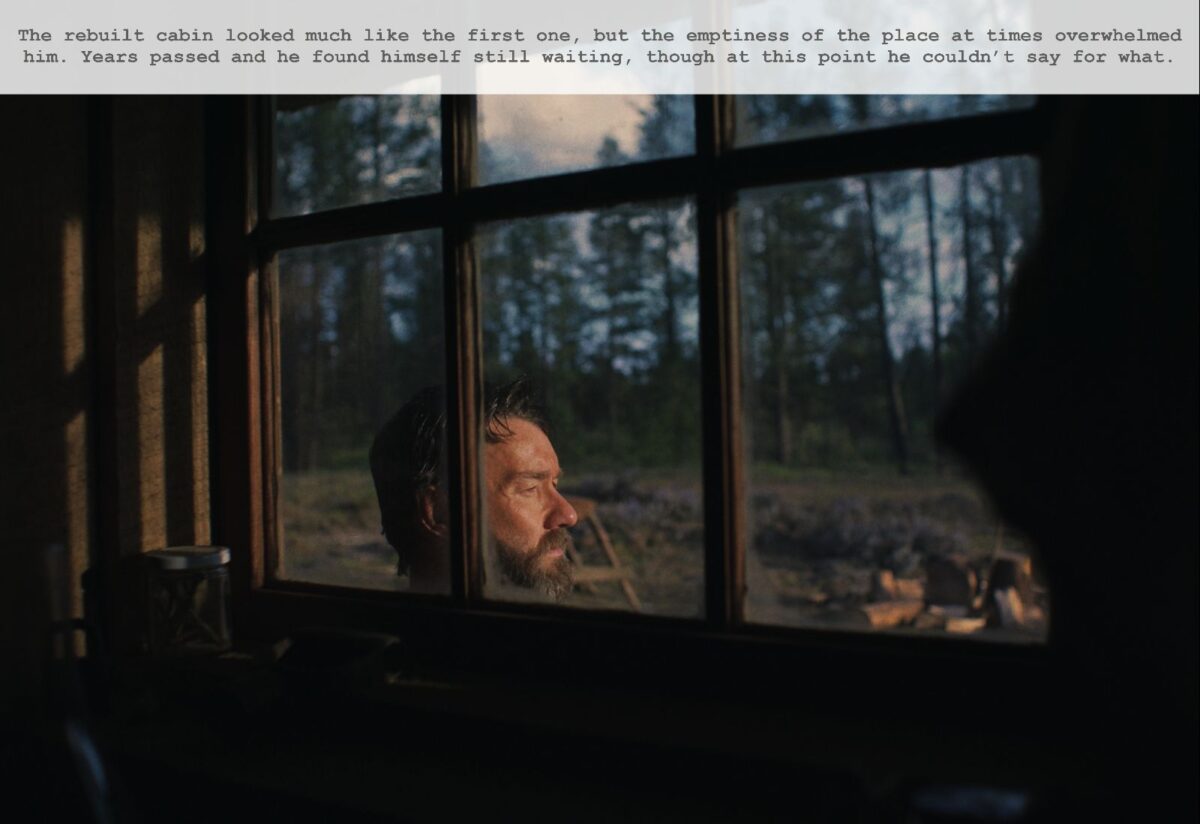

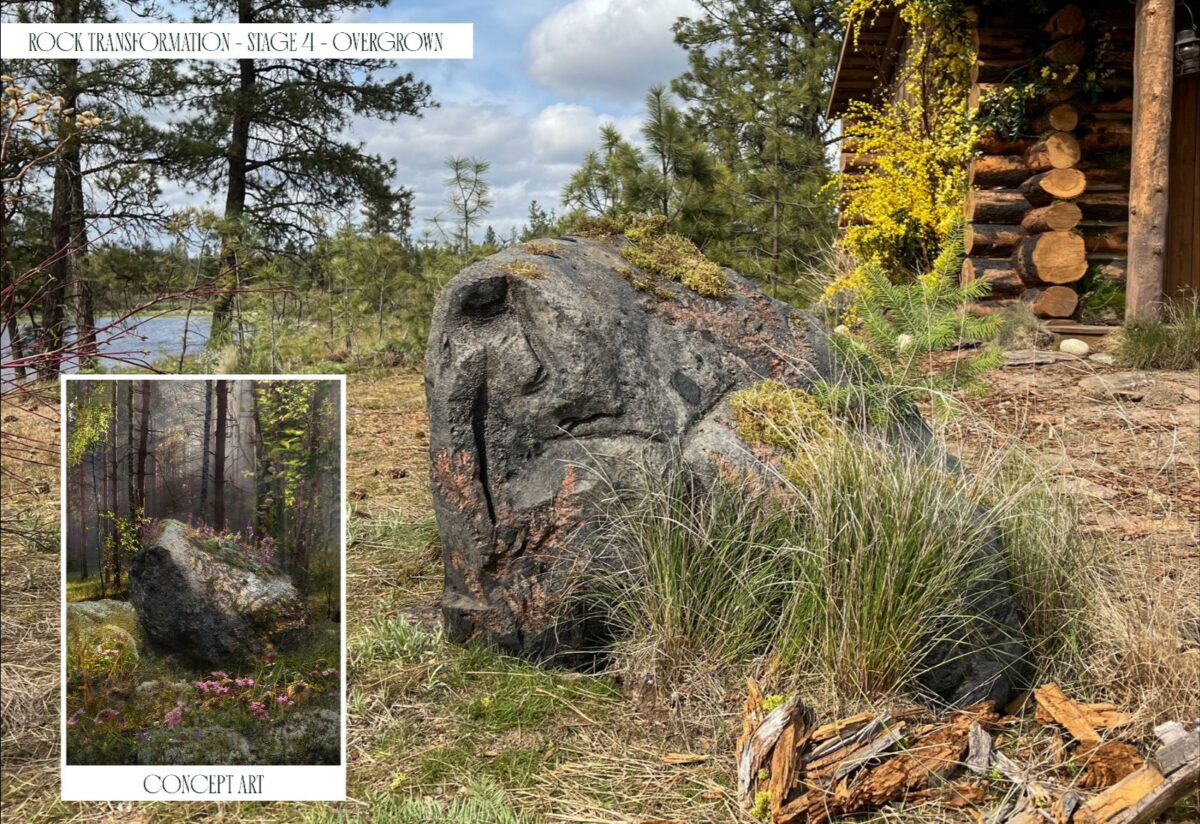

Typically, when you do a small movie, you don’t have ahead of you a cabin build not once but four times. So, a cabin for a family, a cabin that burns down, the ashes of the cabin, a rebuilt cabin, and then a cabin that’s completely overgrown by greenery. And then on top of that, a bridge that you have to make look as though it’s being constructed. And then a train that has to drive over this newly-erected bridge!

The bridge-train thing. Surely that must have been impossible.

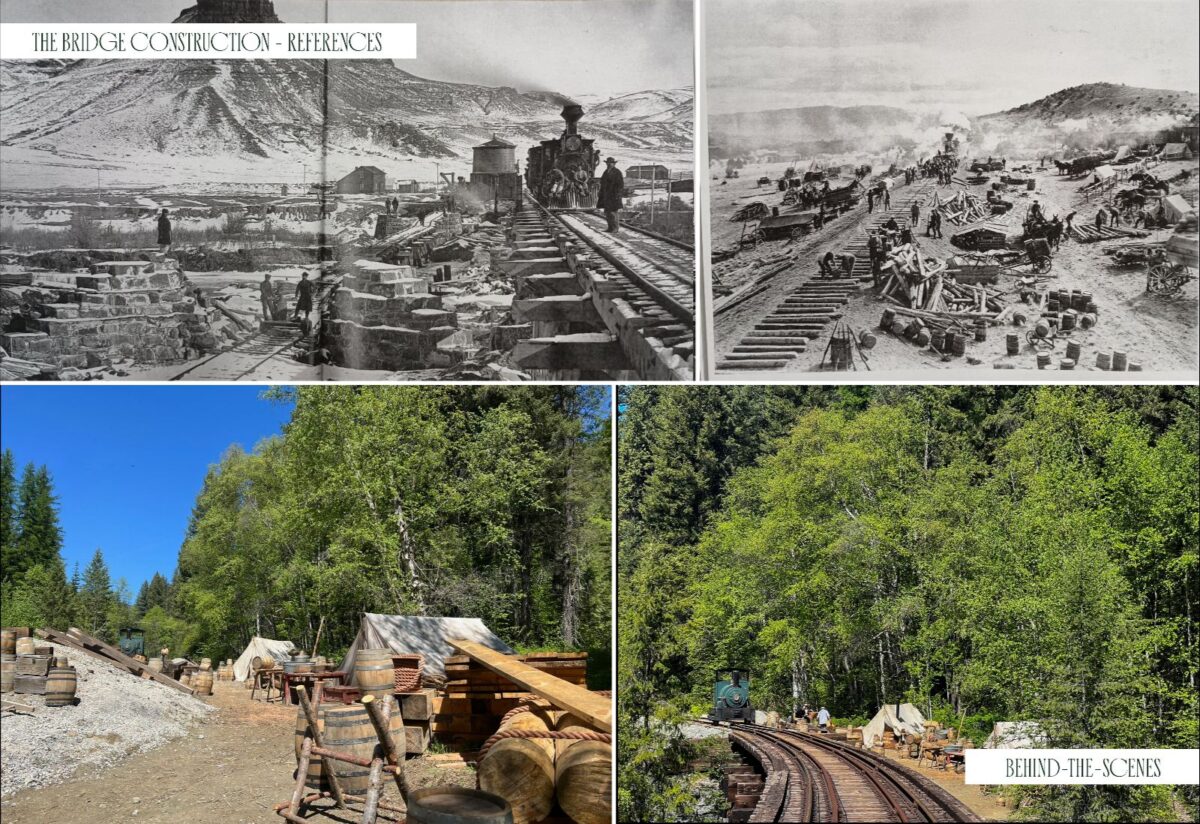

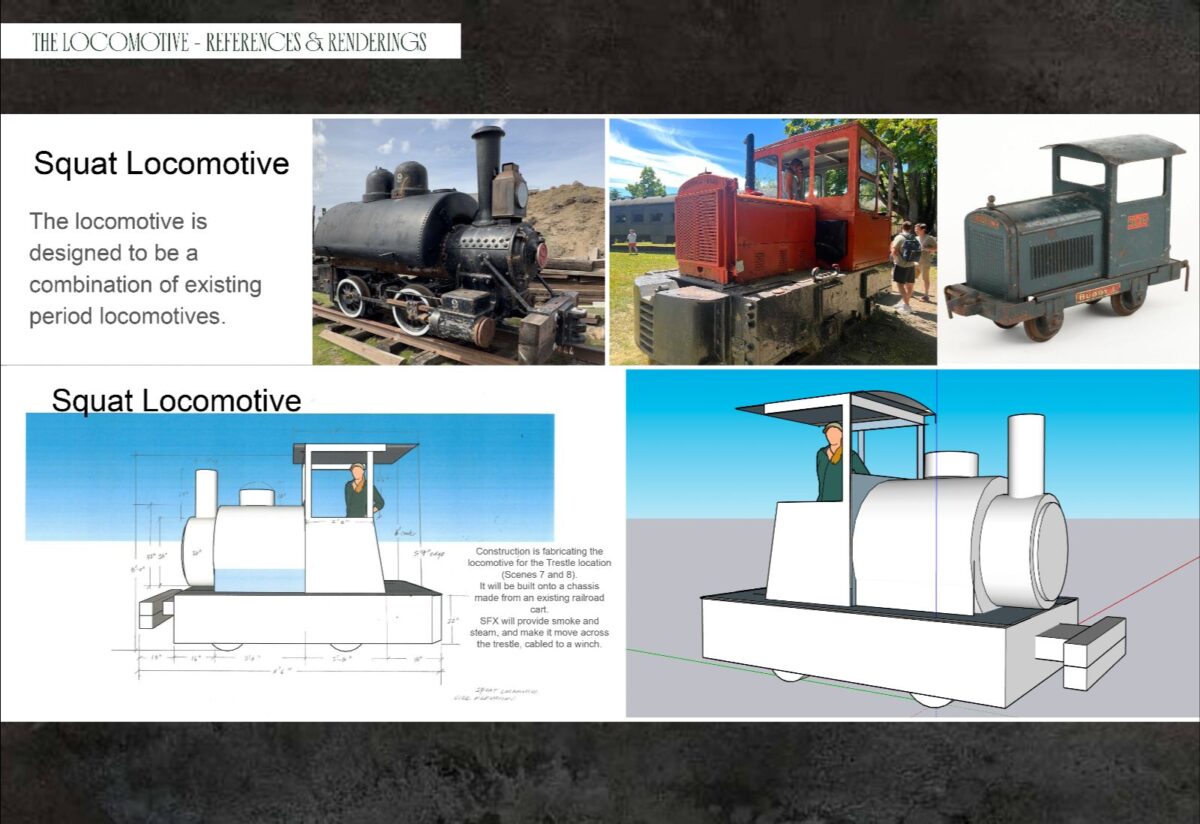

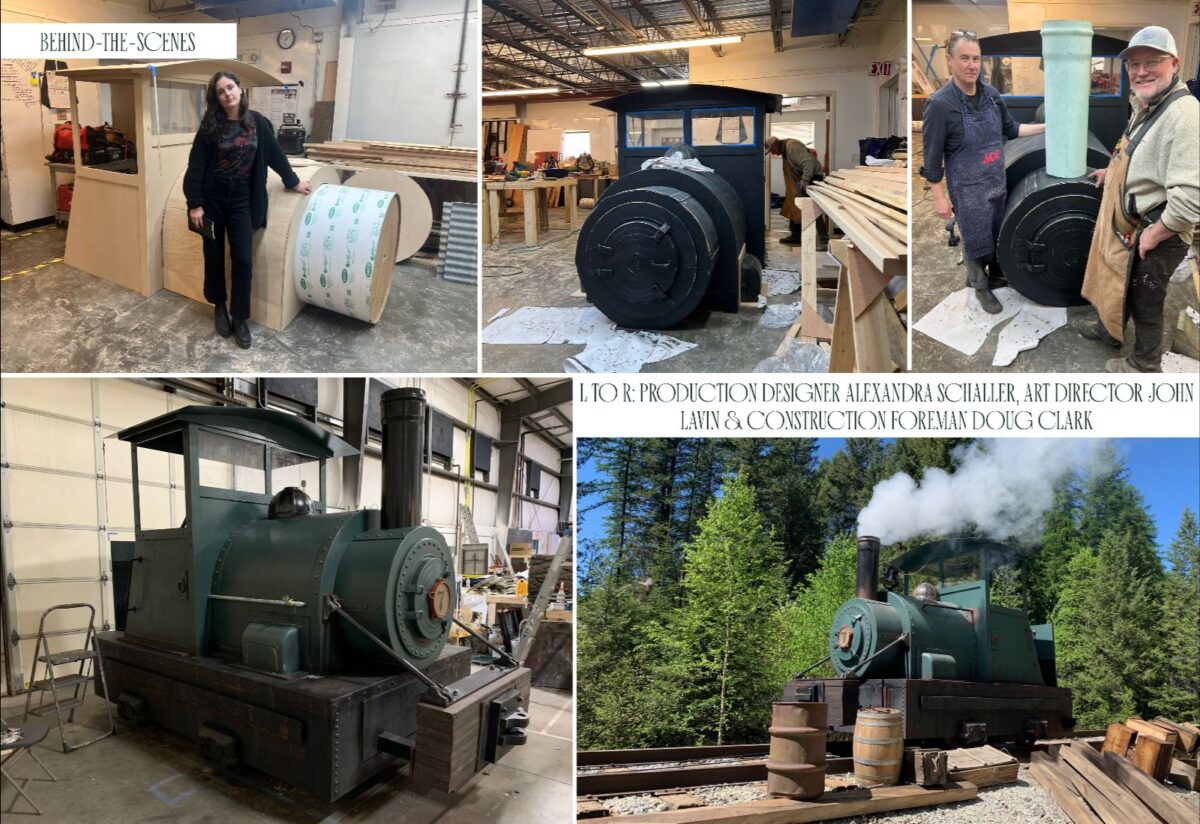

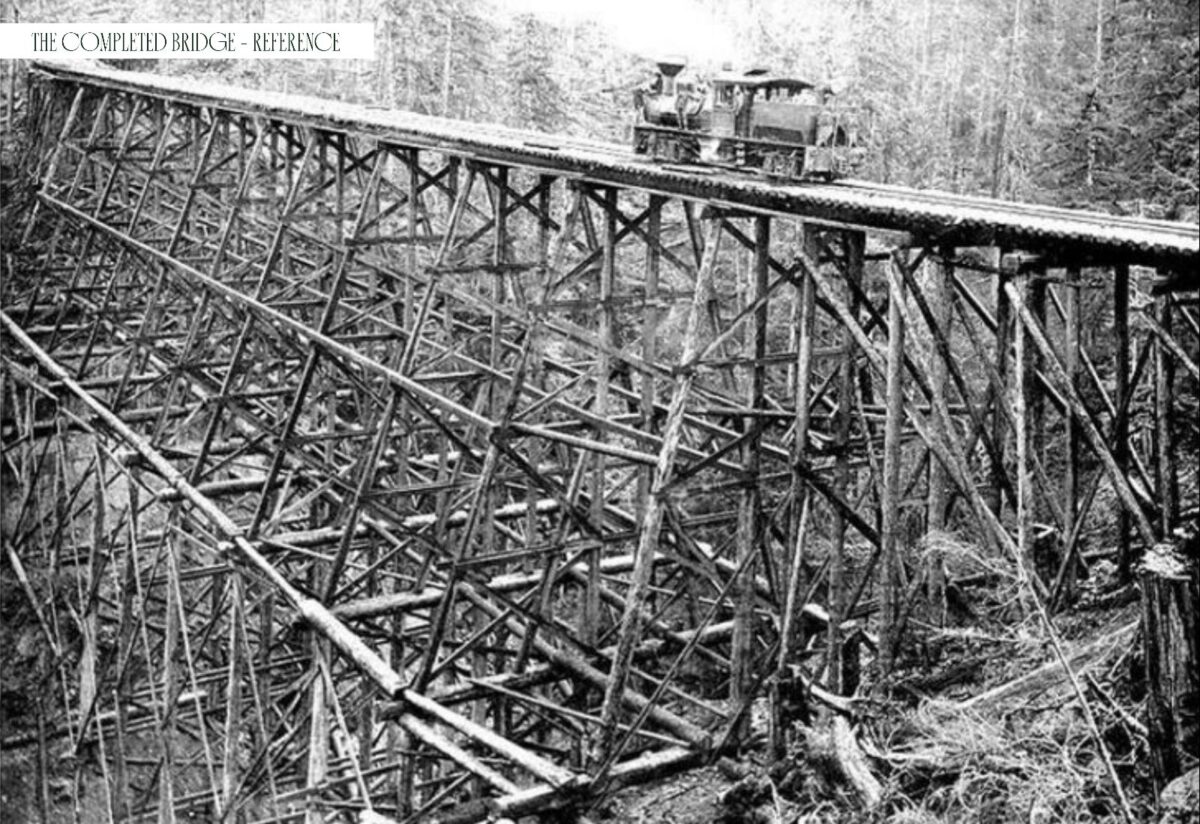

We were originally going… I don’t know what we were going to do. Our coordinator had an excavator called Butch, and Butch said, “Hey, I know of a piece of property up by the Canadian border in Washington where there is this bridge, and maybe go look at it. Maybe there’s something to be done there.” And so we found sort of a relic of an old bridge that was actually constructed with logs, because that was really important. It was very important throughout the movie and throughout all of the production design… to see the life cycle of a tree in the forest throughout the movie. But we had to make this bridge that was now some old dilapidated bridge appear as though it was being constructed. And so we had to set up a big logging operation. The railroad construction, a locomotive that can drive across…[we soon realized logistically] we had to build it. So we did that. We built it.

So that collaboration of the production design team with the location team, that seems like for a movie like this, beyond essential. Were you collaborating with the location team from the beginning of just like what you needed and what could be discovered all throughout Washington?

Yeah, that was a huge, huge conversation. And on top of that, because Adolpho and Clint wanted to shoot using natural light, the positioning of how we built the sets on each of these plots of land was also very, very specific, because we had to think about the arc of the sun and all of that stuff. The location scouting process was really important. The movie started and stopped a few times before we went and made it for real. A couple of things happened and then the strike happened. And, so I had actually had the good fortune of being there scouting before we actually went to prep the movie for real. And so that was really helpful. And then it was me and Clint and Adolpho and the producers just tramping around trying to find the right locations.

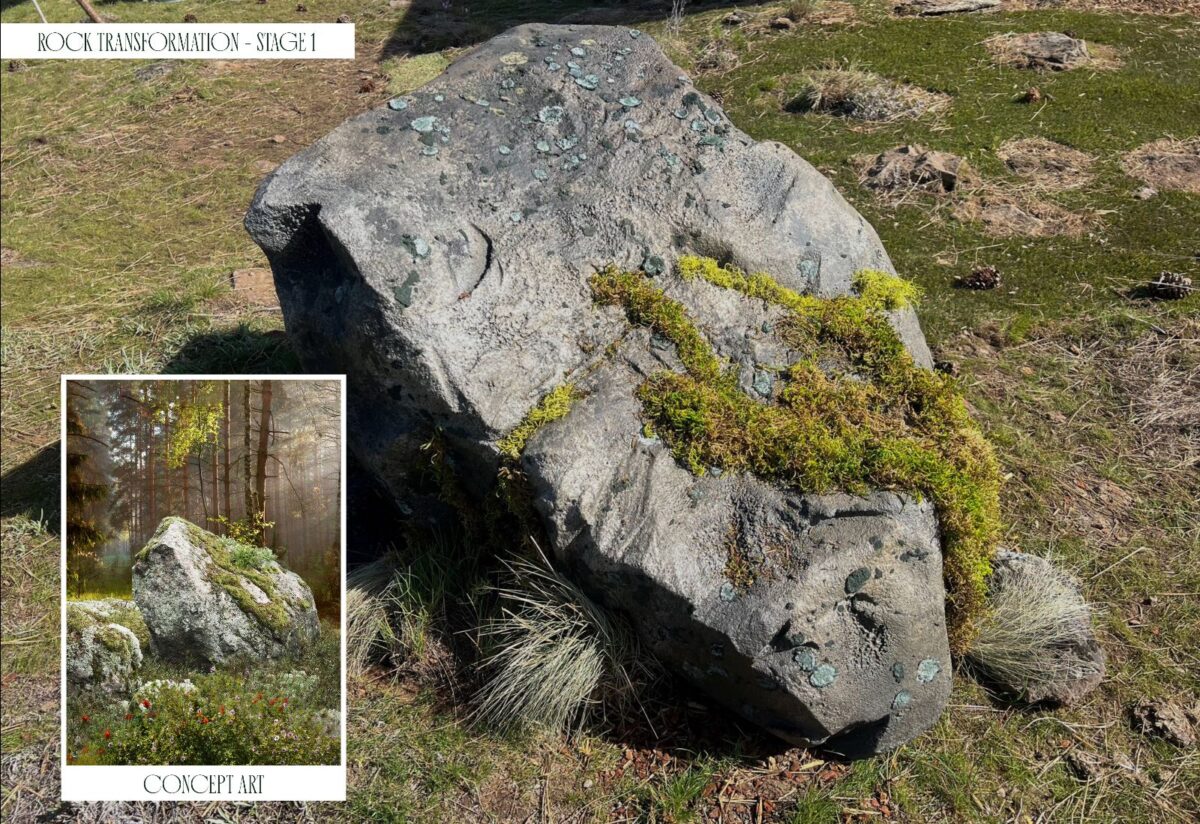

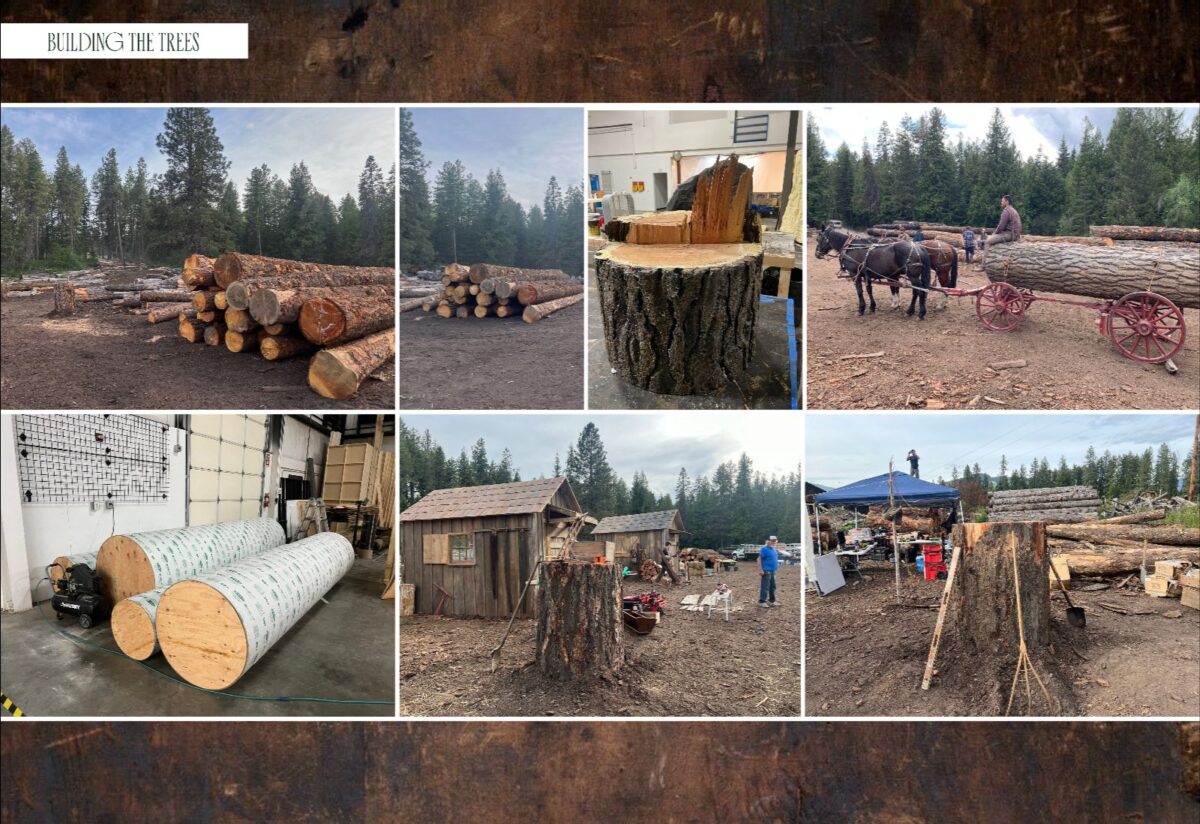

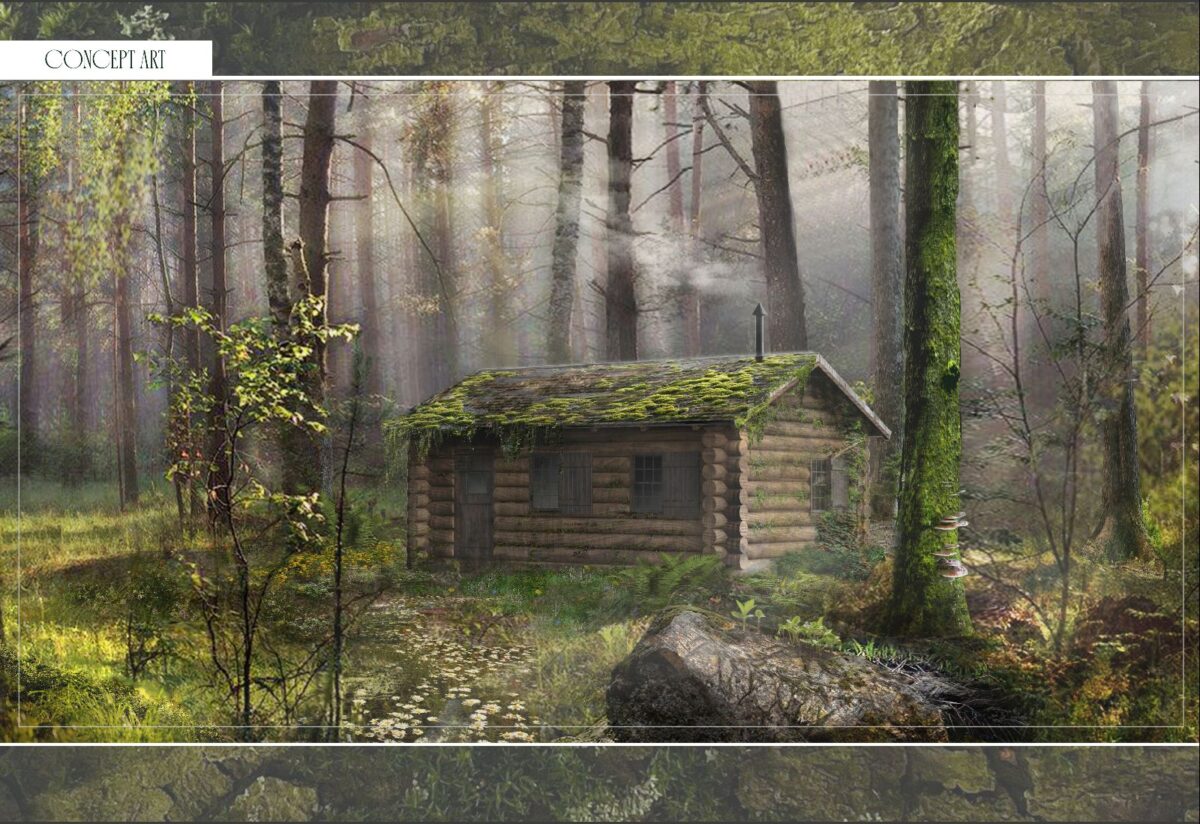

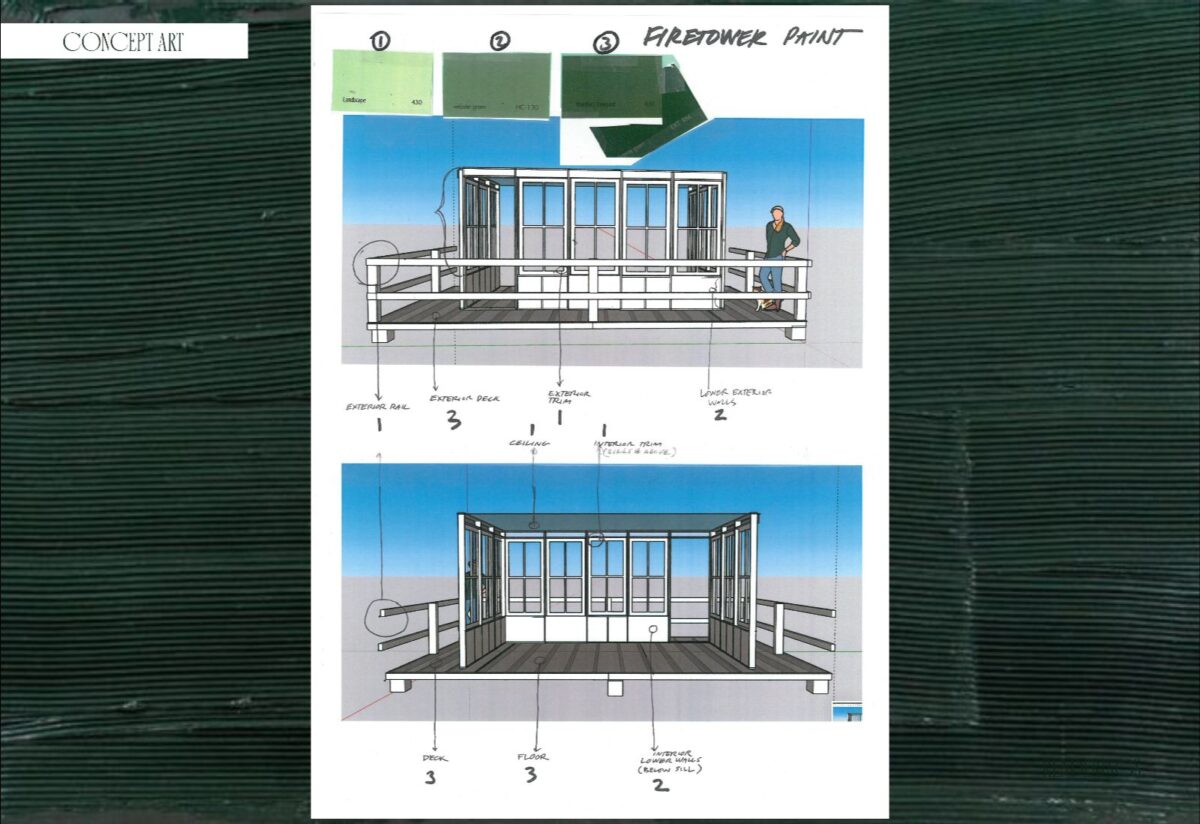

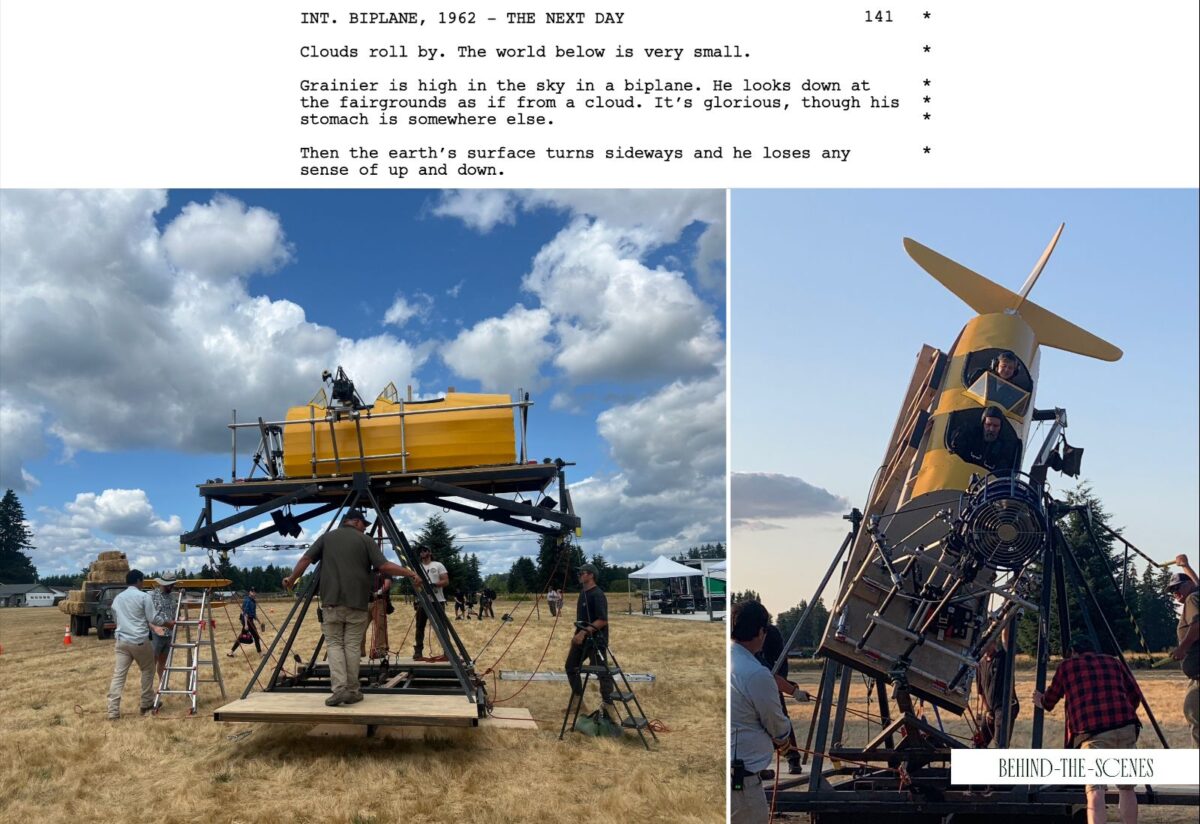

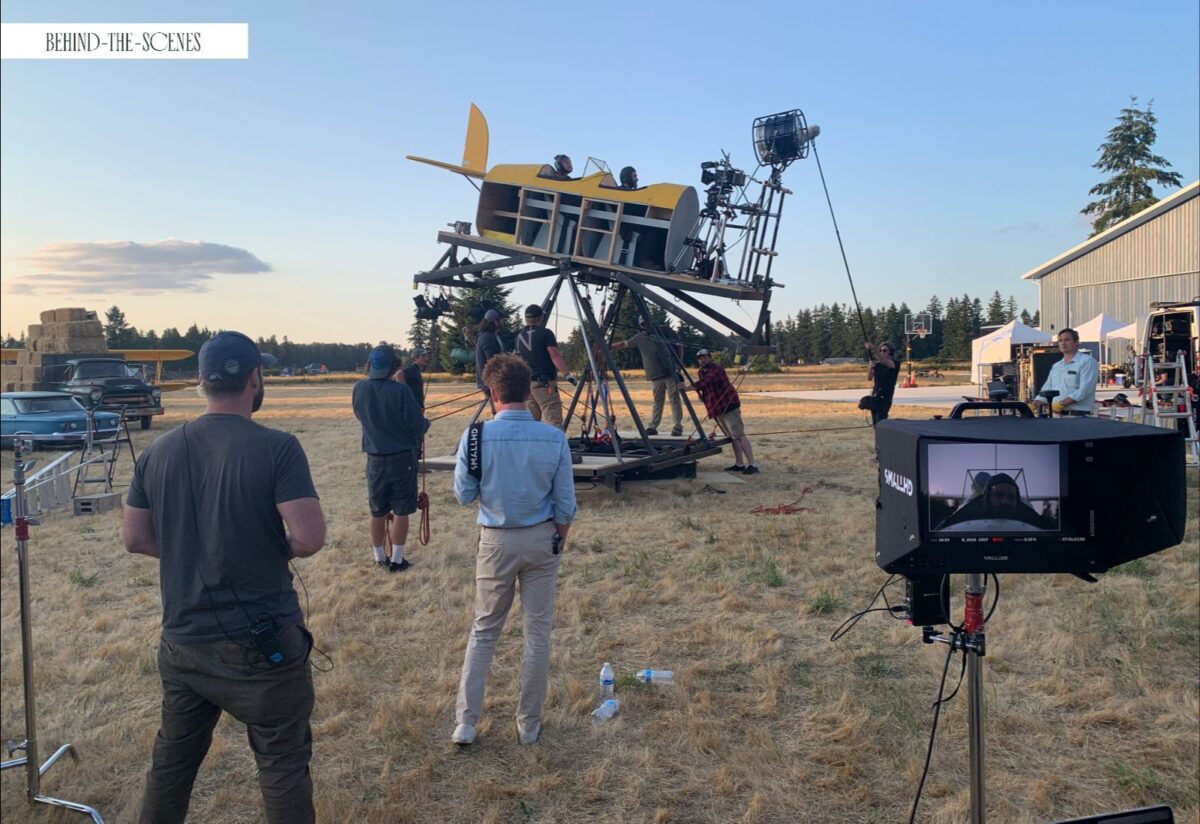

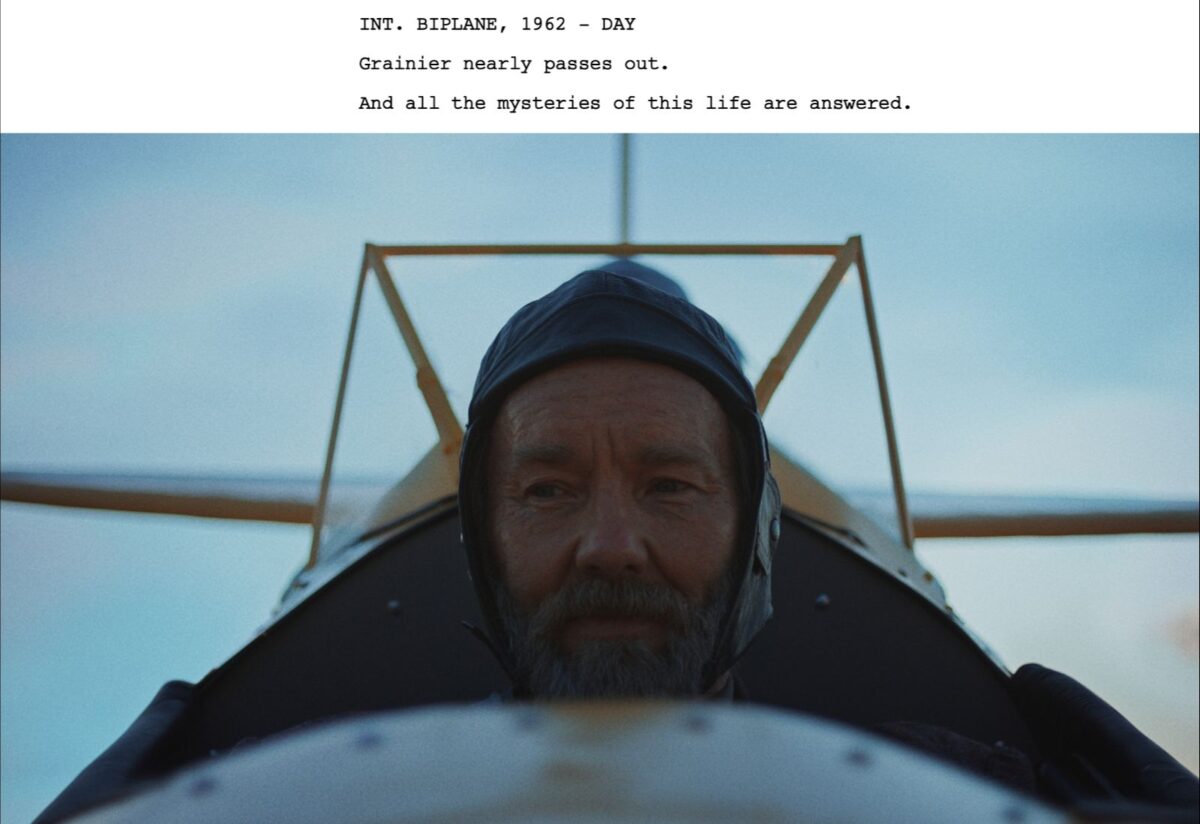

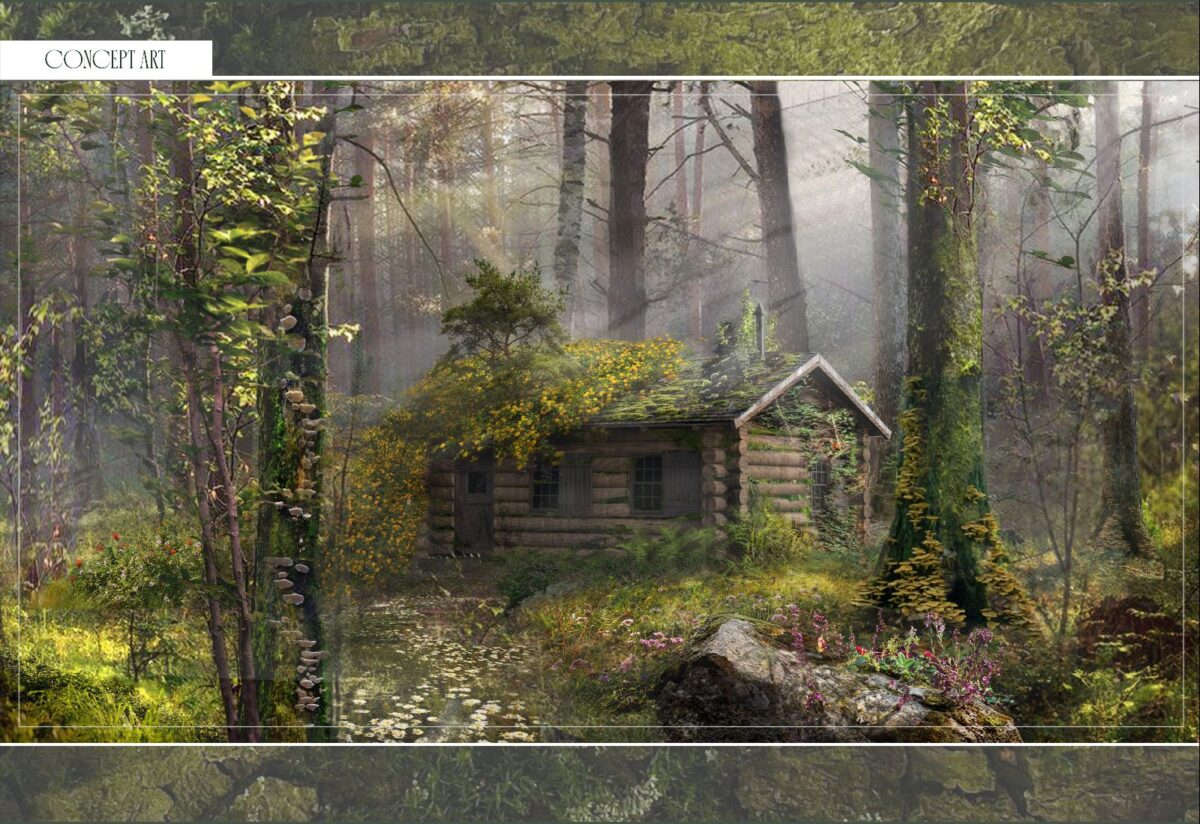

We were up against the wire with the cabin spot, because we wanted it to feel really magical and special, because we’re there so much during the movie. The plot of land in that cabin holds so much significance for the character and his memories. And so it really had to be right. And we waited until the absolute last minute and we found it right in the nick of time. But in terms of other things that we built, this movie was really nuts, because if you think about it, right, we’re documenting a time, right? The early 20th century, when loggers are building America, and the towns and the railroad, and cutting down these old growth trees. And so we had to build a lot of those really big 12-foot diameter cross-trees that you see were built. Also, because we needed so many downed logs. And a lot of those were real, but we needed to, for production, move them around. And a person can’t move a log around. And so we had to sculpt a lot of them out of foam. So that was a pretty crazy thing that I didn’t think about when I first read the script. But it makes total sense when you think about it. Then on top of that, if that wasn’t enough, we had to build a fire tower. We had to build a plane for Joel in the final scene of the movie, because we couldn’t put the actor up in a plane for all those reaction shots. So we had to build it! It was truly remarkable what we had to do on such a modest budget.

With the plane, the practical way with which you captured that flight, what I love is how it seems like there are so many old tricks and new tricks combined. There’s modest volume stage usage [which you mentioned] but then so much of it is finding the right place that exists and literally building the cabin. It’s a beautiful synergy of old and new, which is also kind of what the movie is a little bit about, which I think is nice.

Yeah, it’s true. It’s a nice way of thinking about it. And, yeah, it’s like, okay, well, the plane sequence that we were referencing was one from a Christopher Nolan film. And we were like, “Okay, but that is a $100 million movie. How are we going to pull off this Nolan-esque plane sequence on our budget?” We built the body of the fuselage on a gimbal.

A fairly famous story about Nolan with Oppenheimer. He cut down his shooting days significantly because he had a conversation with the production designer and the costume designer and they were basically like, “If you want to build the town, it will take this long and cost this much. And if you want to dress all these people…” And he was like, “Okay, I want that money to go here. So I will figure out a way to cut down my shot list.” It’s obviously at a smaller scale [with Train Dreams] but it sounds like you talked to Adolpho and Clint about [something similar]. If everybody does collaborate, you can get what Train Dreams is.

I’ve been reading the novel and at the beginning of the book there’s a beautiful line where [Johnson] writes that: “Robert was wondering at himself.” The whole movie is kind of him doing that… it’s such a beautiful adaptation. Did you read the book? Were you worried about reading the book? Did you want to avoid it? How did you approach that, because you’ve worked on other literary adaptations.

In this case, I did read the book, because I just felt like it was important. While Clint was always clear that we were making the script and not the book, it was very important to him to maintain the essence of the book. And so I read it. What is so powerful about the novella is that there’s this dreamlike undercurrent woven through the entire narrative, which was also present in Clint and Greg [Kwedar]’s script. And that was a really nice parallel. The movie does deviate from the book in some areas. But I feel like the essence is… he really remained true to its essence.

You’ve done so much good work over your career and you have so much to come, which is exciting. Was there anything comparable? You worked on The Get Down. That must have been insane.

That was insane. Yeah, that was insane. I remember, so I took over The Get Down from the original production designer. And she’s actually the one who chose me to replace her, so it was a great honor. And she said to me, she said, “Listen, everything that you have heard about ‘less is more’ does not apply here. Here, more is more.” And she really wasn’t kidding. The Get Down was my first really big TV show, but my first really big narrative project [as well]. And for a while before that I had been working a lot in commercials, because it was still sort of the tail end of the golden age of commercials. And so I really cut my teeth doing some pretty gigantic campaigns. And I think that if I hadn’t done those crazy big commercials, coming from independent film, I would have been just completely bulldozed by the experience of big TV.

We were talking about Maggie’s Plan, which is now a long time ago. [Directed by] Rebecca Miller, underrated filmmaker, so talented. She just did the Scorsese doc that’s out now. That’s New York, speaking of locations, right? That’s a [location-first shoot], right? Parts of New York City that anybody who lived there would recognize.

Yeah. It was a relatively small-budget movie. But at the time, in my career, it was my first union movie, and then working with such a filmmaker as Rebecca Miller. I was a little starstruck. And she has such a presence and she’s such a leader. I like working with people I admire, because it really pushes me to do my best work. It was a location-based movie, but surprisingly, I feel like we’ve all seen these old New York movies with these tiny New York apartments that are crammed full of stuff and full of books. And we’re scouting, scouting, scouting. Not one single apartment that’s full of books can we find. Not one. And so it was a sort of ground-up thing. We only had a couple of set builds on that movie, but we basically transformed all of the locations that we found, because we couldn’t find anything that was just right.

That stuff is just “tales as old as time” right? You have that conversation with your location scout and you’re like, “Well, surely we’ll find the bar that has the thing.” And then you realize that it maybe just never existed, right? It existed in the movie, but it was a set, right?

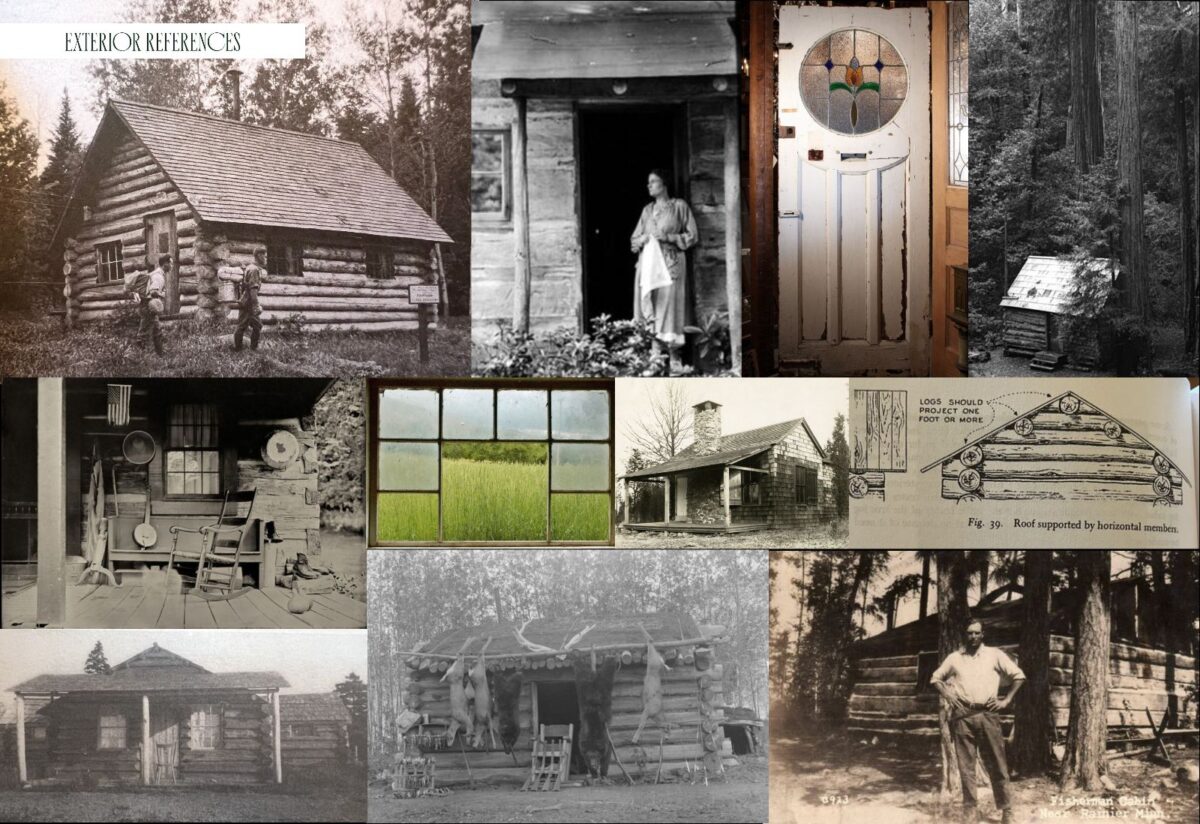

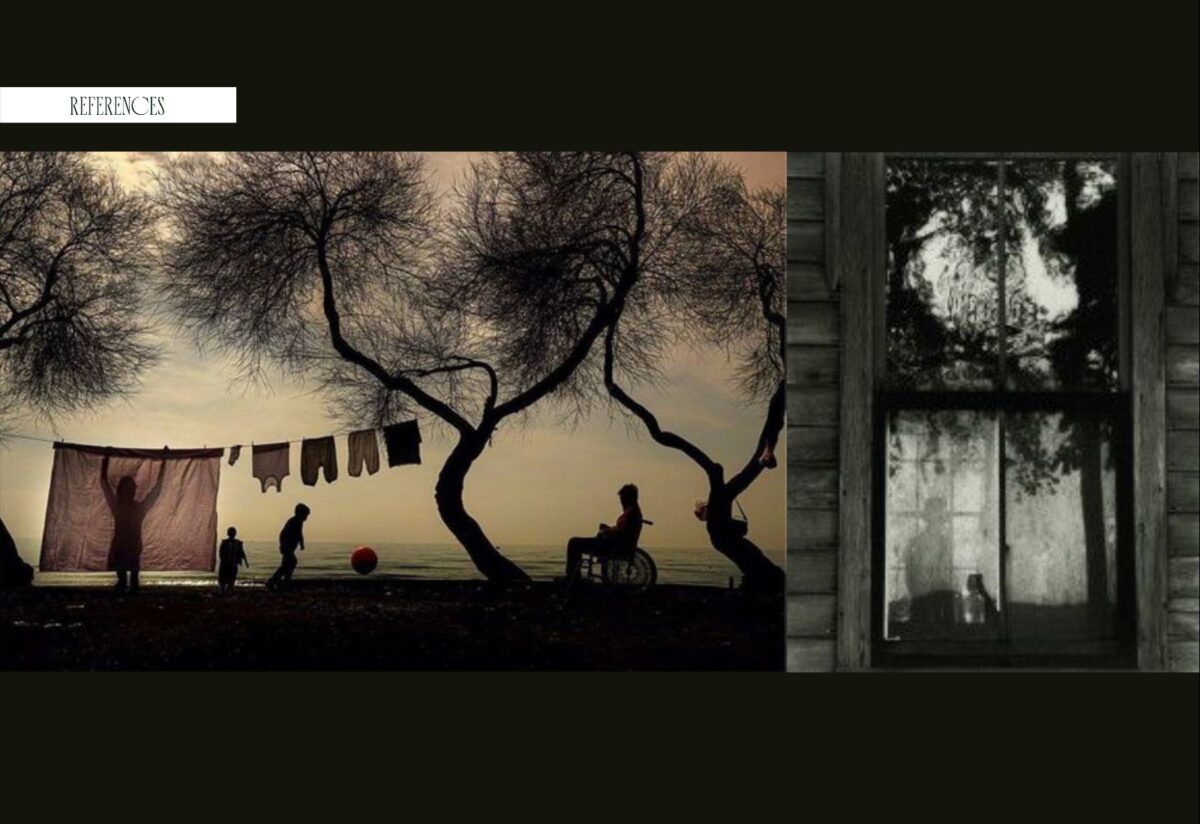

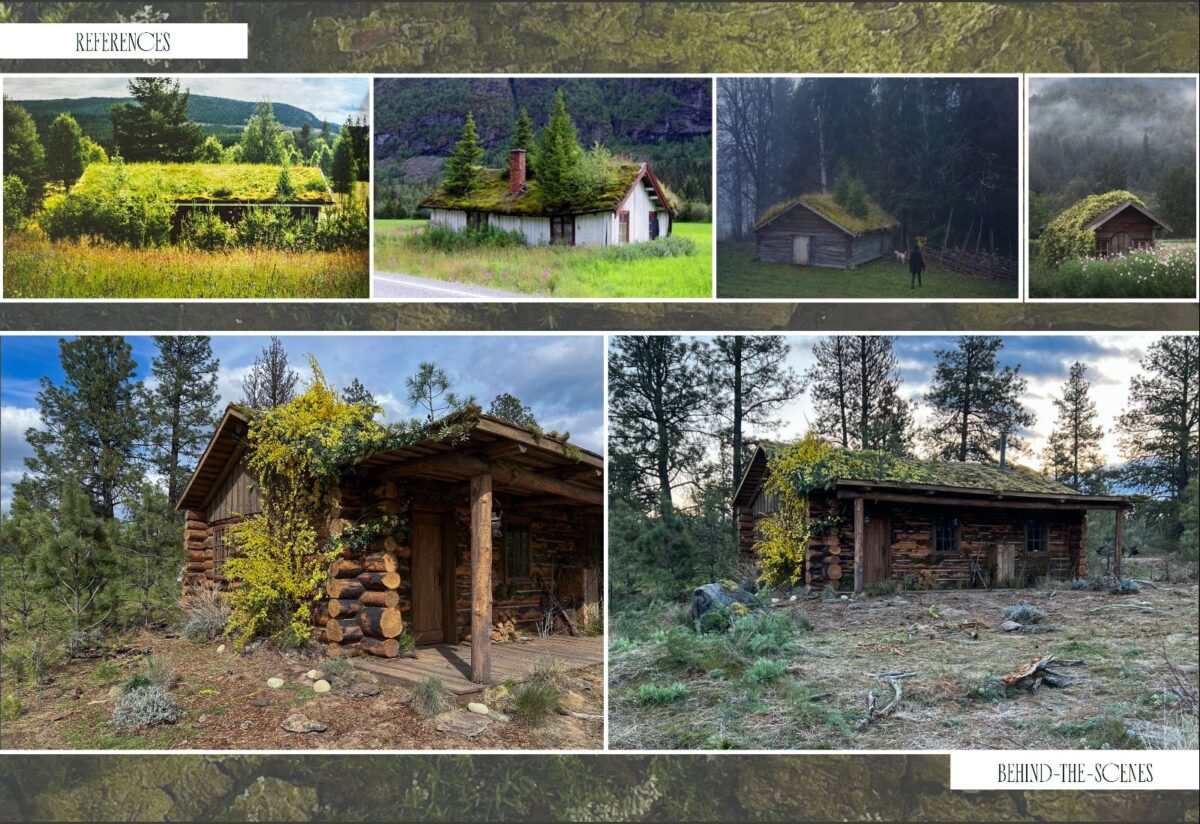

Exactly! I was just doing a talk with Hunter College film class and I had shared the presentation with them, and they were looking at my mood boards, because the professor was having them actually make mood boards as part of their class. And one of them said, “Oh, I noticed how you don’t have any movie references in your mood boards.” And I was like, “Well, it’s not that I don’t. It’s just that’s not the first place that I look, because if you think about it, the movie is a piece of work. It’s an artwork, right? It’s not the truth, right? It’s the truth for that particular film, and it’s not sort of research. It’s inspiration.”

That sounds obvious, but it’s [a great point]. Movies are not reality. I always say this on our podcast. Movies are time machines. Maggie’s Plan, for example, is ten years old. I lived in New York back then. If I watched it again now, it would be a time machine. I would remember where I lived. I would think about where they filmed. And that’s why I love old movies so much and a movie like Train Dreams, which is a period piece, you’re getting both at the same time. You’re getting this kind of rendering of what this early 1900s must have been like but lensed [and produced] in this modern way. Maybe the lenses are old, but the machines are new, right? You’re capturing stuff with new techniques, so there is a newness to it. And you can’t rely on that being a reference point necessarily.

And even if I did find the apartment full of books that was the perfect apartment full of books, I probably would have had to remove all the books, because exactly where the books were is probably where the cinematographer would want to put the camera. So it’s probably easier to make it to suit the film.

Was there a specific time period or thing you’re referencing for Train Dreams?

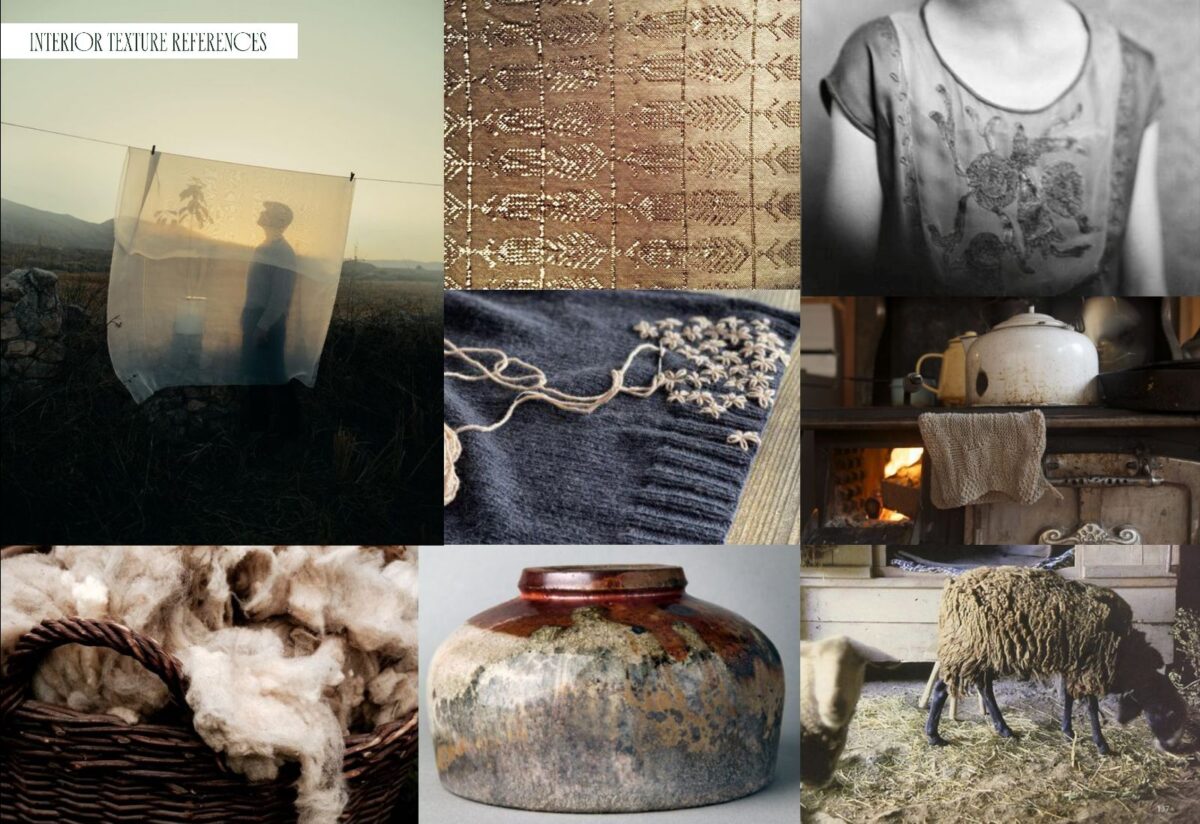

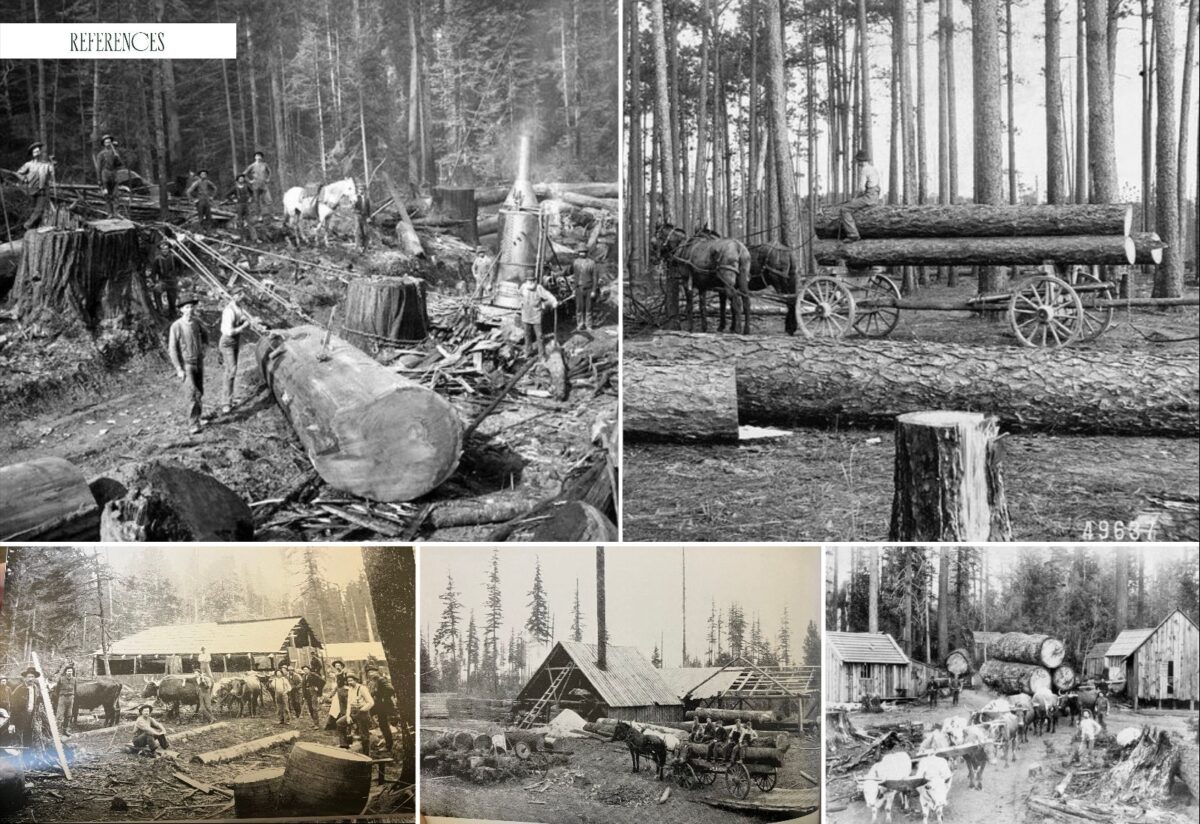

It goes back to the movie that Clint wanted to make. And the way that he and Adolpho talked about photographing it. And what we wanted was a documentary-like observation of the world. Therefore, the design of the world had to be fully immersive. My way into the design was, “Okay, well, how do we want it to feel?” And we talk about color palette and texture. But also, in order to really convince the audience that we’re in a place in time, I wanted to do my research from the time. The movie goes from the late 1800s to the 1960s, and it’s a very dreamlike movie. We needed to figure out how we were going to tell the audience that time was passing without having that kind of museum diorama feeling like, “Hello! We’re now we are in the 1960s!” And so I wanted to learn all the details, and I wanted to learn about how things were built, and the men who built America, and how you would build a log cabin back then, and apply those methods to the movie as the foundation and build on it from there.

Yeah. I mean, it really comes through. Another movie that you worked on that is a movie I love so much is After Yang… I just want to shout that out, because it’s so good.

I love that movie.

It’s funny because it’s so different than Train Dreams, but in a way––and this is kind of what I’m asking––was there another project you worked on that prepared you specifically for Train Dreams, or was it kind of all of it together?

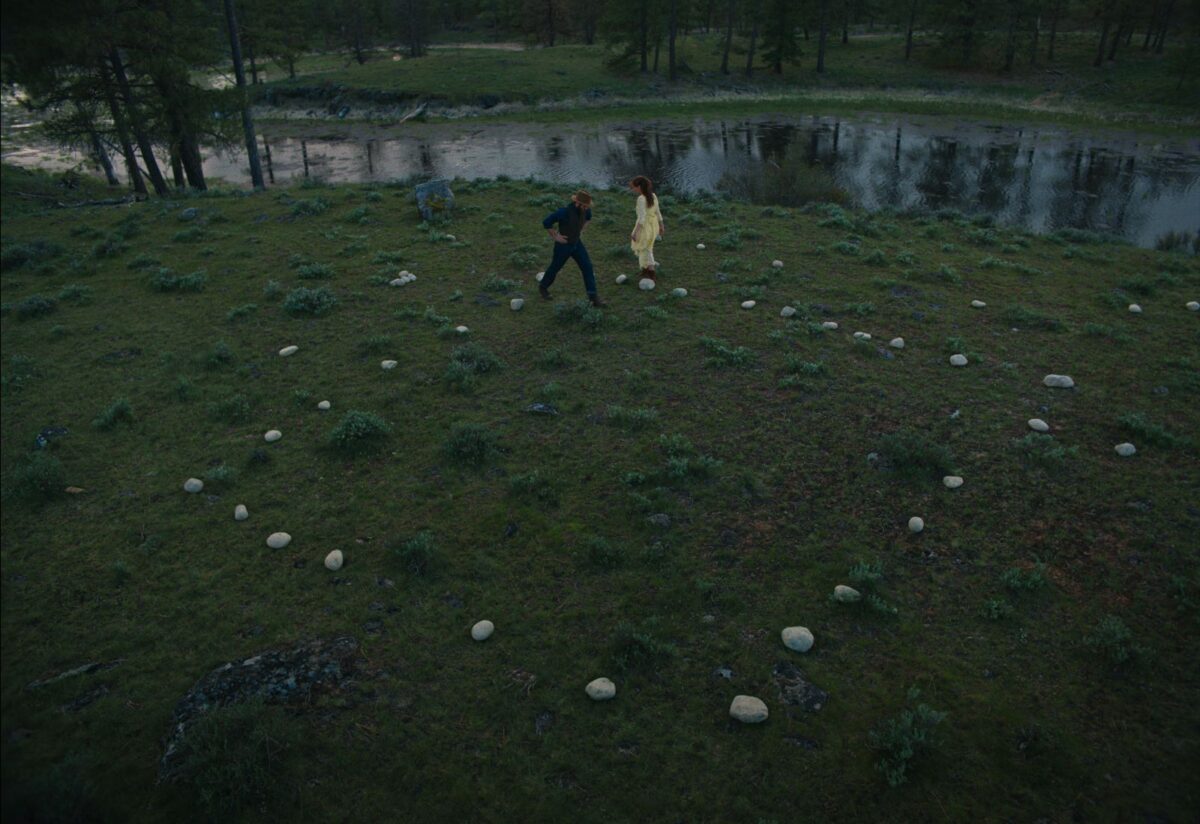

The short answer is all of it together. I think that Train Dreams is a very ambitious movie for the budget, and had I not had the experience that I’ve accumulated over the years about knowing how to do things, it would have been a different story. On a creative level, I would say that everything comes back to my background in theater and sculpture and installation art and immersive theater. I went to art school in London, where I grew up, and then I moved to New York with an English theater company called Punchdrunk to work on a show that was in New York for many years called Sleep No More. For those who don’t know, it’s an immersive performance, told through dance of Macbeth. It’s set over six floors in a warehouse in Chelsea, in New York. The audience is free to roam around the space. And if you catch the actors, you can follow their narrative, or you’re free to wander. Either way, the audience is transported to a place. And that is the quality that I like to bring to the design of the films that I work on. I want it to be transportive. I want it to be fully immersive. I want it to be as detailed as possible. And for Train Dreams, and for the way that Adolpho and Clint wanted to shoot it, they wanted to be able to follow the actors relatively freely. They wanted 360-degree shooting ability, which is really hard to achieve on any budget, but especially on a small budget, especially on a period movie. Right? Because if you look over here, then you’re in 2025. So everything has to be really curated. But I think it’s that sort of approach to immersive theater design that was really the foundation for my being able to do this film so many years later.

Do you have a dream project? A dream thing to design or construct? Is there any ambition of like, “Oh, that would be cool to try to tackle?”

Oh, my gosh, there’s so much that I haven’t done. But I would say it’s less about the set, really. Because while I love the set and the look of the set, I’m really interested in sort of the set as part of the whole, you know, the overall story that we’re telling. And I feel so lucky, going back to Rebecca Miller or Ira Sachs or Baz Luhrmann or Kogonada, or Clint Bentley, the common thread among those directors is that they’re all storytellers. And they’re not just making images for the sake of imagery. They have something to say. And the essence of that is what’s interesting to me.

You mentioned Ira Sachs and [his film] Little Men is an example of small, beautiful work. And Ira’s new movie, Peter Hujar’s Day, is set in one apartment. And to your point, it’s such an interesting [example] of camera choice, location, and production design. Little Men is like that too. There are these parts of New York that you’re just kind of discovering. Bringing it back to Train Dreams, it’s already had a [considerable amount of critical] success as we record. Has there been a highlight to the reception? Has this process been new? Has there been a movie [you’ve worked on] that has gotten this type of attention? Maybe After Yang?

I absolutely love After Yang. I mean, that was a very, very difficult movie to make. I mean, firstly, where to make it.

Where’d you make it?

We shot in New York, and it didn’t look like New York. And it’s supposed to be at some indeterminate time in the near future. And what people don’t realize is that the future is also a period, right? Except it’s a period that doesn’t exist, and so you need to make up the rules of what that period is. I had a lot of fun on that movie. And I think that my favorite projects I’ve worked on are the ones where the creative collaboration has been extremely close. Like, I saw the costume designer of After Yang (Arjun Bhasin) last night. You know, we love each other. We love working together. I think when the creative collaborations are fulfilling, it really helps the project to sing. I think you can just feel it. And After Yang is one of those movies where there was, again, a real connection between me, the costume designer, the cinematographer (Benjamin Loeb), and the director (Kogonada). We were all making the same movie.

Yeah, that’s so important. What we love talking about on The B-Side Podcast and highlighting at The Film Stage––and as somebody who works as a producer whose job is to talk with crew leads and discuss what we can afford and how we can achieve it––is talk about how movies are made. It still feels like such an under-sung part of the process. To your point earlier: Christopher Nolan. He’s a genius, okay, we all know that. But who are the people who find the hat that J. Robert Oppenheimer wears? Somebody found that hat. Train Dreams, Clint’s incredibly talented. We know this, right? But who found the dilapidated train area in Washington? I like highlighting that stuff. Even down to production assistants. I always talk about one of my favorite moments in the history of award speeches is when Chloë Sevigny won a Golden Globe for Big Love and she thanked a production assistant for running lines with her. And I remember when I watched that, I was like, “Oh my God, that should happen more often.” People should thank the assistant who drives the crew van!

It takes a village. And you know, yes, the director is the auteur of the film, and we’re all working in service of their vision. But what I would say is, like, all these directors that I’ve worked with are so different in so many different ways but what they all share is that they share a strong sense of their vision. They know what they want. But within that, there is so much latitude for collaboration. They allow a lot of space for that. And to me, that’s the most fulfilling kind of movie to work on, because there’s space for me to bring ideas to the table. And I feel like, you know, coming from independent film, I worked my way up in New York City doing tiny, no-budget movies, short films, art department of one, two, three, all the way up. It was hard for me to, as I scaled up in budget and scope, it was hard for me to let go of the reins a little bit, because you’re so used to doing everything yourself and wearing so many hats. And I think that the superpower of some of these directors is that they surround themselves… they’re very clear about what they want, and then they surround themselves with collaborators whose vision they feel aligns with theirs, that they can trust. And I think that as a production designer who runs such a big department, it’s my job to do that, too, and to help people create their best work, because people who are creatively fulfilled will work harder, be happier, enjoy the process, and that makes everybody look good.

Do you have any final Train Dreams things to say as we come to the end of this talk?

There’s so much that I could say. The thing I’d say about Train Dreams is that I met Clint on Instagram. I feel like there’s so many ways to meet filmmakers. It was through the costume designer, who is Malgosia Turzanska. And she was actually also the costume designer on Maggie’s Plan. She’s a longtime collaborator, but also a very, very dear friend. She has been talking to Clint and had the lookbook and maybe sent it to me, and I was like, “Oh, wow, wow, wow, wow. I got to talk to this guy.” And so I DM’d him on Instagram, and he responded right away. And he was like, “Well, as it happens, I’m actually interviewing production designers. Do you want to meet?” So I said, “Okay.” And so, literally, the next day I met him. And the thing that we connected over was the work of the land artists, you know, James Turrell and Robert Smithson and Andy Goldsworthy, and like the bigness of that work, but also kind of the intimacy and personal feeling it evokes. And how the land art uses the land, like the earth, the surroundings as both material and canvas. And at any point, it looks like it could be reclaimed by the land. And that was kind of a philosophy that we adopted for how everything should look in this movie. Like, at every point in the movie, everything should feel like it had been there forever, but that it might also disappear at any moment.

That is a lovely note as we come to the end, because that is what it feels like. In my review of Train Dreams I reference there’s this line in the middle of The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, where Brad Pitt says, “I was thinking how nothing lasts, and what a shame that is.” In that movie this is in reference to Benjamin coming back to where he grew up and how it all seemed so different. But the thing that’s different is you. And that is what Train Dreams is, right? This guy lives this solitary life, he finds love, things happen. It’s a movie kind of draped in hope, and plenty of regret and guilt and what have you. And the beautiful thing about the movie is when you get to the end, you realize that you’ve just experienced the life of anybody, right? It could have happened in 1920, could happen in 1975, could have happened in 1815, could have happened now. It’s funny, After Yang there is also a little bit of that. Maybe that’s the thing! Maybe, Alexandra, that’s you. You’re just capturing the ennui of everything in your designs for these movies.

Well, that’s a great compliment. Thank you. It’s interesting, right? You have After Yang, that’s set in the future. It’s a very grounded production design, but I think it’s clearly a movie that’s designed. Right. But Train Dreams, on the other hand, is, yes, we’re telling the tale of a time long ago. It’s a period movie, but the production design is invisible. It’s completely invisible, because that’s what served that story. And so that’s what’s fun about being a designer is you get to do different things on every single project.

Train Dreams is now on Netflix.