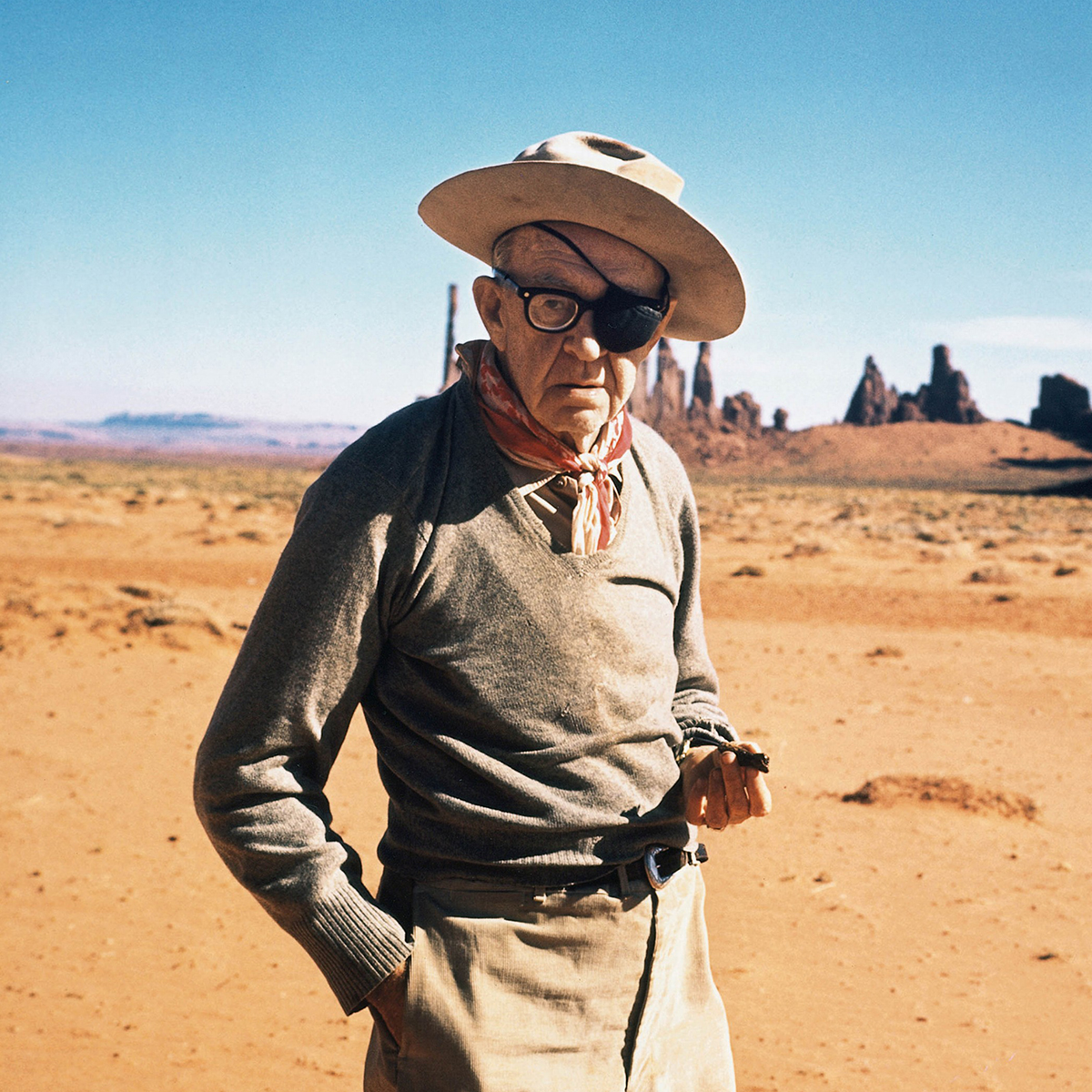

Is there a single more enigmatic director than John Ford? After many biographies, documentaries, and over half a century without the director’s presence on this Earth, to “print the legend” of John Ford has meant to paint him as a series of contradictions rather than the burly naval commander persona he so often played in public. He cast the athletic John Wayne as his ideal archetypal male protagonist, perhaps even a stand-in for himself at times, but the young Ford grew up weak and sickly in a boisterous Irish home in Maine. Wayne stoically talks to his character’s dead wife’s grave in She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, but the “real” Ford was known for being reduced to a blubbering mess when dealing with the deaths of his friends. Tales of his abuse––to cast, crew, friends––on set are legendary, but nearly everyone who suffered his harsh words continued to love and respect him anyway. This season of TCM’s podcast series The Plot Thickens works through the complex legacy of Hollywood’s greatest director by consulting a wealth of scholarly and archival interviews, some of which have never been heard before.

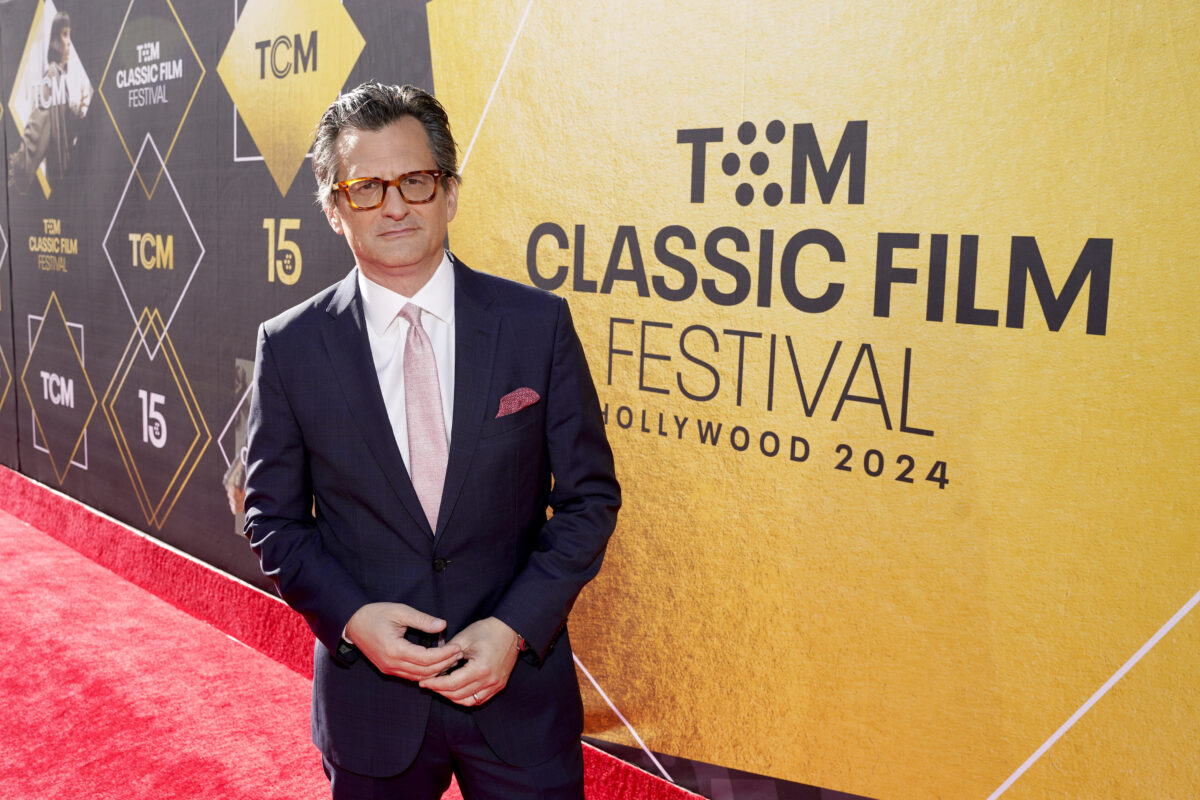

We talked to TCM and The Plot Thickens host Ben Mankiewicz about structuring this season around Ford’s missing D-Day film, a very rare interview with actor Woody Strode, the folly of trying to “solve” Ford, making a podcast appeal to the mainstream and the Ford-heads, and relating to a very special interviewee. Believe it or not, despite the fact that this season covers an historical person with a life lived long ago, spoilers do follow.

The Film Stage: When I was listening to the first couple of episodes of this season of The Plot Thickens it kind of seemed like we were in for a crash course on Ford’s life and works, but we eventually find out that the centerpiece of the show is about this missing Ford film. What made your team decide that the hunt for this film would be kind of like a core subject of the season?

Ben Mankiewicz: Well, the totally honest answer is that the initial thought was that would be the whole season––the process of putting that together. And don’t spoil this part [sorry, Ben], but we didn’t find the film. But we still knew there was a compelling story to tell even without finding it; we knew that other people had been looking for it, even if they weren’t as focused on it as a single project as we were. We had people look in the former Soviet Union, and I went to England to look in the Imperial War Museum. And we had a couple of people looking for us in various places in DC.

But in the course of trying to sort of get the whole story about that, we uncovered all this audio. Not just Ford himself, but from all these––you know, I won’t throw this word around––but all these legitimate legends of classic Hollywood talking about Ford. And so we just thought, being led by our podcast executive producer, Angela Carone, who has everyone’s faith and trust: this stuff’s too good.

What was really interesting about the search part was the deep dive into “What is with Ford?” Like, this incredibly complicated guy: what would make him either lie or brag or be so determined to tell everybody that he was in harm’s way on D-Day––which he was, by the way.

So then it just became: we’re selling ourselves short. We’re limiting ourselves. There’s too much good to tell here about Ford. And we have all this audio. And when I say no one had heard it, I mean, of course, people who went specifically looking for it had heard it, but––forget the general public––the overwhelming majority of even serious film fans have not heard most of these things.

And so we thought––being reliant on some really good Ford biographies and the willingness of those biographers to talk to us as well––that we would just endeavor to tell Ford’s entire story at that point. That only delayed things a couple of months––we just had to push everything back a little bit and refocus and re-outline how this would go, and at the center of it would still be this D-Day film and the search for it.

I noticed that D-Day itself is kind of the structuring device for the entire season. You tell Ford’s life up until D-Day and then how his experience at D-Day haunts his productions after. But it’s a huge life, and all of his biographies are so long. How did you decide what to include and what to talk about?

A lot of that has to do with the audio we had. We probably wouldn’t have endeavored to tell John Ford’s life without access to this audio. Not that it’s not a worthy thing to tell, but there’s a limit to how great a podcast can be if it’s just a documentary. And I love film documentaries, but you know, a documentary of talking heads, essentially, is all extras. So we include them, but it has to be built around contemporary interviews with Ford and the people who knew him best. And those were unquestionably the people who worked for him most––those who were connected to him, especially in the case of Katherine Hepburn.

We focused on the things we had, and almost everything about Ford is interesting. And almost everything we had to use did answer the core questions about Ford, which would be, like: “What motivated him? Let’s explore these seemingly pretty clear contradictions in the way he described himself and the way he behaved and vice-versa.”

And so how do we explore that? How do we tell that story? Because what we didn’t want was to make it a seven-part podcast that was only for film geeks or academics. We want you to be able to enjoy this and, to be realistic, there aren’t a lot of people going to listen to it who haven’t heard of John Ford, but maybe they just know that John Ford was an old-timey Western director. That might be the extent of their John Ford knowledge, and we want to make sure the podcast is accessible. The genius of the people at the podcast team––again, led by Angela––is that they can do that without in any way, and this is not the right phrase but: dumbing it down for people who are serious cinephiles.

We also didn’t want to do a podcast where we thought: here are 15 John Ford films and why they matter. That’s an interesting podcast, but that’s not our mission statement at The Plot Thickens.

Speaking of Fordheads, one thing that might be surprising to them is ––

Did you say Fordheads?

Yes. Ford-worshippers, let’s say.

Yeah, Fordheads. I may steal that.

There seems to be very, very limited interviews to work from. You include a lot, but were there any in particular that really jumped out as being the Rosetta Stone of understanding Ford or, alternatively, just one where he goes on talking for about 50 minutes?

No, because he doesn’t do that. I don’t think there’s a Rosetta Stone for understanding Ford. That’s part of the thing. I mean: the more you hear of him, the more context you put in. You get sort of a general understanding that this is a guy too filled with contradictions. Like so many of us, but I don’t think there’s a Rosetta Stone for understanding Ford.

At the end, what I’m comfortable spoiling is that we’re not trying to leave you with an “a-ha!” What you want is: “Wow, that’s an interesting guy.” What was certainly true for me is that you think afterwards that it was a lot more complicated and a lot more interesting than I realized. Part of it is just the element of hearing Ford. And I’m now wondering, in my audio tracking of this as I read it, whether Ford’s own voice influences my own. [Laughs] Because I listen to this now and I just have this hint of graveliness that I don’t know that I would have had if it’d been about somebody else. I certainly didn’t try, but there it is. And I’m like, “Wow, what’s happening there?” But everybody seemed to be okay with it at the time. But I’m struck by it. And my wife was struck by it, too. So I feel like that was just, you know, listening to John Ford. I guess I did it without even realizing it or maybe it was just that I thought, “Okay, I’m telling a Western story.” But it was not intentional, I can definitely tell you that.

But just hearing him is understanding a little bit, and the more often you hear him say, “You know, none of this meant anything. What are you talking about? I didn’t do any of this intentionally,” the more I think he knew. I don’t think he sat and pondered the imagery and the subtlety that we now perhaps see in it. But he cared about images and he cared about subtlety, right? He liked the subtle way that people communicate. I imagine that’s ultimately the takeaway. And that’s what kept getting to us. That’s what kept speaking to us.

You mentioned there’s quite a few rare audio recordings that you found not many people have listened to, other than maybe biographers Scott Eyman or Joseph McBride or people like that. I just finished listening to Episode 5 and there’s that great, never-before-released Woody Strode interview. Were these particularly helpful?

For me, that was just about the most interesting part of this. So Ford is this enormously complicated guy, full of really interesting contradictions. Right? And among them, of course, is this love that he has for the community that is formed on a particular film project. A community of artists––a term you would never use in a billion years, by the way. Please point out that I said Ford would never have used that term. [Laughs]

And then Ford would always bring this uncomfortable degree of tension to that community by demonstrating very clearly his hostility toward at least one member of that community. And there’s a great line in there, I think it’s from Ben Johnson, about how Ford loved nothing more at the end of the day to come, gather with everybody else. But––and you weren’t allowed to drink on a Ford set––they’d have a drink, and say it was always better for them before Ford got there, because he made everybody kind of uncomfortable.

I don’t know whether he got that, but he craved this, and nowhere is that better demonstrated than in his treatment of Woody Strode. Especially as he’s making Sergeant Rutledge, one of the most important Hollywood films to deal with race in America in a meaningful way––particularly in the 1950s when there had been so few.

Well, here’s a really important one in a genre that has been unkind to anyone other than the people who conquered the West and told that story. So here’s an important movie, and Ford gives Woody Strode the role and makes the movie. Those are two big wins, right? And then, 1) sort of tricks him, gets him drunk for a performance, and then 2) uses demonstrably hostile racial language in dealing with him. Right? And then with other Black members of the cast, he sort of drives this fissure through because he thinks that’s the only way he can get a good performance out of him. So you’re like “Wow, what’s going on; what is that?”

And then just to add the second layer to this multi-layered cake, Woody Strode feels more strongly about Jack Ford than anybody else who worked for him––so much so that he’s sleeping on the floor in Ford’s house as Ford is dying to take care of him. There’s an irony there that this guy who craved the community and then sort of disrupted the community with his hostility and his language then, nonetheless, reaped the benefits of that community he craved at the very end by having this––particularly this one specific––really, really interesting guy himself, Woody Strode, come out to the desert to be with him as he dies. That’s a very complicated and interesting man. Because, you know, Woody Strode’s no fool. I just sense that if somebody said, “Woody, how could you do that with the way he treated you?” he’d be like, “What? How could I do that? What are you talking about? This is John Ford. I’m going. I’ll be back in a few days.”

I’m interested in that guy who engenders loyalty in spite of his behavior which stifled the very thing that he craved.

In the biographical parts of this season, there’s this emphasis on paradox. John Ford is absolutely known for paradoxes, but there are paradoxes maybe within those paradoxes, because even if you were to split it between the machismos in his movies and the blubbering, emotional Ford in front of Katherine Hepburn, there are counterexamples to both of those characters as well. You have emotional male performances in Four Sons. There are a lot of blubbering mama’s-boy characters in Ford’s oeuvre. How did you go about tackling this complicated masculinity? What aspects of that did you look for in his films?

Well, I don’t know if we were tackling it as opposed to just discussing it. Because tackling it suggests that you brought it to the ground, right? Like, it was running away from us, we caught it, tackled it, and now it’s clear and that down is over.

It seems very clear that John Ford, as the 1950s wore on into the 1960s, whether he actually sat down with anyone––well, he did. He acknowledges that the Native Americans weren’t treated well in Hollywood Westerns. It’s a little like if Thomas Jefferson said, “There’s some questions about the Founding Fathers,” and you’re like, “You’re the most important one!” So when John Ford says there was troubling stuff in Westerns, he’s talking about John Ford. He’s certainly the most influential.

So we know that that troubles him. And what sort of goes with that is that, as the ’60s came, and as the country softened, the idea of men being emotional became more acceptable. He seemed not to run from that. And we certainly see that in Liberty Valance and, as you said, Four Sons and––not quite masculinity––but in 7 Women where he sort of gave over the role of the men to the women. [7 Women] might be a stretch, but it just occurred to me. But it certainly speaks to his sensitivity at the end of his life. You know, it’s pretty significant that that’s his last film, even though, of course at the time he didn’t expect it to be his last film.

So obviously the idea of what it meant to be a man was very important for Ford, and I think it changed. And also there’s a contrast there––because this is a guy who was not only an artist in the sense that he was just influential, but his films are beautiful, right? I mean, he cared as much as anybody about how movies looked. But get him to talk about that, and he’ll say “I pointed the camera, it was a nice shot, I took it, what are you talking about?” And he also said “I went out to Monument Valley, because yeah, it was pretty, but mostly it was a way to get away from everybody.

All those things can’t be true. It can’t be. He had to know, right? He had a gentle side, as Katherine Hepburn [revealed]. Thank goodness for that. We don’t use her [interview] that much, but her presence in this is really critical to being able to tell the story completely. First of all: she’s a trustworthy narrator. We just trust that her version is probably true. Because we sense in her that she would have no interest in deceiving anyone; that’s sort of her reputation.

I think Ford’s idea of what it means to be a man changed, and I think you can see it in the movies. You know, there’s some consistency, but the 17 years between Stagecoach and The Searchers certainly already demonstrates a different idea of what it means to be a man. And then with Liberty Valance and Sergeant Rutledge.

We see this progression, and I wonder how much of Ford’s life was spent playing the part of a man. I don’t mean that he wasn’t one; I mean that there was an image in his head about how men acted, what they did, how they behaved, what they admitted to, what they copped to.

I had a conversation in an interview last week about the five years or so where I was a film critic. And I didn’t like it. I liked that it sort of advanced my career, right? I didn’t mind. I liked the critics. I did most of them. I think film criticism is super important; I think it’s a very valuable tool and we need to have it. I was just bad at it. I could fake it pretty well because I was a pretty good broadcaster, and I was getting better.

But I always felt like I was imitating a film critic. I would say things I didn’t really believe, or surely didn’t feel, because other critics talked about the music here and why a shot was structured in a certain way there. I really only noticed what they were saying to each other and how the story got advanced. And that’s always been what’s interested me about movies. And I didn’t like not liking a movie––I really admire people who make movies. I love actors. Obviously I love writers, as I come from a family of writers. I love filmmakers. I didn’t want to see a movie that someone slaved over for sometimes five, six years and then being among a group of people who were like: this was terrible.

And I couldn’t really reconcile that. And I know some people can. And if you’re going to believe that film criticism is valuable, then obviously that’s gotta be part of it. But I felt phony, and I wonder how often Ford felt like he was playing the role of an early- to mid-century American man and what he thought he would be. And, you know, we barely get into it with the notion of his openness––whether it’s bisexuality or men in general. Like, did that really play a role or was that just a bit of… I mean, there was a lot of that in Hollywood. There was a lot of sexual openness in Hollywood, and there’s a bit of that where it could be, “Oh I can do anything I want. I’ll try this.” It’s unlikely with Ford, but I’m curious about it. And that the mere mention of it by somebody would cause him to write off a friend [Harry Carey] for a quarter of a century. Like, there’s not a lot we can do with that and nobody really wanted to explore it, except in the sense that, again, it adds to this idea of: who really was this guy? And what did he really want out of life, how much of his softer, artistic side––I don’t mean to suggest that if you were gay you’d be softer––but I mean how much this openness might make you feel compelled to stifle [that side].

One of your big interview subjects, Dan Ford––I’m curious how he feels about his grandfather’s legacy and about all of us talking about all these kinds of paradoxes about his grandfather. And I’m also curious about your relationship with that since you’re also a grandson of Hollywood royalty.

I don’t think he’s wholly dissimilar to his grandfather in some ways. I mean, he’s certainly more in touch with himself than his grandfather, but that’s a pretty low bar. First of all, my relationship with Dan is excellent; I really like Dan. And, you know, Dan is a tell-it-like-it-is guy, even if maybe that isn’t like it is.

I like that kind of person. He likes to laugh. And he’s been laughing about himself and about his grandfather. You know, he’s a talented guy himself, Dan is, and from a very young age he thought that preserving his grandfather’s legacy was a really important thing for him to do and for the family to do. And I think it’s important to remember that at the time Dan started doing it, there was no certainty that Joseph McBride or Scott Eyman would be writing biographies of John Ford, right?

Like, he didn’t know how we were gonna view John Ford in 2024. He didn’t know Steven Spielberg was gonna memorialize him in the way he did in The Fabelmans. I mean, he knew he mattered but that the jury was still out on his legacy. When Dan Ford started doing this, TCM wasn’t on the air. There was this idea that you thought you were probably speaking to a much smaller community than it turns out you are.

So anyway: I think that Dan loves his grandfather. I think that he finds the hair-pulling that we do about trying to figure out his grandfather––I know, he also wonders about it. He wonders about the very same things that we do. I really liked talking to him and what we’ve done to promote it and the interviews that we’ve done before. But I liked Dan when I met him in Lone Pine, California on a panel. You know, at the Cowboy Film Festival there. I mean, I call it the Cowboy Film Festival, but it’s not what it’s called––the Lone Pine Film Festival. And Dan is a hard guy not to like. He’s also a great, well, he’s not a great-grandfather. He’s a terrific grandfather.

But much more fuss in general has been made over John Ford than Herman Mankiewicz, my grandfather––as it should be. Ford had a much more lasting and successful career in Hollywood, but I love writers too. And when there were two biographies coming out within a year of each other about the brothers’ relationship, about Herman and Joe, and then David Fincher made his movie, I thought that was great. And when the family was like, “Well…” I’d be like, “The movie’s called Mank. Mank! Are you kidding? This is all unbelievable. This is all wonderful, amazing.” And I think that Dan Ford thinks the same thing. You know, here’s us doing the podcast, and Spielberg has this incredibly memorable scene with David Lynch as Ford. I think it’s pretty great. And I think he thinks the same thing.

Is there any lesser-known Ford that you like to champion? I’m glad you included Wee Willie Winkie on the podcast.

Yeah, I don’t know if that’s the one I’d pick to champion. [Laughs] You know, I’ve said this before, but I don’t even know if they used it––but to me, definitely, it’s The Last Hurrah. I don’t think we mentioned it one time, but to me it’s a reminder of the abundant talent that Ford had outside of Westerns. Like we know that he’s the greatest Western director who ever lived––that seems like a pretty safe call.

But yet he won four Oscars and not one of those movies was a Western. And then he makes this political movie about the mayor of Boston with Spencer Tracy. They don’t call it Boston, but it’s Boston. Spencer Tracy is the mayor running his last campaign, the last hurrah. I’m a political junkie––I come from a political family––and, to me, if I were to tell people who want to understand American politics quickly, I would tell them to watch The Candidate and The Last Hurrah.

Those movies, more than anything else, make it clear what politics is, and you could be disgusted by that or sort of charmed by it, and I’m definitely gripped by it. And The Last Hurrah is this magnificent piece of work that has long been my underappreciated––in the general public; movie people certainly know it––Ford picture. But it’s John Ford and Spencer Tracy for crying out-loud! It’s definitely good.

Listen to the first episode of The Plot Thickens below and more here.