Spike Lee, Chantal Akerman, Wong Kar-wai, Steven Spielberg, Claire Denis, Pedro Almodóvar, Guillermo del Toro, Christopher Nolan, Kelly Reichardt, Hirokazu Kore-eda, Charles Burnett, Lynne Ramsay, Lee Chang-dong, Yorgos Lanthimos, Mia Hansen-Løve, Bi Gan, Michael Haneke, and Hou Hsiao-hsien. Those are just a few of the directors who have been featured at New Directors/New Films throughout its 52-year history.

With this year’s edition, taking place at NYC’s Film at Lincoln Center at the Museum of Modern Art, kicking off this Wednesday, we’ve rounded up 17 features worth seeing––some of which we caught at Sundance, Berlinale, Locarno, and beyond, and others new to us at the festival. All in all, this 52nd edition presents another exciting example of the boundless creativity of emerging filmmakers and points to a bright future for the medium.

Check out our picks to see below and learn more here.

Astrakan (David Depesseville)

Astrakhan fur is unique: dark, beautiful, and stripped exclusively from newborn lambs, even ones killed in their mother’s womb. (Stella McCarthy once said it’s like wearing a fetus.) That ruthlessness—a sense of lost innocence; blood sacrifice—runs deep in Astrakan, a new film from France and one of the better in Locarno this year; and if that title isn’t enough to give pause, plenty else in the opening exchanges will. The first act is a procession of flags, both red and false: at the opening the protagonist, Samuel, lightly goads a snake in the reptile house of a zoo; moments later a rabbit is hung and skinned in his kitchen with all the ceremony of a boiled kettle; queasiest of all, an older lad is seen walking toward the house cradling berries in his shirt, just enough that the lip of his underwear and his midriff are left strikingly visible. – Rory O. (full review)

Coconut Head Generation (Alain Kassanda)

In Coconut Head Generation, students form a weekly film series at the University of Ibadan, the oldest collegiate institution in Nigeria. In his sophomore feature documentary, director Alain Kassanda examines how this club isn’t just a place of belonging and watching cinema, but also for collective action against the systemic downfalls at Ibadan and the world. Throughout profound moments of speakers highlighting intersectional inequalities, Kassanda inserts moments of students performing recreational activities to inform audiences that they are at the earliest, precarious stages of their adult years. As the film’s scope expands, a coming-of-age celebration of youth evolves into a resistance to perpetuate the status quo. – Edward F.

Chile ’76 (Manuela Martelli)

Manuela Martelli’s debut film opens with a sequence that perfectly captures the tone and themes Chile ‘76 will explore. Carmen (played by Aline Kuppenheim) is at a paint shop, choosing and mixing the color that she’ll use at the beach house she has with her husband, a shift head at one of the most important medical institutions in Santiago, Chile’s capital. While browsing an almanac with pictures of European cities, pointing at colors of sun-kissed buildings, we can hear a disturbance outside: a woman is being pulled over by the military and yells as she’s taken away. – Jaime G. (full review)

Disco Boy (Giacomo Abbruzzese)

To Disco Boy’s credit, while its core themes and imagery are second-hand, it does attempt to build, expand on, perhaps modernize Beau Travail, not unlike Helena Wittmann’s recent Human Flowers of Flesh, which premiered last year at Locarno (and actually featured Lavant playing an incarnation of his Galoup character). It’s also perhaps the first leading role of his glittering career to date where Franz Rogowski is miscast, feeling inappropriate or perhaps too worldly for the naive military grunt at the center; either way, the film’s debuting director Giacomo Abbruzzese attempts drawing out a performance that hits predictable notes of machismo, despair, and anguish. – David K. (full review)

Earth Mama (Savanah Leaf)

Conceived with a remarkable amount of filmmaking confidence, Savanah Leaf’s directorial debut Earth Mama follows the trials and tribulations of a pregnant single mother struggling to get by day-to-day, restricted to seeing her other two children, currently in foster care, only one hour per week during supervised visits. With a history of drug addiction, she must find her way through a system that stacks the odds against her, exploring the possibilities of adoption and the pain of knowing the court may immediately take away her soon-to-be-born baby. It’s a difficult, demanding portrait of a life in shambles, susceptible to being relegated to poverty porn or a social-realistic bent that surrenders to one-note misery. It’s a miracle, then, that Olympian-turned-director Leaf finds both the humanity and beauty of every frame, bringing empathy to an impossible situation and delivering an abundance of grace notes. – Jordan R. (full review)

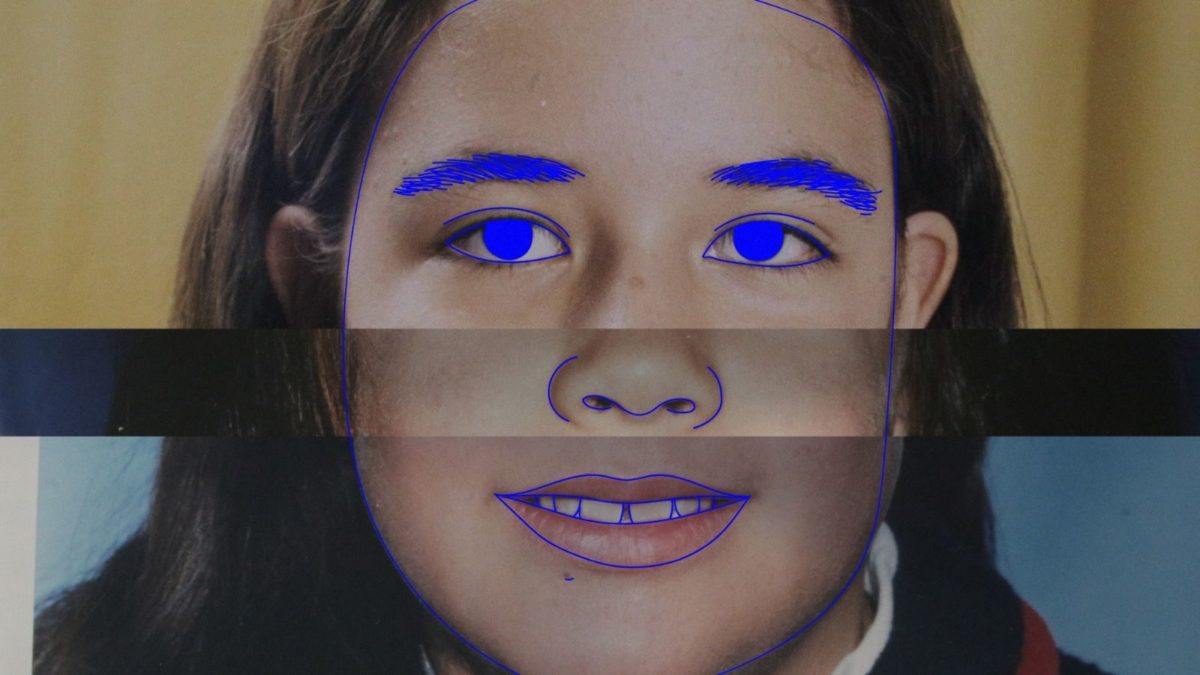

The Face of the Jellyfish (Melisa Liebenthal)

One day, Marina wakes up with a face that isn’t her own. Her mother doesn’t recognize her at times, and her grandmother can’t hide that she can’t call her Marina. As she refuses to see her boyfriend and co-workers, she starts crafting collages using old pictures from close relatives to find out where her new face comes from. Those collages are playfully edited into Melisa Liebenthal’s film, rhythmically giving it an experimental edge. Digital face recognition, surveillance, and even deepfakes are hinted at in this spirited, sometimes hilarious film that verges on a treatise on identity and self-representation. – Jaime G.

Gush (Fox Maxy)

If you get bored at any point during Gush, wait 10 seconds and the image and music will change to something completely different. Director Fox Maxy, making her feature debut, accomplishes something remarkable. At first glance Gush couldn’t feel more chronically online: a jittery montage of dancing, performance art, friends talking in their car, TV clips (threading a Naomi Campbell interview about her negative experiences in the modeling industry throughout), and pop remixes. Yet it’s cheerful and positive throughout. Even if Maxy’s aesthetic owes something to the rush of TikTok, she carefully foregrounds friendship and communal spaces. Gush avoids becoming exhausting by being so optimistic. – Steve E.

Have You Seen This Woman? (Dušan Zorić and Matija Gluščević)

Vacuum cleaner Draginja (Ksenija Marinkovic) loses her consciousness when she stumbles upon a dead body in Dušan Zorić and Matija Gluščević’s debut Have You Seen This Woman? Initially beginning as a mystery, the Serbian directors veer into a surreal, humourous, Lynchian character study of a woman living in a patriarchal society as Draginja envisions her life differently each time she encounters another person. Her personas after each interaction become bewildering and jarring, yet sobering and resolute, which make up her personality. The result is a hypnotic spiral of defining identity. – Edward F.

The Maiden (Graham Foy)

Split into two distinct halves, Graham Foy’s debut The Maiden starts off as a look at two high school students who each lose their best friend (one from a tragic accident, the other from getting older and drifting apart). And what may seem a quiet, meditative portrait of grief and coming-of-age opens into something else entirely once one of its leads decides to head into the woods just outside the suburban sprawl they call home. If many filmmakers have taken inspiration from Apichatpong Weerasethakul in the last decade, few have been able to tap into his emotional frequency. Foy’s work pulls that feat off without ever feeling too indebted to his influences (mainly Tropical Malady), which is part of why The Maiden is one of the year’s best directorial debuts. – C.J. P.

Maputo Nakuzandza (Ariadine Zampaulo)

A jogger, a runaway bride, and civil servants breathe and run Mozambique’s capital Maputo in Maputo Nakuzandza (translated to Maputo, I Love You). While the eponymous radio station provides delightful tunes and the attention-grabbing headline of an alleged kidnapping of a fiance, director Ariadine Zampaulo shies from the radio cast to something more profound. Instead she displays the wonders of city life amidst sensational journalism. She shares with audiences what the depicted residents think most: how to preserve their mindset for the future. Through predominant diegetic sounds, blending fiction and nonfiction, and “a day in the life of” structure, Maputo Nakuzanda is a rhythmic testament to one’s search for interconnectedness. – Edward F.

Metronom (Alexandru Belc)

Romanian director Alexandru Belc’s Metronom includes an extended party scene set to wall-to-wall music. Unlike Cold Water or Lovers Rock, it’s sapped of energy. Ana (Mara Bugaran) is more concerned with meeting up with her boyfriend Sorin (Serban Lazarovici) but is arrested at a party when the secret police learn of her friends’ plans to send a letter with song requests to a Radio Free Europe DJ. Belc’s style absorbs the repression of the time and country: Metronom was shot in a boxy Academy ratio with a dark palette and few close-ups. It follows the path of the Romanian New Wave without adopting the same neo-realist influences or dark humor. The ease of wiping out teenage rebellion hits far harder than the rebellion itself. – Steve E.

Milisuthando (Milisuthando Bongela)

Conveying complex political and social issues through an immensely personal lens, Milisuthando Bongela’s debut feature is a sweeping, staggeringly original attempt to unpack the oppressive grip of apartheid in South Africa. Across its five chapters, some look back on history with a newfound awareness of a colonial past and its generational damage while others take a pared-down avant-garde approach in reckoning with the present and future by giving space to weighty conversations. Milisuthando is the kind of documentary that should be essential viewing––not only in American history classes, where apartheid is often a footnote, but in filmmaking education to show how the most affecting way to convey monumental struggle is through a singularly individual perspective. – Jordan R.

Pamfir (Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk)

A riveting father-son story set in the criminal world of smuggling on the edge of the Ukrainian border, Dmytro Sukholytkyy-Sobchuk’s debut Pamfir has a remarkable sense of location. Astonishing tracking shots center on our foreboding lead Leonid (Oleksandr Yatsentyuk) as he picks up the pieces of his life to make ends meet for his family. There’s a lived-in sensibility to its world, giving space for raw, unfiltered emotions to play out in regard to regrettable decisions our characters make in a bid both for survival and a familial connection. – Jordan R.

Petrol (Alena Lodkina)

Upending familiar territory for an emerging director––i.e. making a film about an emerging director––Alena Lodkin’s Petrol is an enchanting inquiry into performance, creativity, and the struggles of collaboration. With a firm grasp on evocative film grammar, there’s not a single frame or cut that feels like an afterthought, leading to a captivating atmosphere as fantastical flourishes pop into the world of film student Eva (Nathalie Morris). For making a fitting double feature with James Vaughan’s similarly lo-fi, charming Friends and Strangers, there’s certainly something promising brewing in the Aussie indie film scene. (Also, bonus points to Lodkin for nailing the film-student trope of not recognizing Spielberg’s greatness until well past graduation.) – Jordan R.

Remembering Every Night (Yui Kiyohara)

Our House helmer Yui Kiyohara’s second feature cements her as one of the most interesting new Japanese directors of the decade, as she shows a day in the life of three women in the suburbs of Tokyo: a mature woman that just lost her job wanders around the streets trying to fill her time; a gas-meter reader finds an elderly man that wandered off his home and is being looked for by his family; and a university student reminisces with a childhood friend while mourning the death of another. Paths are crossed here and there, but the film isn’t interested in the connections––rather those empty moments in-between. – Jaime G.

Safe Place (Juraj Lerotić)

Juraj Lerotić’s first feature comes to ND/NF with an especially high reputation under its belt, having brought successive festival audiences to tears for its intense portrayal of a severe mental health crisis, inspired by his own familial experience. With the Croatian director also playing the lead Bruno, he doesn’t skirt manipulation as he depicts his flailing, uncomprehending attempts to protect his brother Damir, who has been hospitalized following a suicide attempt. A real-time thriller structure and tempo emerges as Bruno and his mother riskily attempt to ferry him away from the Zagreb psych ward toward private healthcare in Split. – David K.

Tótem (Lila Avilés)

The characters of Tótem don’t just appear onscreen; they take it over. From the top there’s the patriarch Roberto (Alberto Amador), who speaks using an electrolarynx and, when not dryly cajoling his flock, enjoys pruning a handsome Bonsai. There are his daughters Alejandra (Marisol Gasé), who we meet mid-phonecall, mid-ciggie, and covered in hair dye, and Nuria (Montserrat Marañon); their children, the young Marthe (Saori Gurza) as well as a gamer and a stroppy teen whose names I lost track of. There is Alejandra’s brother, an artist named Tona (played by the screenwriter Mateo García Elizondo), and his partner Lucia (Iazua Larios), with whom he has a daughter, Sol (Naíma Sentíes). This lively ensemble are joined here and there by a mystic, a party of friends, a cat named Monsi, two dogs, three snails, a parrot, a scorpion, enough plants to fill a modest botanical garden, and a pestering drone. – Rory O. (full review)

New Directors/New Films takes place from March 29-April 9 at Film at Lincoln Center and the Museum of Modern Art.