I wonder when we’ll grow numb to movies about the COVID-19 crisis. Anyone saying they already have is either lying or living a life of privilege wherein the continued ebb and flow of hospitalization numbers has yet to personally impact them. They’re also the ones posing the biggest threat to those who’ve yet to take a breath because they’re the ones who care more about a “normal” that may never exist again than the health of a marginalized stranger who never experienced that same “normal” before the pandemic let alone now that we’re still very much inside of it. Watching Matthew Heineman’s documentary The First Wave isn’t therefore a casualty of diminishing returns due to a false sense of redundancy. If anything, it proves more powerful from accumulation.

Proximity plays an impact too considering the best-known COVID-19 documentary thus far was 76 Days. Watching Wuhan cope with the crisis as its epicenter is one thing, seeing that same helplessness at home is another. Heineman spent the first four months of the pandemic at Northwell Health’s Long Island Jewish Medical Center in New York. With a two-person, rotating camera crew stationed in an unused conference room, they roamed the halls and documented what for all intents and purposes was a warzone triage center. They show medical personnel running to rooms as lights and alarms go off. They give us a front row seat to the journey from hospital bed to makeshift refrigerator truck morgue. And we witness how alone nurses operating iPad screens with family truly were.

That last part is the most emotionally raw because we can’t help but realize the cost of what occurred to the frontline heroes made to endure a never-ending cycle of sorrow. You go into a film like this knowing you will see death—the crash cards, CPR, body bags, and final breaths. You don’t, however, imagine the pain of those who can no longer detach themselves from that suffering. These doctors and nurses are used to losing, but not multiple times a day with no ability to excuse themselves from the grief. When loved ones can’t be by the side of the deceased to hold their hand and say goodbye, they must rely on these professionals to facilitate that moment for them as an unprepared surrogate.

It’s no wonder then that many prop up certain patients as rallying cries. We can imagine the subjects at LIJ had many others beyond Brussels Jabon and Ahmed Ellis, but they are the ones Heineman is able to focus upon because they do provide that hope. Dr. Nathalie Dougé laments in a candid breakdown that the lack of patterns and preparation has made the entire ordeal that much worse since someone who appears to be turning a corner one moment might be dead the next. Heineman isn’t averse to showing these instances, but he needed a couple wins too to counter that horror with optimism even if it’s in very short supply. Showing the nurses wishing Jabon and Ellis well is part of their arduous journey to recovery.

Jabon and Ellis’ connection as first responders adds a layer to the tragedy by reminding us how vulnerable they are. Brussels is a nurse who lives with other nurses (her husband included) that became the only one to be hospitalized when COVID tore through their house. She was pregnant at the time and needed an emergency c-section before intubation—making her story about the baby’s survival too. And Ahmed is a school safety officer with the NYPD whose wife is also a nurse. She knows the danger of what’s going on and can appreciate the process that necessitates her children only seeing their father through a tablet screen. Their families’ understanding of the chaos allows Heineman unfettered access inside their homes too to tell the whole harrowing truth.

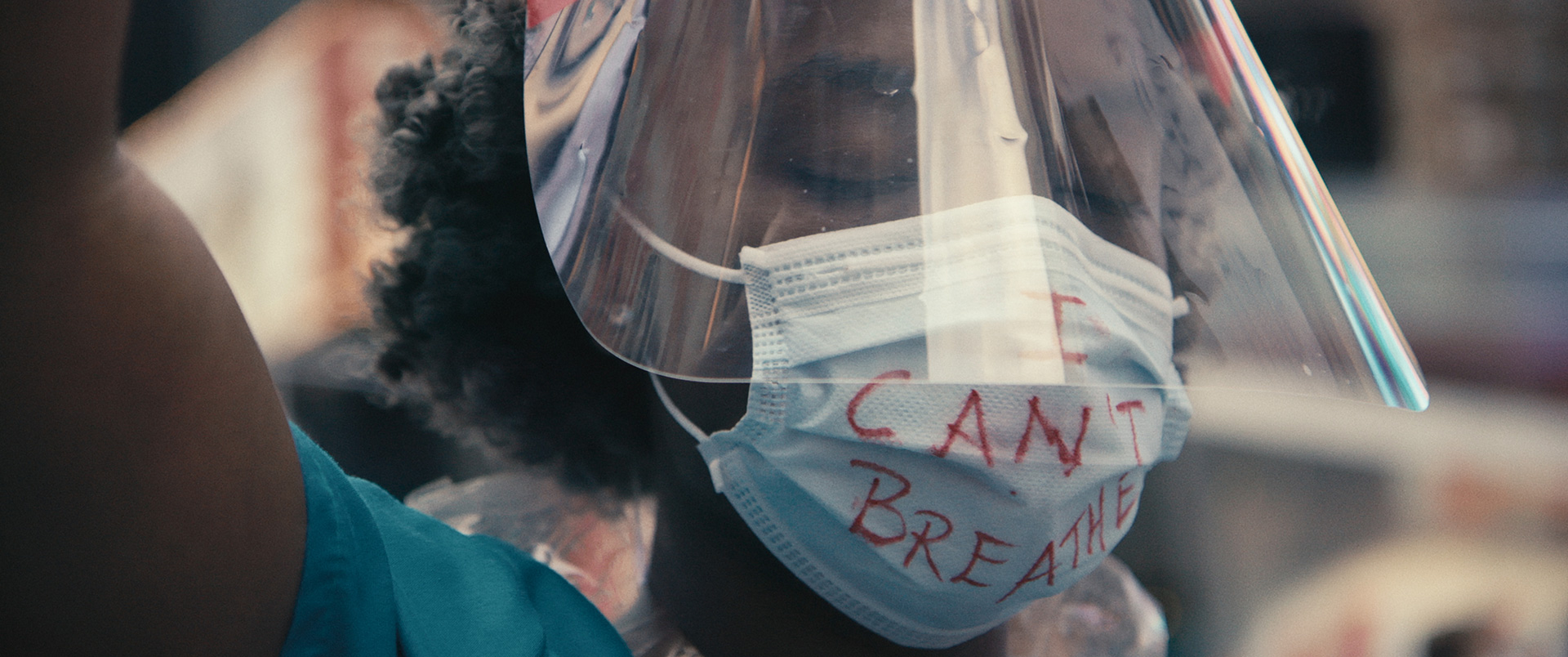

Dougé as the third prong of this main trio provides the opposite perspective as a healthcare provider removed from the familial bonds of patients’ lives as well as another piece to the overall puzzle being a Black woman dealing with the George Floyd crisis that was also unfolding. Heineman and company follow her as she goes into the streets to join the protests and try to tell other men and women who are hurting to be careful and not risk their lives at a time when she’s seen too many Black and Brown bodies perish. The pain she is feeling is so heavy that you almost forget she was also a part of one of the film’s most uplifting moments: a surprise Happy Birthday remote get-together via Zoom.

It’s easy to forget those highs, though, in the face of so many lows. No matter how inspiring it is to see Jabon and Ellis get de-intubated and begin their physical struggle to return home, the reality that they’re but two survivors amidst thousands of victims in NYC alone is always at the forefront of our minds. And if we’re thinking about that disparity a year-and-a-half later, you can’t imagine what these medical professionals are feeling in the moment as they risk their lives with double masks and face-shields in the hopes it will be enough to save them and their families from similar fates. Good on the hospital for having therapeutic roundtable discussions with their staff (Heineman shows one) because few will escape the effects of PTSD.

They will, however, have this memorialization of their work. The First Wave is perhaps more about reminding them of the good they accomplished despite all odds than a country that already appreciates their sacrifice (Heineman of course splices in a quick look at New Yorkers banging on pots and pans to begin his chapter on April 2020). This film portrays the perseverance of a community ravaged beyond imagination (we hear a newscaster exclaim that NYC currently had more COVID patients than any country in the world) whether those on ventilators, those assisting them, or those forced to wait. And it ends with the sobering knowledge that a second wave was coming. They would need to rely upon what they learned to ensure the sacrifices on-screen weren’t in vain.

The First Wave is currently in limited release.