Ahead of the Academy Awards, we’ve reviewed every short film in each category: Animation, Documentary, and Live Action.

Animation

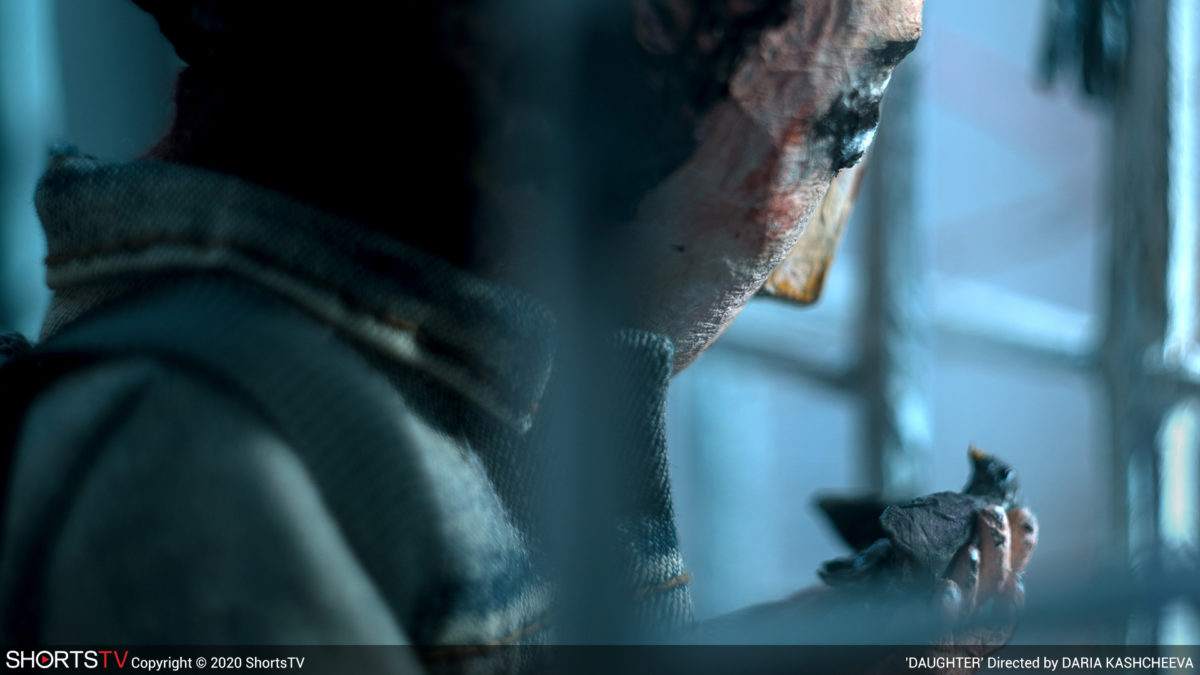

Daughter (Dcera) | Czechia | 15 MINS

Our lives are full of regret. Sometimes we possess the strength to overcome it. Sometimes we don’t try until the opportunity is already lost. This risk is present at the heart of Daria Kashcheeva’s Daughter and its father/daughter duo quietly at odds while he lies in a hospital bed. Neither is willing to break the silence and we’re unsure why until a crash is heard and a bird found beneath a broken window. It jogs both characters into a state of remembrance: the daughter recalling a moment where her dad let her down and then her returning the favor years later. The distance between them is revealed as something both have manifested in their heads, but its power refuses to let them confront its pain.

Shot with an extremely shallow focus, shaky cam aesthetic of which I cannot fathom the logistics considering the whole is a stopmotion enterprise with hand-painted maquettes, the emotional turmoil and struggle shines through from start to finish. We feel the disappointment these characters experience when the moment they each need love is met by what they construe as a lack thereof devoid of the necessary context to understand the complexity of each situation. He doesn’t actually ignore her in her time of need. He’s simply distracted and trying to solve one problem before the next. She conversely isn’t pushing him away later, but simply finding herself caught in a public sphere wherein his display of affection conjures more embarrassment than affection. These “slights” inevitably fester nonetheless, though.

And now they’ve reached a point where moving past it might be a “now or never” ordeal. Will one of them offer a hand of forgiveness before it’s too late? If so, which will it be? Since they’re caught in reverie, we’re also forced from the hospital room to view the past. By the time we return, who knows what we might find? Will the bed be empty? Will her father reach out with arms open wide? Will she inch closer in a bid to let years of seemingly irreconcilable differences fade? You’ll have to watch to find out. Either that bird dies along with their relationship or it springs back to life from the ashes of uncertainty. Hope for a second chances exists … until it doesn’t.

B

Hair Love | USA | 7 MINS

The producer list for Matthew A. Cherry’s short film Hair Love is insane. Jordan Peele. Peter Ramsey. Gabourey Sidibe. Gabrielle Union. Dwayne Wade. And those are just the ones I recognize. With hundreds of Kickstarter backers and co-directors Everett Downing Jr. and Bruce W. Smith also attached, the project would ultimately land at Sony, garner huge buzz online, and earn an Oscar nomination. That’s quite the journey for a children’s book that only dropped in May itself. With Vashti Harrison’s playful yet detailed illustrations begging to be brought to life, however, it’s no surprise that it would find such massive success. The world needs positive representations of the Black experience and one focusing on natural hair, fathers and daughters, and confident beauty proves a perfect catalyst.

It starts with a little girl realizing today’s the day. We don’t know what her excitement is about, but the calendar has a heart and she couldn’t be more enthusiastic about the prospects. First things first, though: she must do her hair. A mess of curls and tangles unleashed from a bed cap, she’s calmly undeterred. Her cat conversely carries obvious skepticism, but the hope is that a YouTube channel’s assistance will solve the problem. Judging by her quizzical reaction and the shock of her father upon completion, however, that hope is squashed. Will he take up the challenge and be the hero his daughter needs? Or will he glance at his watch and simply put a hat on her head so they can rush to their destination?

You may not think the decision is that dire, but you’d be wrong considering the systemic prejudice our society places upon Black women’s hair. The decision to cover it up therefore holds weight beyond the notion that doing so could be dismissed as a casualty of laziness. And since the whole idea here is to show young Black girls that they are beautiful no matter what people might say, you better believe her Dad is going to do his damnedest to give her the hair style she desires. There’s more to it than that after revelations are uncovered, but this added context is about mirroring and complexity rather than shrouding the importance of what’s happening beneath potential tragedy. It’s about perseverance, love, uniqueness, and pride. It’s about identity.

B+

Kitbull | USA | 9 MINS

It’s always wild to see a Pixar production that isn’t rendered in three-dimensional computer graphics, but I guess that’s kind of the point of the Disney+ showcase entitled SparkShorts. A collection of work from Pixar artists that feels like a venue for unique voices and experimental aesthetics, it’s no surprise that one would find its way onto the nomination list for an Animated Short Oscar. That it comes from a woman shouldn’t be undersold either since the studio is notorious for being slow on both the gender and race parity scales. Therein lies the potential of this platform. Let Rosana Sullivan and others create, watch them excel, and eventually give them the keys to the Porsche for a feature film of their own. Fingers crossed that’s what happens.

Her film Kitbull is about the unlikely friendship between a stray cat (who’s obviously scared and suspicious about any interaction with somebody other than its stuffed elephant) and a mistreated pitbull (who’s recently been chained outside the scrapheap that kitten calls home). The cat sees the dog as a surefire enemy it must vigilantly protect its sparse belongings from. The dog sees the cat as a potential friend with an infectious enthusiasm in its eyes. As the story progresses, however, we see there’s more than meets the eye as far as their emotional and psychological reasoning for thinking the way they do. Under the correct circumstances, they may just end up discovering the companionship they never knew they wanted and the friendship they always craved respectively.

While the short is very cute and gorgeously rendered in soft textures and playful movements thanks to its depictions of both animals in a heightened state of excitement, pet lovers should be warned about its likely ability to prove triggering as a result of obvious abuse inflicted by the dog’s owner. There’s a welcome and well-reasoned message meant to turn the stereotype of all pitbulls being vicious creatures on its head (a notion unfortunately brought to life by horrible owners exactly like the one on-screen), but Sullivan does so by showing the reality of why this breed is so unfairly maligned. It’s crucial to getting these characters where they need to go narratively, but I’d hate for viewers to be blindsided by the trauma inherent to its presence.

B-

Mémorable | France | 12 MINS

Animation allows an artist so much more room to breathe than live action—especially when confronted by issues we can’t see with the naked eye. Bruno Collet’s topic is dementia and his short film Memorable depicts it with a stunning beauty via post-modern styles. As Louis’ (André Wilms) falls further behind reality, his view of the world gradually degrades into visions of melting objects (surrealism), disfigured visages (cubism), and a decrease in detail until he himself becomes smoothed out along the edges (impressionism). He begins as a clay-formed figure meticulously sculpted like his wife Michelle (Dominique Reymond) despite his surroundings losing clarity. She becomes the last thing grounding him before his depleting memory can hold no survivors as life disintegrates into color on its way towards oblivion.

It’s a powerful drama that refuses to pull its punches regardless of whether we know where it must end. Sufferers of dementia can sometimes get by depending on how far along they are, so Collet lets Louis deflect from his fear with jokes and trick others via charisma even though he has no clue who the people he’s tricking are. Michelle is the one who sticks by his side, watching his devolution in real time. She’s the one who sees how each day takes something from him that he’ll sadly never get back. So when it’s time to finally say goodbye—an unavoidable imperative either in death or forgetfulness—the bittersweet sorrow of experiencing a final glimpse of life amidst an uncertain abyss is nothing short of heartbreaking.

A-

Sister | USA | 8 MINS

Looking back on a life growing up with a sister four years the lead’s junior, Siqi Song’s animated short Sister starts off with a wonderful comedic streak. She lets the character’s imagination run away with his memories so that the crying baby who stole his toys can become a giant consuming them with a giggle. There’s the more authentically drawn cause and effect of sibling chaos sometimes confusing a parent into punishing the wrong child and the silly adventures undertaken when both are too young to fully comprehend complex meanings to otherwise simple words. Portrayed with stop-motion felt figures covered in tiny fibers swaying as each frame moves to the next, Song’s medium becomes a character as well once she lets its malleability play a narrative role itself.

As we’ll soon find out, however, this look back into the past isn’t a comedy. The sights, sounds (love the squeak whenever the baby presses her finger into her brother’s face), and narration (by Bingyang Liu) may cause us to laugh, but it’s all a means to disarm us from the difficult truth to come. While you can probably guess what Song’s revelation will be due to her being Chinese (and her penchant for sprinkling visual clues into the background), knowing won’t diminish its impact. It might actually augment the whole instead thanks to an inevitably melancholic vein of emotion entering the picture. Truth and lie flip as remembrance transforms into fantasy. How much does family change us? How much does it affect our identity? In a word: immensely.

B

Documentary

In the Absence | USA | 29 MINS

This is what happens when your government leaders are inept, indifferent, and opportunistic. This is what happens when people are given jobs well above their abilities and thus become expected to make decisions rather than follow them. Not only was everyone holding a seat of power in the South Korean Coast Guard unwilling to act as they reported situations to bosses in the hopes of passing the buck, those paid to be heroes when called upon weren’t experienced enough to fulfill that duty or provided with the correct equipment. So they just watched as a ferry holding close to five hundred civilians (half of which were students) sunk. They assumed someone else made the call to evacuate and looked on as hundreds lost their lives inside.

Director Seung-jun Yi compiles footage of this 2014 tragedy from the rescuers’ recordings, phones and dash cams recovered from the vessel, and audio recordings of conversations that never break from their circuitous loop of needing a camera on scene before doing anything. The captain abandons ship. Kids text their parents that they were told to stay put. And President Park Geun-hye simply sleeps. It’s unfathomable that only one government ship arrived and did nothing. It’s unfathomable that civilian volunteers had to arrive to dive in hopes of finding survivors (and later bodies). It’s criminal that those involved gradually begin to lament the fact they’re going to receive bad PR if they can’t start staging that which they should have completed hours earlier. This should never happen.

But it does. Obviously. And if not for dedicated parents and bystanders refusing to forget (months-long protests were held before a trial inevitably opened), it might have been covered up. Yi’s In the Absence therefore exemplifies the importance of good journalism and the necessity for full transparency in all government activities. These are elected officials filling crucial, life and death positions with under-qualified applicants. They must be held accountable and the public must know the details in order to better understand whom they’re voting for next. It’s one thing to do your best and still fail, but a whole other to watch and do nothing. The latter unfortunately appears to be the norm these days. You don’t have to look much further than Trump’s White House for proof.

B+

Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone (if you’re a girl) | UK | 40 MINS

Even when the Taliban was driven out of Afghanistan, young girls still weren’t guaranteed an education and those from strict families past the age of thirteen were generally not allowed to leave their homes. The reason: a patriarchal sense of “honor.” Parents can’t risk their daughters being kidnapped on their way to school because of how such an act would ruin their reputation. While sons are at university, someone has to earn a living to keep food on the table. Just because the Taliban wasn’t enforcing a burqa law and punishing innocent people for petty transgressions doesn’t mean women stopped being second-class citizens born and bred to be wives and mothers. Thankfully there are some willing to fight that stereotype and help young girls choose their own futures.

While Carol Dysinger’s documentary Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone (If You’re a Girl) focuses upon the educational institution known as Skateistan and its fearless teachers doing everything they can to empower the next generation of women to fight for their rights, I found myself enamored by a couple of the students’ mothers and the strength they show to not force their daughters onto the same path their families forced them. These women know how lucky they are that something like this school exists because it provides them a way out. After all, female illiteracy isn’t an unfortunate byproduct of a cultural divide. It’s the intentional effect of a system built to keep women subservient to the men in charge. Literacy therefore proves a potent weapon of defiance.

The teachers are arming these kids with the tools to survive and hopefully instill change themselves. That’s where skateboarding enters the equation. Just as important as reading, writing, and arithmetic, this sport becomes a way to conquer fears and imbue courage in ways these children can better comprehend in the moment. It’s about getting on that board and not falling off in front of your peers. It’s about excelling at something only boys are allowed to do (at least outdoors) in order to break down the psychological barrier they’re each born with that says they can never be as important as a man. That this bravery also assists in combatting the horrors of enduring the tragedy of suicide bombings every week in Kabul is frankly an added bonus.

Dysinger captures the mental fortitude that results from adults (the student support officer talks about the time she smacked a member of the Taliban in the face after he hit her) and kids alike. The latter is portrayed via multiple ages too as two graduates of the program who now teach skateboarding share their success stories and aspirations while numerous current students are shown laughing, learning, and preparing for whatever might come their way. It’s inspiring to watch because we can understand the difficulties that go into a program that purposefully challenges the status quo. That a little thing like a dedicated school bus to alleviate parents’ worries for kidnapping can get them on-board proves how people will support change if trust is instilled. Things can get better.

B+

Life Overtakes Me | USA | 37 MINS

Directors John Haptas and Kristine Samuelson’s documentary Life Overtakes Me is a call to action. Where many films revolving around ailments seek to provide answers, this one hopes for recognition and subsequent research necessary to find solutions. The reason is simple: nobody knows the underlying truths behind Resignation syndrome. All we know for certain is that it’s real, occurs at an extremely high rate in Sweden, and is growing internationally. The latter comes as no surprise considering our world has been growing more and more insular just as our ability to embrace disparate cultures through an exponential increase in information has arrived. As wars and genocides continue to create refugees at an alarming pace, borders of “free” nations become crowded. How they react proves key to humanity’s survival.

It’s not so great currently as countries rife with anti-immigrant sentiment move towards stricter asylum qualifications. This means that the children of parents threatened with death back home are left in a state of limbo. They’re allowed in, assimilate, and reclaim a sense of safety. That all goes out the window, however, the moment a judge rules that their family’s application to remain permanently has been denied. Some kids grow distant to the point of non-responsiveness. Their fear and dread manufactures an existential crisis that shuts their body down until it reaches a comatose state without any physical cause. Parents must therefore wait months at a time in hopes the situation changes. It isn’t a ploy to force governments’ hands. It’s a psychological effect of Earth’s rising hate.

Haptas and Samuelson portray the home life of three young children afflicted by the syndrome. We hear their parents’ harrowing stories and view evidence of when these kids were healthy and vibrant. Medical experts explain what’s happening to the best of their knowledge, but their lack of ways to stop it sticks with us most—especially since Sweden is no longer the only “safe haven” creating such patients. Older generations enjoy saying that newer ones are weak, but they have no understanding of the unique pressures today’s youth faces. You can’t hide from atrocities anymore now that tragedies occurring a thousand miles away hit home just as potently as those down the block. Kids are currently confronting their mortality earlier than ever before and it’s taking its toll.

B+

St. Louis Superman | USA | 28 MINS

It’s horrible that tragedy is the cause, but seeing and hearing how Bruce Franks Jr. took up the call to government in order to instill the change his community needed to prevent future tragedies is nothing short of inspiring. This is what American government was always supposed to be: citizen leaders fulfilling their civic duty to represent their constituents. It wasn’t about full-time employment or selling off votes to lobbyists. There was supposed to be turnover as each community evolved and grew and therefore needed younger, more familiar voices to speak towards any new developments cropping up as the years went by and demographics shifted. The moment a state official is no longer able to help becomes the moment someone else is called upon to take his/her place.

Sami Khan and Smriti Mundhra’s documentary St. Louis Superman shows one such moment as the murder of Mike Brown. The Black Lives Matter protests that ensued found Franks on the front lines. That’s when he realized just how badly the system built to protect Americans failed those who looked like him. So he ran for office and won (after challenging for a revote in court due to absentee ballot inconsistencies). He presented a bill that could help turn the unnecessary deaths of young children into a health epidemic. And through it all—vigils, funerals, conferences with felons, raising his kids, etc.—he still found the time to get back on the rap battle stage and confront an opponent who argued he’d become part of the system.

How else do you expect change to happen, though? How can that system transform if you aren’t there to remake it in your image? It doesn’t mean that Franks sold out. What he actually did was step up. He recognized his power and the power of the disenfranchised if rallied together to fight for their rights. After enduring so much hardship thanks to first-hand knowledge of St. Louis’ gun violence, he knew something had to give for his children to have a chance at surviving adolescence alive. The film doesn’t pretend it’s an easy road and neither does Franks himself once the pressure of what he’s doing compounds. But his voice is heard. It reverberates throughout his community and opens people’s eyes to the possibilities their futures hold.

A-

Walk Run Cha-Cha | USA | 20 MINS

By the time the Vietnam War was over, the area was officially communist. Because Chipaul Cao’s mother was a successful businesswoman at the time, the government came and demanded she relinquish both her factory and home. That’s when the family knew they had to escape. Maybe there was a risk of failure, capture, or death by leaving, but staying put with nothing (and little chance of improvement) was hardly a better option. The only caveat Chipaul had was the reality that he would need to say goodbye to his girlfriend of six months, Millie. It would be years before his efforts to bring her to America bore fruit and by that time they had to find careers to start a family together. Now at sixty, they’re having fun.

Laura Nix’s documentary Walk Run Cha-Cha presents that fun via dance lessons from renowned choreographers Maksym Kapitanchuk and Elena Krifuks. It’s a cute tale of love and romance finding an outlet through the thing that brought Chipaul and Millie together in the first place. A slow dance connected them and now competitive dance keeps them young despite still working the grind of engineer and auditor respectively. But they’re happy. They have friends, enjoy practicing four nights a week, and put everything into giving the best performance they can when the moment to wow arrives. Past hardships are therefore an afterthought—a catalyst for where they are, but not necessarily who they are. It makes sense then that Nix would gloss over the drama to focus on the joy.

For better or worse, this decision does render the film as feel good fluff. That’s not inherently a bad thing, but it can’t help separating its impact from that of an Oscar-nominated grouping focused on high stakes and harrowing material instead. It’s a nice change of pace in that regard because it allows us to experience a human tale dealing with life rather than death. This is a success story. The Caos prevailed despite tough times and are reaping the benefits of freedom their achievements have afforded them (even if, like most American middle class, they can’t afford to retire). We can relate to their desire to let their love bloom like it couldn’t decades earlier. We admire the life they’ve built and the inextinguishable fire burning within.

B-

Live-Action

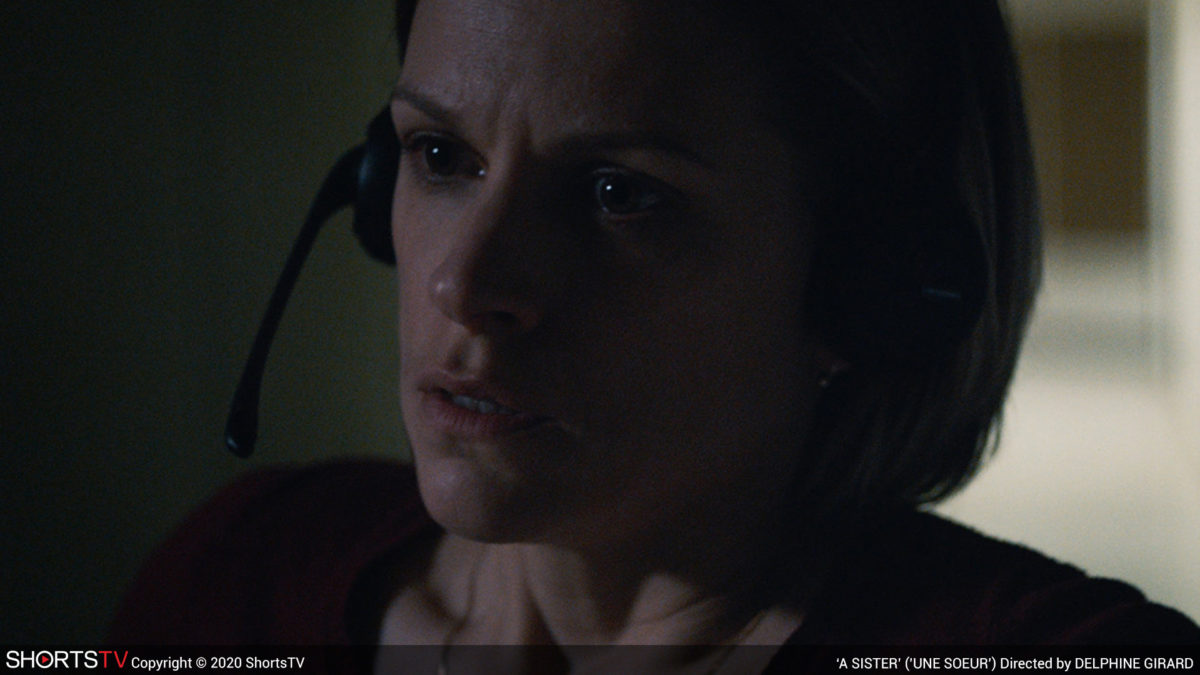

A Sister | Belgium | 16 MINS

A woman (Selma Alaoui’s Alie) is the passenger inside a car heading down a dark road at night. She tells the driver (Guillaume Duhesme’s Dary) that she must call her sister (who is currently babysitting her daughter) after missing multiple messages. It only makes sense then that she’d be worried about the urgency to connect. What we soon discover, however, is that the woman on the other end of the phone isn’t a relative. Alie has actually called emergency services to covertly make an operator (Veerle Baetens) aware of the danger she’s in. Unable to speak in detail with Dary sitting by her side, it’s up to this stranger to ask the right yes or no questions necessary for clarity. One verbal slip could spell tragedy.

The result unfolds with white-knuckle suspense as writer/director Delphine Girard cuts between the interior of Dary’s automobile and the emergency call room. Baetens’ operator is thrust into the role described by the title: A Sister, desperate to ensure Alie doesn’t hang-up only to never be heard from again. For every question asked comes an answer that’s alternately cryptic, irrelevant, or exactly what is needed. With those responses come rapid-paced memories of assault as the victim relives her recent trauma while attempting to remain calm enough for the interaction to seem as innocuous as possible. Sometimes she’s able to and other times she’s not as Dary grows more impatient and erratic. The moment he tells Alie to stop talking is the moment when courage must transcend fear.

It’s a tense ride that could end in life or death depending on how cornered Dary feels. This uncertainty stems from the answers Alie provides. Did he hit you? “No.” Did he push you? “No.” These are questions to which she could have said, “Yes” without repercussion, but she doesn’t because what he did goes beyond the physical. And while Baetens’ character being a woman proves important to the plot, it’s also crucial to the experience itself. Because what might a man have done with those answers? Would he have felt the urgency? Would he have known Dary’s potential for violence was just as meaningful as if he’d already committed it? Girard confronts so many implicit questions with one simple conceit and it’s all the more powerful as a result.

A–

Brotherhood | Tunisia, Canada | 25 MINS

Terrorism is a complex topic too many gloss over in a desire to pretend it’s simple. We generalize and make blanket declarations against an enemy all while refusing to even attempt to understand where they’re coming from. So we of course would never accept the reality that it’s often our own actions that ultimately ignite theirs. It’s why Zionists in Israel label Palestinians terrorists despite being the ones who stole their land. It’s why Americans adopt xenophobic ideologies that lump good people in with bad simply because of the color of their skin, the God they worship, or the language they speak. Just look at the ways in which Republican politicians wish to control women through legislature in the same breathe as they denounce Sharia Law.

This is a product of fear and it occurs on levels much closer to home than war. Think about the domineering visage of a parent punishing his/her child in ways that push them into the arms of someone willing to lend a helping hand in return for loyalty to a cause they’ve conveniently recontextualized for better recruitment results. It’s how cults are created and how families are broken apart. It’s why Malek (Malek Mechergui) escaped what he believed to be a childhood of indentured servitude to fight alongside his ISIS “Muslim brothers” in Syria. And it’s why his father Mohamed (Mohamed Grayaâ) harbors such rage upon the boy’s unannounced return with a new bride (Jasmin Lazid’s Reem). He fears Malek will brainwash his younger brothers too.

Writer/director Meryam Joobeur’s powerful short Brotherhood shows what the distance between Mohamed and Malek will create if they refuse to see each other as anything but enemies. The son saw his father as an oppressor then and the father sees his son as a murderer now. But there are details yet to be spoken and regrets yet to be confronted. Allegiances have been warped by assumptions and the one in the dark towards what’s happening imagines the worst like always. Appearances can be deceiving, though, and actions taken without knowing the full picture can cause permanent damage until a so-called savior discovers he’s become the tyrant he thought he was fighting against. Every hero is another’s villain and their shared silence will only guarantee this cycle continues forever.

A

Nefta Football Club | France | 17 MINS

Two men (Lyès Salem’s Salim and Hichem Mesbah’s Ali) are searching for a mule. Two boys (Eltayef Dhaoui’s Mohamed and Mohamed Ali Ayari’s Abdallah) are on their way to a makeshift desert soccer field to have a match with the friends when they come across the animal standing on the Tunisian/Algerian border. Mohamed doesn’t have time to deal with his little brother’s excitement at finding the surreal scenario that is an abandoned mule listening to music through headphones, but he checks what’s in the bags it carries nonetheless to discover a potential payday beyond his wildest dreams. Suddenly we recognize why Salim is so adamant that Ali not take a rest until they find it. The package they lost could be the difference between life and death.

Writer/director Yves Piat isn’t interested in using Nefta Football Club to tell that story, though. The impulse for a heavily dramatic film full of dangerous threats and sociopathic criminals must have been at the back of his head when imagining this plot, but he decided to lean into the absurdity of the situation instead. Because while Mohamed is old enough to know what he’s found and what he can do with it, Abdallah is not. All this boy wants to do is hang out with his older brother and play soccer in the desolate wasteland that is their hometown. So what would happen if Abdallah got his hands on the goods without Mohamed present to stop him? How does his believing they’re something they’re not impact his actions?

The result is a comedy of errors beautifully shrouded beneath this arid environment of poverty and opportunism. Piat expertly walks a tonal tightrope to ensure things never get goofy enough to dismiss the setting or scary enough to negate the humor born from its inherent severity. So we chuckle when Ali figures out how he misinterpreted Salim’s instructions because the joke is effectively written as an enjoyable miscommunication they can grin about in hindsight if the pain of its present cost evaporates. And we can smile in astonishment alongside Mohamed’s shock when he realizes what’s happened to his best-laid plans. Piat reminds us via the amusing fickleness of fate that kids should be able to remain kids much longer than today’s broken, war-torn world currently allows.

B+

Saria | USA | 23 MINS

Tragedy struck the Guatemalan orphanage Virgen de La Asuncion Safe Home in March of 2017 as forty-one teenage girls perished as a result of a preventable situation. Some survived to tell their side of the story: the rampant physical and sexual abuse by their custodians, the protests and attempted escape leading to their quarantine, and the possibilities of how the fire that killed their compatriots began. Writer/director Bryan Buckley has taken these accounts and the establishment’s history to weave a gritty drama out of the nightmare that is life for young girls held as second-class citizens by authority. He creates two sisters at its center to serve as hope and catalyst. Ximenia’s (Gabriela Ramírez) love supplies the former while Safia’s (Estefanía Tellez) rage positions her as the latter.

Not believing the events themselves were enough to win our attention, however, Buckley takes Saria down a melodramatic road of manipulation by using his leads as vessels with which to tug at heartstrings even further than mere murder. I get the reasoning behind this maneuver, but I can’t help seeing it as a disingenuous one that belittles the heinous crime being committed. It shouldn’t matter whether these girls were innocent orphan bystanders or guilty felons serving time as juvenile delinquents. This idea that we need them to wonder about the future and long for romance makes it seem as though we as an audience are unwilling to care about them without them being beyond reproach. We shouldn’t be implicitly conditioned to pick and choose who deserves our sympathy.

I’m not saying this is Buckley’s intention, but it’s what occurs when the runtime is too short to give its content the space for authenticity. The film tries too hard to provide information already present without hitting us over the head. We feel for what’s happening on a purely human level regardless of whether a boy (Jorge Ávila’s Appo) is involved as a means to prove to Saria that not all men are monsters (a warranted belief considering what the men at this orphanage are doing to her). That she’ll never have a romance of her own is tragic, but it’s not more so by spelling it out. Dead people can’t have a lot of things. It’s as though her demise takes a backseat to the film’s ambitions.

C

The Neighbors’ Window | USA | 20 MINS

Everyone wants for more and often for that which they cannot have. That’s when our desire grows largest because we remember what was, regret what wasn’t, and lament how that which we have might never be enough. This goes beyond careers or finances or location. I’m talking about love, family, and joy. Is that a silly thought to have when you’re married with three kids and comfortably situated within a life together that you built with intent and purpose? Sure. But it’s also very human because contentment breeds fantasy. What we have becomes rote to the point where a distraction is necessary to cope. What if we were single? What if we didn’t have children? What if we were more attractive? Where did our lust go?

These are the questions facing Alli (Maria Dizzia) and Jacob (Greg Keller) in Marshall Curry’s The Neighbors’ Window. And they’re natural questions to ask within a societal infrastructure hinged upon success and growth. The moment you find yourself digging in, complacency rears its head and achievement quickly turns to failure. We don’t allow ourselves to be comfortable when our minds tell us that comfort can always be improved. So when Alli and Jacob discover the young couple across the street stripping naked to have sex in front of drape-less windows, they can’t help but wish it were a mirror instead. They (Juliana Canfield and Bret Lada) don’t have screaming children, puke-stained clothes, or deteriorating bodies. They remind this couple about the divine gift that is youth.

Does that mean age isn’t, though? Does that mean someone couldn’t be looking through Alli and Jacob’s window with the same awe at what it is to be happily married with a family? This is the bane of privilege: an inability to see how good you have it compared to others because all you’re willing to see is what you lack. When the status quo is health, security, and happiness, those accomplishments become rendered as your new bottom. Alli and Jacob are therefore wondering how they could add these strangers’ capacity for sex, adventure, and independence to what they already have rather than acknowledging how reality often demands a trade off instead. All they know for sure is what they see and surfaces can hide so, so much.

Curry’s heavy-handed narrative propulsion to reveal this truth hits us hard emotionally regardless of it proving conveniently tragic and blatantly manipulative. The moment the cracks in Canfield and Keller’s lives arrive, we know what’s coming even if Alli can’t see the reckoning in store. That too is an example of her privilege and perhaps naiveté where her ability to escape youth is concerned. Because she survived her own to find love and motherhood doesn’t mean everyone else will. She can’t imagine what’s about to befall that other apartment because she has no internal reference point. It’s easy to thus imagine changing places when a future similar to hers is the guaranteed bare minimum. But it’s not. What Alli has is actually a future too many will never see.

B-

The Oscar Nominated Shorts open in NY and LA on January 29 before getting a limited theatrical release starting January 31. See the official site for more details.