Wild Indian is a bold, anger-wreaked character study, creating a deeply unsympathetic antihero who nevertheless inspires some pity and understanding. Although representation for indigenous American people in the arts is increasing, it’s still hard to recall a film quite like Lyle Mitchell Corbine Jr.’s debut, which moves its Native American characters from a cinematic periphery they’re most often found towards the center. Its story of an upwardly mobile Ojibwe man (Michael Greyeyes), haunted by a past crime, surprises us, its progression almost like an old-fashioned morality tale, and Corbine feels no pressure to skew to politically correct positive representations.

Many debut films proceed as if the director believes they will never make another one; any idea is fair game for inclusion. Wild Indian embodies this––but in the best possible sense. It shows a real mastery and confidence in achieving a certain cinematic language: a pre-title prologue sets up a slow tracking-shot-laden Malick-like tone, which gives the impression the film will remain in this register. But this is one fake-out among many in this structurally slippery work, which then settles into a comfortable amalgam of stark Greek Tragedy, Biblical allegory, and film noir.

If a contemporary film has child and adult versions of the same character, the expectation is that these timelines with dovetail in flashbacks. Here, Wild Indian takes its first bold cue from theatrical works like Oedipus Rex and the Oresteia, tracking fatalistic cycles of violence in resolute chronological order, and of course ending, bloodily and perversely, in the Katharsis coined by Aristotle in his Poetics. Drawing comparisons seems relevant, because Corbine is operating in uncharted territory, in a realm where Native American filmmakers thus far have been prevented from telling stories in their own voice. His eclectic influences therefore allow him to create a precedent or aesthetic from the ground up.

He finds equal darkness and pessimism in both narrative timelines: the fuggy mountainous climes of northern Wisconsin, and the beige-coloured Northern Californian affluence he and cinematographer Eli Born depict with imposing sterility. Makwa (Phoenix Wilson as an adolescent), and Ted-O (Julian Gopal, likewise) are cousins living in working-class families in the aforementioned area of the midwest. They have a grin-and-bear-it attitude to eking ahead, supporting one another as their respective families drown in alcoholism and domestic violence. In a nightmarish woodland sequence, a conflict with a third Native American teenager prompts a fatality which the boys decide to cover up, and their adult paths diverge with wildly differing fortunes.

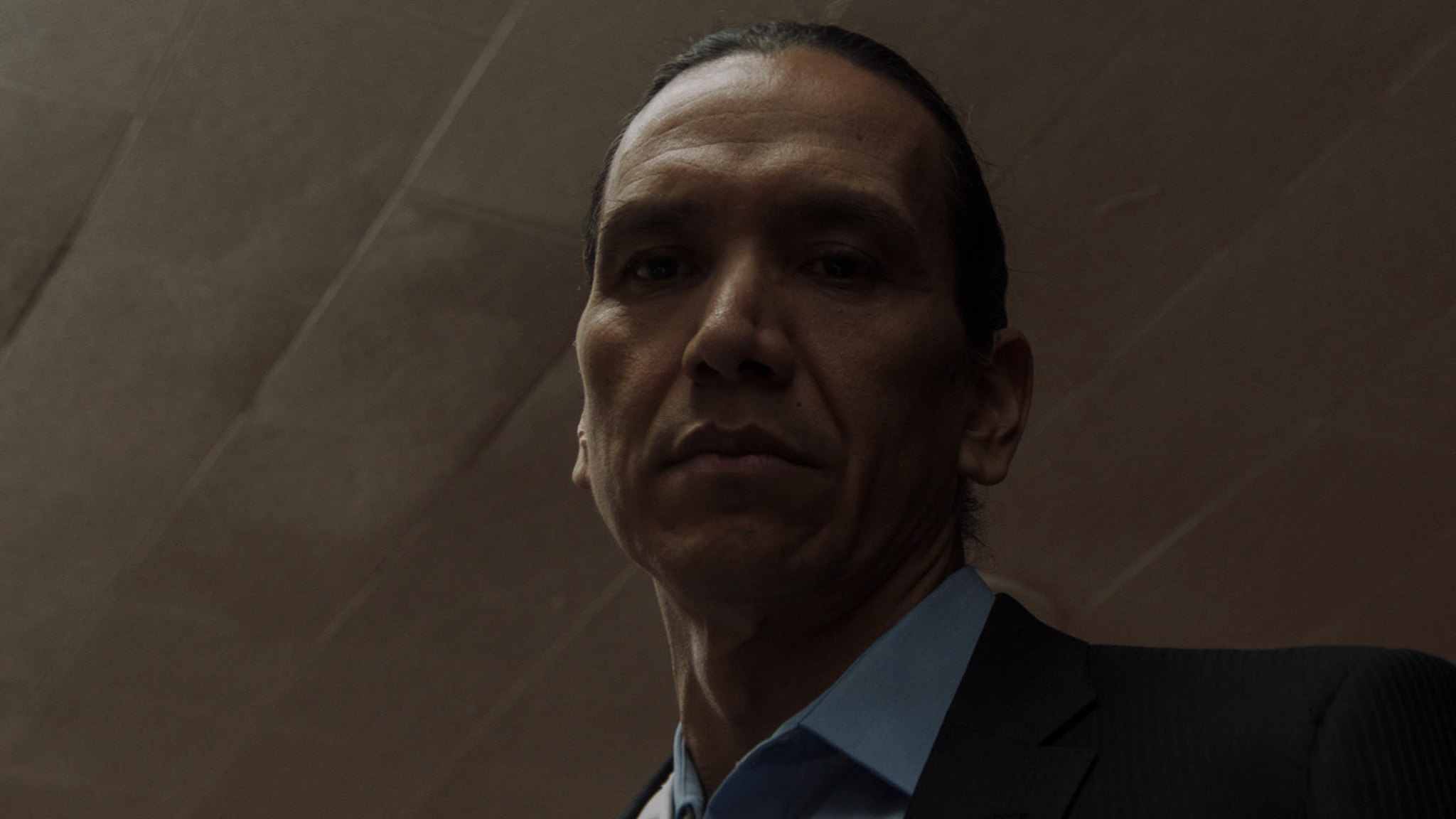

Akin to Moonlight in how a conclusive meeting between the dual protagonists is set up, yet Corbine has an original, if disturbing, method of frustrating this outcome. In a high-ranking corporate job, Makwa now goes as the affluent Michael (Greyeyes), wedded to the beautiful Greta (Kate Bosworth), hiding his psychological damage deep beneath an inviting, white-collar facade. Adult Ted-O (Chaske Spencer) is a habitual offender with multiple prison stints on his rap sheet, although not for violent crimes. After reuniting with his beloved older sister in tender fashion, he hitches up for Michael’s residence with ambiguous intentions in tow.

There’s something very candid in the way Corbine brings the pain of an archetypal modern Native American existence to light. He wrote Wild Indian after returning home to his reservation after a year in Berkeley, California, nursing feelings of disconnection to his heritage. It asks open questions about the place of indigenous people in modern-day America without coercively batting around solutions, and isn’t shy about invoking the community’s issues with poverty, drug abuse, and suicide. Whereas in a film like Wind River, this had a judgemental overtone, here it’s frank and scrupulous, and Makwa’s own propensity towards violence speaks of greater depths of inner violence and inherited self-loathing than we could possibly imagine.

Wild Indian premiered at Sundance Film Festival.