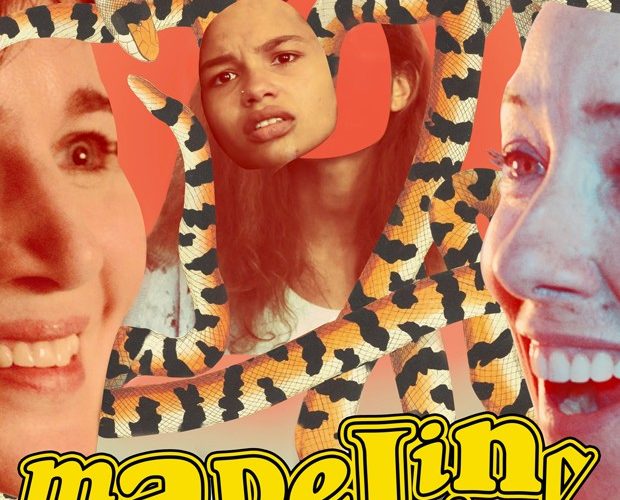

While many breakthrough directors achieve such a status by helming one feature, Josephine Decker achieved acclaim with two films, Thou Wast Mild and Lovely and Butter on the Latch, which received theatrical releases simultaneously in 2014. Marking her return to narrative feature filmmaking at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, Madeline’s Madeline is a drama of boundless spontaneity as Decker deftly examines mental illness and the potentially exploitative lines a performer may cross when pulling life into art.

Decker places us in the shifting psychological headspace of Madeline (Helena Howard, in an incredibly assured, emotionally bare breakthrough performance) as she navigates her overprotective mother Regina (Miranda July) and a layered relationship with her theater director Evangeline (Molly Parker). Eschewing exposition and reserving characterial context for later in the film–such as Madeline’s past struggle with mental illness and her family background–Decker instead disorients the viewer in alluring fashion as we’re whisked between glimpses of her life at home, theater practice, and in her imagination. The playful nature of this first act–for example, embodying a turtle on the stage, then in a single cut, we see one at sea–can feel repetitive in its commentary on performance, but it does set the impressionistic groundwork for Decker’s film quickly gets much stranger, more personal, and thrillingly unpredictable.

Continuing to stay in Madeline’s perspective, the knotty triangle of expectations and control between herself, her theater director and her mother grows more intricate and convoluted to great effect. Moving a mile a minute, Decker explores a mother’s obsession for her child’s safety while Evangeline is testing those very boundaries as they rehearse for their performance. Inch by inch, Evangeline, with all of her outward niceties, asks more from Madeline, desiring her traumatic story to be the foundation of their theater troupe’s new performance so she can vicariously produce a work of powerful art. While we never explicitly know if what’s she doing is for personal or performative means, Madeline oversteps boundaries as she meets Evangeline’s family, including hitting on her husband. Meanwhile, Regina, knowing Madeline’s past struggles with mental illness and the damaging fall-out, balances the over-bearing protection of her child and genuine love until her path reaches a more intrusive place.

Shot by cinematographer Ashley Connor (who also has The Miseducation of Cameron Post at the festival), there’s a warm vivacity to the palette and an unexpected verve, as if one could never guess what the next shot will be, including experimental Punch-Drunk Love-esque color abstraction to a wholly enveloping finale that moves with the startling boldness of mother!’s third act. To further place us Madeline’s head space, the sound design accentuates her heavy breathing through fraught sequences of conflict and performance, which, in this film, are rendered one in the same.

The greatest praise I can give Madeline’s Madeline is that, considering its sheer momentum and imaginative tackling of the complicated issue of exploitation for art’s sake, multiple viewings would reap greater rewards. With just one, it’s clear Decker has crafted a whirlwind of an experience, one that coheres in breathtaking bravado by the climax when art as therapy reaches its uncomfortable, astounding conclusion. There will never be easy answers when dealing with the soul-baring act of producing truly great art, but Josephine Decker’s film is as mesmerizing a plunge into the process as one is likely to find in modern cinema.

Madeline’s Madeline premiered at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival.