Not knowing is the point. At least that’s what writer/director Simon Lavoie says in his director’s notes for Nulle trace [No Trace]. He’s not looking to create a film with narrative propulsion or mainstream appeal within an industry he’s actively seeking to rebel against. He instead wants to go back to the art by engaging audiences with form, sensory input, and ideas. Lavoie’s goal is to therefore embrace an unspoken “pact” with viewers that allows for a benefit of the doubt where understanding and intent are concerned. What we take from the film is thus more about what we’re bringing to the experience than what he has provided for it. Setting and time are rendered inconsequential as meaning takes centerstage. Its purpose and success are ours to give.

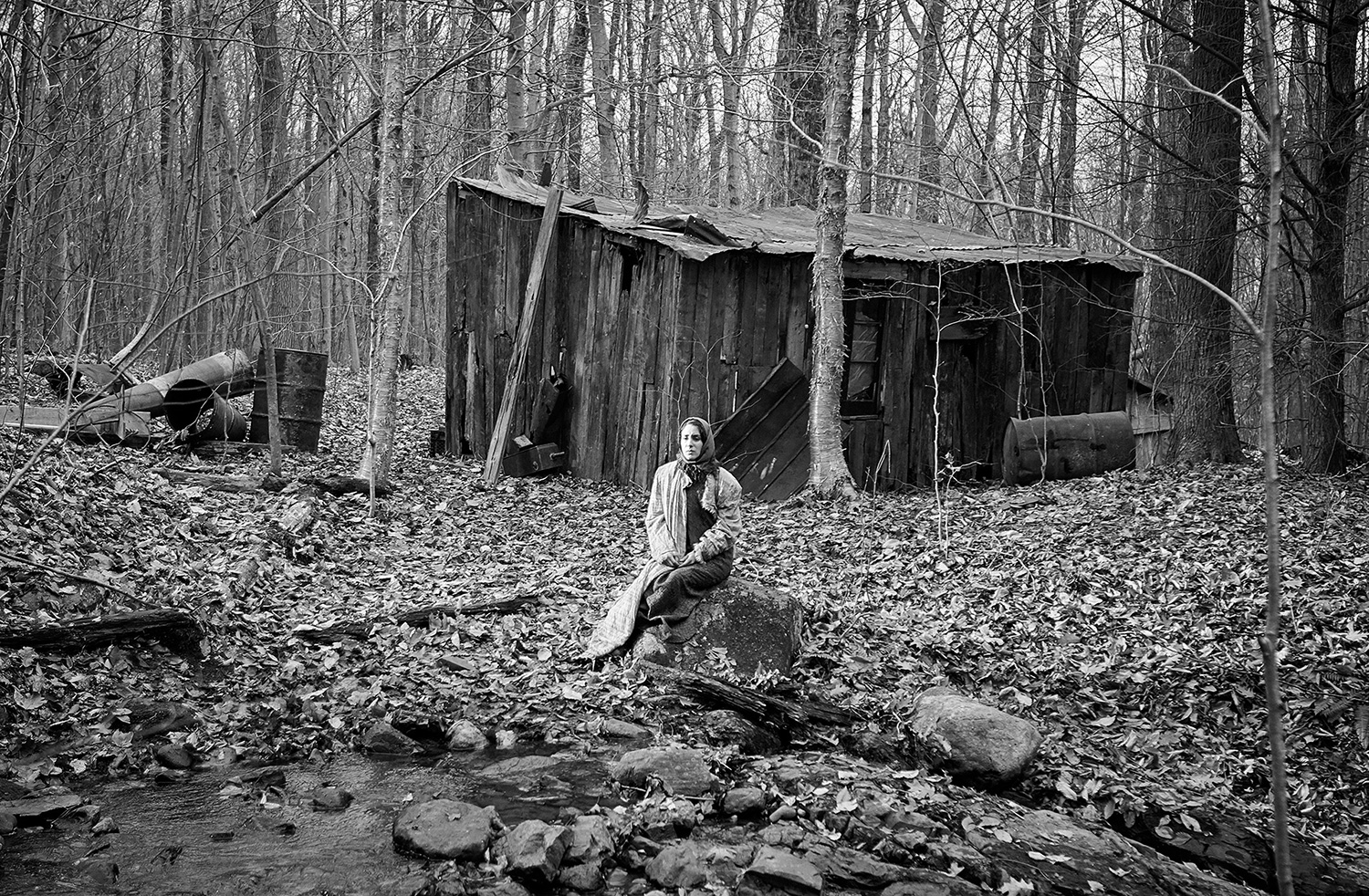

There’s beauty and frustration in this truth depending on how you enter this pact. Those looking for a linear story and context will be sorely disappointed while those willing to let themselves be absorbed by its world won’t. Because while Lavoie eschews exposition for mood, we nevertheless do become familiar with the environment drawn. It’s militaristically oppressive with border check-stops and universal fear. It’s quietly violent with everyone clinging to a handgun thanks to mistrust proving a universal trait towards survival. And whether you’re of N’s (Monique Gosselin) ilk or Awa’s (Nathalie Doummar), you might even feel a tug of hope beneath the palpable air of despair permeating every frame. Where the former has hardened herself to the present, the latter still believes in a future.

The difference ultimately lies with faith. N is an atheist with good reason considering the arduous life she’s carved out of the ruthless darkness as a smuggler across territorial boundaries. Awa is a devout Muslim praying each day for Allah’s benevolence to guide her and her child to the safe arms of her husband. N’s pragmatism has surely kept breath in her lungs more than once while the naivete born from Awa’s blind allegiance to finding grace within nightmare has surely left her on avoidable pathways towards danger. That they come together here can therefore be dismissed as the product of convenience on behalf of Lavoie or destiny on behalf of the characters. Either way you choose, however, that which one woman possesses might just save the other.

Lavoie’s spare environment is primed to let this be true. With little dialogue and a constant shifting of aspect ratios from full frame to widescreen (often with subsequent cuts regardless of whether the scene has changed), we’re privy to the stark reality that these women face with harrowing images of charred and bloated corpses centered within. How will N shield Awa from these gruesome images once they cross paths again days after the former helped get the latter out of what we can only assume was a more intolerant state than the next? How will Awa be able to trust N when she’s the only person besides her husband that knew where she’d gone? Can N’s instincts keep them alive? Will Awa’s faith open her heart?

Beyond even that, however, is what their beliefs mean in the grand scheme of things. No Trace inevitably takes a spiritual turn by its end wherein what we’ve seen isn’t necessarily what is. You can reconcile this fact with the ways in which atheists and the faithful differ on the subject of death. Where one sees this life as but a test to endure before finding peace in paradise, the other looks upon what they have now as all they’re ever going to get. N is thus desperate to keep going even though her pursuit to live is devoid of any opportunity for happiness. Awa is conversely confident that the horrors she experienced are but one part of a journey her family will soon set right.

Does N’s practicality trump Awa’s delusions? It does if you’re N. Awa doesn’t believe what she knows is coming is a delusion. Her faith renders it as a certainty until proven otherwise. And even if those truths are proven wrong superficially, that doesn’t mean they’re endgame won’t still be proven correct along some different road. Because what is death to her but a doorway towards a new life? Where N sees those corpses as a definitive ending, Awa might just interpret them as a new beginning instead. One can never be away from those they love if death isn’t held as something to fear. While Awa fears the pain she’s been forced to endure at the hands of animals, she doesn’t fear the possibility that they’ll kill her.

So as things get direr thanks to the changing seasons and dwindling food supply (where it comes from with coded numbers is one more mystery we’ll never know because we don’t need to know it), this chasm between them grows. N prepares for flight while Awa prepares to be saved. Lavoie has manufactured a struggle pitting pessimism against optimism in a way that may actually negate everything he’s put on-screen. By showing us what pessimism demands via N’s vantage point (happy endings are for suckers), the audience suddenly becomes that which is made blind. We know what she sees only because that’s what Lavoie is showing us. He’s using mainstream cinema’s conditioning to lead us down a path that’s really just as flimsy as the other.

Because what if N isn’t the story’s focus? What if Awa is? What if the journey on-screen is one where the latter’s victim of heinous abuse is supposed to save the former despite the fact that she doesn’t think she needs to be saved? The result blurs lines so the physical and spiritual can co-exist. Rather than keep N vigilant, that which she sees may actually be steering her into a trap. And rather than leave Awa vulnerable to attack, that which she believes (despite all signs to the contrary) may prove their chance to escape. Death is thus an illusion—nothing more than an event imbued by whatever importance you bestow upon it. You either fear its finality or embrace the wonder in its potential.

No Trace is playing as part of the 2021 Slamdance Film Festival.