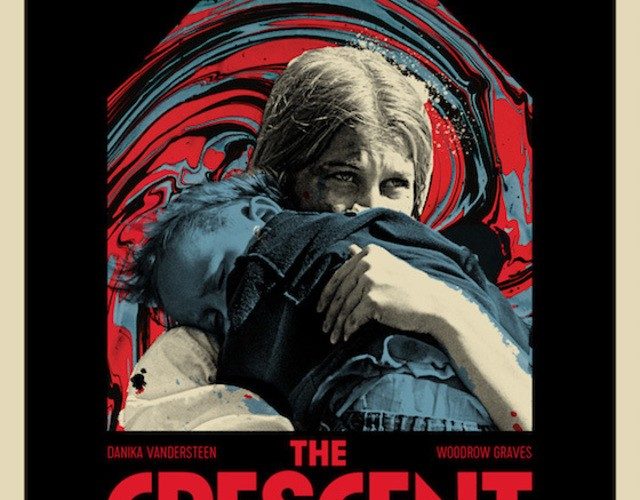

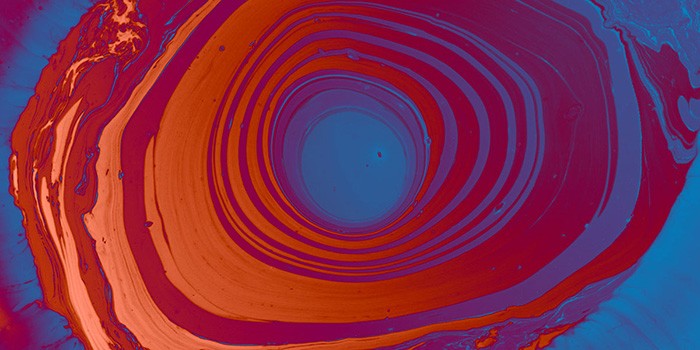

It starts by enveloping us in marbleizing paint — overlapping colors raked to warp dots into abstract patterns — and the loud aural pulses of a musical soundscape as heavy and permanent as those oils are fluidly malleable. We assume it’s merely a sensory aesthetic Seth A. Smith constructs to provide the tone for the subtle horrors still on the horizon, but don’t be surprised if you begin to interpret each new artwork as a self-portrait of characters we’ve yet to meet. Treat them as mood rings simultaneously displaying the strength of will and love to keep each hue from merging into muddy brown and the vulnerability of time folding in on itself like each layer of curved lines. They’re products of Beth’s (Danika Vandersteen) turmoil, a fight intentionally misconstrued.

Smith presents this overload of vision and sound as a contrast to the somberly quiet drama that begins once The Crescent‘s opening credits end. He and screenwriter Darcy Spidle place us in that intense headspace to purposefully disorient and dare us to decipher its puzzle while the plot itself seems shallow by comparison. The former’s power propels the latter’s narrative, a tempest of emotion and grief pent up inside Beth’s soul as she attempts to deal with the death of her husband Peter (Andrew Gillis). I’ll be the first to say that this initial act is slow and methodical. They lack the impact of those abstractions as they introduce the trying, isolating dynamic between mother (Beth) and son (Woodrow Graves’ Lowen). They mask their pain.

So it can get frustrating as Beth fends off depression while Lowen craves her unyielding attention. These scenes are mostly unrehearsed events placing a first-time actress opposite a two-year old (Smith and producer Nancy Urich’s real-life son) to interact as humans would with peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, toy cars, or pails of sand. The monotony provides them a desire to step back and seek freedom just as doing so opens the door to potential tragedy and a mixture of guilt and elation in the aftermath. Beth merely seeks an escape, this retreat to her mother’s (Andrea Kenyon) old house on a Nova Scotia bay a means to gather her thoughts. And as a young mother now widowed, it also allows room to become the parent Lowen needs.

As soon as I started feeling disconnected from the narrative, however, Smith revealed new moments of unease that jolted me back to attention. It was the appearance of an impossible cat we’ve heard Beth use as an equivalent to her husband as far as teaching Lowen about death’s permanence, the pet coaxing the boy towards danger with nothing but a silent gaze. It was the arrival of a neighbor (Terrance Murray’s Joseph) with deep voice and chilling smile that sent shivers down my spine, his familiarity and desire to take Lowen swimming cause for any parent to scoop up his/her child and return home. From these tense examples follow words of nightmarish thought — of people long dead yearning for life anew as the living desperately seek those gone.

Talk about “the dead” is Sam’s (Britt Loder), a young neighborhood girl who comes to Beth’s crescent of land to pick through garbage and see what treasures she might find. She becomes a symbol of good opposite Joseph’s evil, hope opposite dread. But we have to wonder which will win out as Beth’s depression takes hold and Lowen is left alone more and more. Waking dreams begin and glimpses outside reveal more and more people waiting, watching. Our handle on what’s real and what isn’t becomes nonexistent as vignettes with changing aspect ratios (mostly tiny squares or portrait rectangles reminiscent of your smart phone’s screen) appear with what could be memories, fantasies, or the voyeuristic gaze of an unseen force. Beth’s internal war manifests externally through the sea.

And as the paint flows, so too does a watery filter over everything. What was a straightforward narrative that risked boredom in its vérité aesthetics transforms into a visually experimental descent towards a new hell — or perhaps an old one. Like the final two seasons of The Leftovers, Smith reveals this notion that loss is experienced on both sides of tragedy. He’s created dueling worlds barely able to discern from each other which is truly “real,” who is dead, or who remains alive. Beth’s marbleized works start to fill the screen again as though a viscous curtain between these two dimensions of existence, Smith’s film suddenly proving unable to stay in one for very long as the other wrests control. Past, present, life, and death exist all at once.

The shift is abrupt, strange, and absolutely mesmerizing as Smith plays with texture, composition, visual artifacts, and genre tropes. We think he’s going to give us a concrete answer by showing what happened the day Peter died, but doing so would be too easy. The Crescent isn’t so banally linear in its use of time or place and his collage of widescreen shots at the house and intimate crops of memory flicker faster until we understand what — if anything — occurs on our true plane of reality. More than grief is a war for survival. More than dark specters of foreboding death are parasitic creatures searching for a way back from the void of nothingness that consumed them. The water is therefore a beginning and end depending on perspective.

What Smith and company have created won’t be for everyone either because of its avant-garde visual styles or its complex narrative construction hidden beneath its surface of everyday interactions tempered by quick interjections of fear. It’s an art film at its core, one that’s unafraid to alienate audiences in order to portray what it must via unorthodox ways. Its art captures Beth’s art, both revealed to be a visual representation and outlet for authentic feelings of loss, perseverance, and hope. Its demons are as much physical representations of one’s futility as they are lingering ghosts of a past yet closed. There’s a reason Beth’s mother suggests she take Lowen to that house and it isn’t to forget or escape. Only there can they maybe return home.

The Crescent premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival.